Balkrishna Doshi, one of the most thoughtful and original architects of his generation and creator of a string of highly admired community and educational buildings in India, has died, aged 95.

In 2018, Doshi became the first Indian architect to win the Pritzker Prize, and in 2022 he received the Royal Gold Medal of the Royal institute of British Architecture (RIBA), in London. These awards, the most valued in his profession, marked Doshi’s contribution to the building of independent India’s institutions over seven decades, and the international esteem in which he was held as a champion of low-cost housing and people-centred architecture; as an inspired educator of architects and planners; and for the global vision he developed as a collaborator with the Swiss master Le Corbusier, with the great US modernist Louis Kahn and with many of Japan’s finest late 20th-century architects.

Amdavad ni Gufa (completed 1995), Ahmedabad, an underground gallery created by Doshi and the artist MF Husain Courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation (VSF)

Doshi also collaborated with leading Indian artists, notably with M.F. Husain on Amdavad ni Gufa (completed 1995), a project for a gallery in Ahmedabad—Doshi’s home city in Gujarat, western India—which developed into a remarkable community-focused permanent installation of Husain’s work, semi-submerged, with interlocking tortoise-like domes and a colour-infused cave-like interior, held up by Stonehenge-inspired tree trunks.

Doshi’s own fine art practice—which Le Corbusier had encouraged in Paris in 1951-54, with his emphasis on sketching as a vital part of his young assistants’ professional education—has come to the fore in recent years. Doshi’s work has featured at global art fairs including Art Basel 2022—The Labyrinth of Dreams, a show of his surrealist drawings, paintings and sculptures—Frieze London 2022 and, at the time of Doshi’s death, at India Art Fair 2023, in New Delhi. Roshini Vadehra, director of the Vadehra Gallery, in New Delhi, told The Art Newspaper that the gallery is working on a monograph of Doshi’s fine art, featuring an interview with Doshi conducted by Hans Ulrich Obrist, artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries, London.

Two aspects of Doshi’s architecture stand out: his focus on low-cost housing and his organic approach to institutional or educational campuses, symbiotically adapted to the Indian climate and ecology.

Doshi’s Aranya Low Cost Housing scheme in Indore (completed 1989) Courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation (VSF)

His work on housing schemes for low-income families is typified by Life Insurance Company Housing, Ahmedabad (completed 1978)—a group of several hundred homes arranged in 54 units, on a duplex model, to encourage the mixing of people from different income brackets—and Aranya Low Cost Housing, in Indore, central India (completed 1989 and subsequently awarded the Aga Khan Award for Architecture), where low-income families were offered core elements to adapt to suit their needs. Giving families this freedom, Doshi said, taught him how a community works together.

Doshi’s approach to campus-planning focused on engagement with climate, with vegetation and spaces for human interaction. It reached its apogee, with a synthesis of international modern and local styles, at the Indian Institution of Management (IIM) at Bangalore (completed 1983). The project shows his close familiarity with Fatehpur Sikri—the supremely refined 16th-century Mughal capital near Agra, with its terraces, halls and pavilions—and the personal influence of both Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn: in particular Kahn’s designs for IIM Ahmedabad (1962-74), where Doshi was associate architect, and where they took teaching out of the classroom and into the campus’s plaza and hallways.

Doshi’s Indian Institution of Management (IIM), Bangalore (completed 1983) Courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation (VSF)

Doshi’s Indian Institution of Management (IIM), Bangalore (completed 1983) Courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation (VSF)

In 2021, the New York Times rated Doshi’s IIM Bangalore as one of the “25 Most Significant Works of Postwar Architecture”, and the critic Nikil Saval described it then as “one of the best instances of a modern architect deferring to the landscape and to the culture of a city, as well as to indigenous architectural traditions.”

Childhood in a multi-generational household

Balkrishna “BV” Doshi grew up in the city of Pune, 100 miles inland from Mumbai, in a bustling household, sometimes 15 strong—”there were widowers, middle-aged parents, newlyweds and adolescents”, he wrote in his autobiography Paths Uncharted (2019). His mother had died soon after his birth and his father, who was 75 at the time of Doshi’s birth, was often absent, busy with his family furniture business and religious and social work. In Paths Uncharted, Doshi writes that he suspects that the absence of maternal love and the ”desire to rediscover this intimacy gave rise to my habit of scribbling whatever came to my mind, right from a very young age”. These scribbles were the beginnings of his life as an architect and fine artist, who drew and painted all his life.

Doshi’s conceptual sketch for an interior at Premabhai Hall, in Ahmedabad, c1956 Courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation (VSF)

Being frugal was “second nature” to Doshi: by family tradition and through the personal example of Mahatma Gandhi. “Being frugal and forgoing is the way I have lived all my life,” he writes in Paths Uncharted. “Frugal habits have allowed me to choose what I want to do because my needs are minimal.”

The first, dramatic, demonstration of choosing what he wanted to do, was to give up his studies at the JJ School in Mumbai and move to London in 1950, to complete his diploma in architecture at the RIBA in London. There he gloried in the institute’s library, something that he recalled fondly when winning the RIBA’s Gold Medal 70 years later. But he gave up the RIBA when he met Germán Samper, a Colombian architect three years his senior—who later designed the spectacular Museum of Gold in Bogota (1963-68)—who encouraged him to come to work in Paris in 1951 in Le Corbusier’s studio, where Samper was assisting Le Corbusier with his city plan for Bogotà. There Doshi learnt his trade, working on the great Swiss-born architect’s Indian commissions, for Chandigarh—a complete new city, where Doshi worked as a senior project architect—and Ahmedabad, where he settled to oversee Le Corbusier’s projects on site.

Doshi’s Institute of Indology, Ahmedabad (completed 1962) Courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation (VSF)

Doshi set up his own practice in 1956 in Ahmedabad, where architects from overseas arrived on pilgrimage to admire “Corb’s” latest work. These included Kenzo Tange, one of the creators of modern Tokyo, who came in 1957 with the structural engineer Yoshikatsu Tsuboi. Tange and Tsuboi talked to Doshi about the stadium they were designing for the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo. Doshi, who was working on his first big solo commission, for Premabhai Hall arts centre in Old Ahmedabad, subsequently went to Tokyo for four months to finalise the design and structural drawings for that project with Tsuboi. The influence of Tange’s contemporaneous work—the Kagawa Prefectural Government Office (completed 1958) and Kurashiki Town Hall (completed 1960)—is detectable in Doshi’s Institute of Indology in Ahmedabad (completed 1962), a pavilion raised on a plinth and designed to house historic manuscripts.

Balkrishna Doshi, sketch for Institute of Indology in Ahmedabad (completed 1962) Courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation (VSF)

In 1958, after his working sojourn in Japan, Doshi continued his globe-trotting education, with a visit to Taliesin West, the studio of the grand old man of world architecture, Frank Lloyd Wright. And then, while lecturing in the United States in 1961, he met Louis Kahn, the modernist magus of Philadelphia, who had recently been commissioned to design a new National Assembly Building (1961-82) in Dhaka, East Pakistan (Bangladesh from 1971). Doshi invited Kahn to apply—in the form of a letter to Doshi himself—to design the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad, which Kahn duly executed to great acclaim with Kahn making annual visits to the site, until his untimely death in 1974. Kahn became, after Le Corbusier, the second great architectural guru in Doshi’s life. They taught him as much of the Classical past, as of the present. Doshi said that he would never have known the work of the 16th-century master Andrea Palladio, and his seminal publications on architecture, but for his two modernist gurus.

Doshi’s CEPT University, Ahmedabad, developed in stages over 46 years (1966-2012) Courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation (VSF)

Doshi’s CEPT University, Ahmedabad (1966-2012) Courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation (VSF)

In his acceptance speech for the Pritzker Prize, Doshi paid tribute to the personal guidance he had received from Le Corbusier. “I was raw enough to be taught by him,” he said. Le Corbusier had told Doshi to live a “disciplined life of exactitude” and to “draw constantly”. “His explaining and drawing taught me about structure, space and light,” Doshi said. “While he was in Chandigarh he would draw animals and people, go to temples and [he] learnt structure from cattle and buffalo … He said you must have a pact with nature.”

An educator and perpetual student

Late in life, Doshi described himself as a perpetual student, and he had longed since proved himself to be an inspired teacher. In 1966 he founded, and designed, the school of architecture at the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology (now CEPT University), Ahmedabad, where he taught for 45 years. The campus grew over the next 45 years, starting with the School of Architecture, before adding a school of planning (1970), a visual arts centre, schools of building science and interior design and finally (in 2012) an exhibition gallery. “CEPT campus has become at once a small campus and a big house,” Doshi said in 2018. His aim, he said, was to escape the shadow of Western schools. “We wanted to find our own identity.”

Sangath, the studio Doshi built for his architectural practice in Ahmedabad (completed 1981) Courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation (VSF)

In 1981, Doshi finished work on Sangath, in Ahmedabad, a new home for his growing practice, whose name means “moving together”. He wanted it to be a studio “that denies what an office should be”. One where the requirements for ventilation demanded the spatial openness and fluidity that he brought to his finest campus work. One of his inspirations for creating this collective approach, this working together, was a sculptor’s studio he had encountered in Egypt, by the pyramids at Giza, which housed a craft centre, a pottery studio and a carpet-making area.

Doshi’s Kamala House, Ahmedabad (completed 1963) Courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation (VSF)

If Sangath, and Kamala House (completed 1963)—the home he built for his family in Ahmedabad, named after his wife—are his most personal projects, the one that best characterises his questing, collaborative approach to his craft is Amdavad ni Gufa, the underground gallery he built with MF Husain. Its creation stemmed from a 30-year-long conversation between the two men about response to climate and the benefits of underground spaces. It was “designed as an art gallery”, Doshi wrote in 2018, but was “transformed and became a living organism and sociocultural centre due to its unusual combination of computer-aided design, use of mobile ferro-cement forms and craftsmanship by local crafts people using [their hands and] waste products.” Doshi was delighted when it became a civic space. Where children and old people felt at home. “I was trying,” Doshi said, “to create delight.”

Doshi and the artist MF Husain observing construction of Amdavad ni Gufa (completed 1995), the culmination of their 30-year conversation about climate and underground spaces Courtesy of Vastushilpa Foundation (VSF)

Monographs, retrospectives and prizes

In 2014, Celebrating Habitat: The Real, the Virtual and the Imaginary and Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People was staged as a retrospective at the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi. Surveys of Doshi’s architectural work were published in 1998 and 2019, the latter to accompany a three-year touring retrospective, Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People. That exhibition opened at the Vitra Design Museum, in Weil am Rhein, Germany, in 2019, and travelled to Austria and the United States—where it was shown at Wrightwood 659, Chicago, a converted apartment building designed by his fellow Pritzker laureate the Japanese architect Tadao Ando—before concluding at Genk in Belgium in November 2022.

In his nineties, Doshi remained as thoughtful and as engaged as ever. Simon Allford, president of the RIBA, travelled to Ahmedabad last year to award Doshi his Gold Medal, causing Doshi to recall the time in 1953 when Le Corbusier received news that he had the same award and “said to me metaphorically, ‘I wonder how big and heavy this medal will be.’” At the time of his death, a new documentary, The Promise – Architect BV Doshi (2023), was in final preparation and an exhibition, Architecture is Within Us: The Selected Works of Balkrishna Doshi, had just opened at the Boston Architectural College Library (BAC).

Doshi once recalled that his grandfather had taught him reverence: and later described “living with grace”, as one of his highest aims. That quest, and a sense of wonder at life, is apparent in the slight, graceful figure of Doshi captured on video, animatedly speaking, teaching, or answering questions. Roshini Vadehra was struck by his “childlike enthusiasm and warmth for everything and everyone that he came in contact with”.

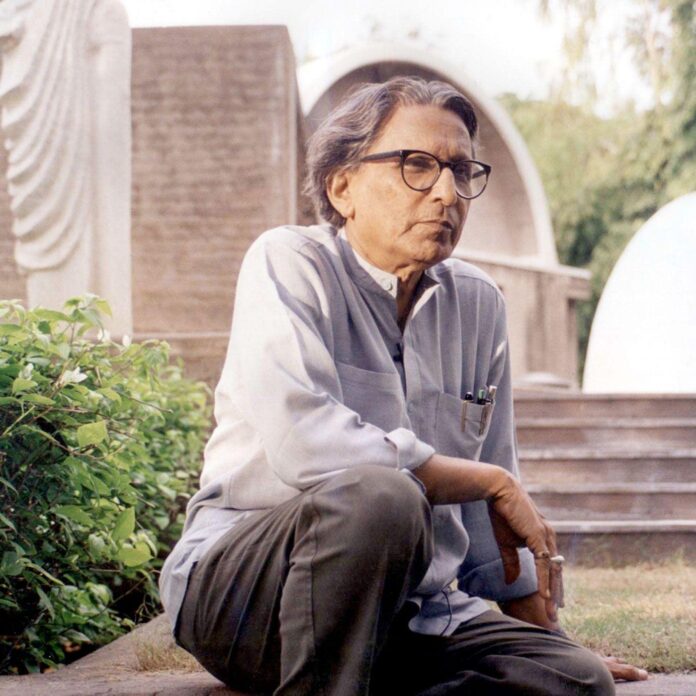

Balkrishna Doshi: architect and fine artist Vadehra Gallery

As an architect, Doshi was less an auteur and more an empowering figure who took inhabitants and visitors on a voyage of discovery, through architecture and the environment. “I became aware of the close give-and-take relationship between the land, resources, climatic conditions and people very early in my life,” he writes in Paths Uncharted. “I also realised that our world consisted of distinct regions, each with its own characteristics that included distinct architectural practice unique to each region.”

A new kind of modernity

In the patent integrity of his approach—to affordability, livability, a concern for climate and materials, and the value of shared social space—Doshi had much in common with Hassan Fathy (1900-89), the visionary Egyptian architect of a preceding generation. Both were at home in the avant-garde of their day, but both were far ahead of their respective times in creating a new kind of modernity, one that promoted local culture and sustainable construction techniques, that enabled passive cooling in hot climates, and an “architecture for the poor” with a genuine focus on how their buildings would be lived in.

In Paths Uncharted Doshi recalled how his life had been balanced between the urban and the rural to match the balance in which he held the forces of innovation and tradition. He described his memories of village life and agricultural economy; balanced with those of 1950s Paris, working with Le Corbusier and to the “different impressions of the artistic attitudes to urban life and the world of tomorrow.”

“Between these two realms—searching for the constants between these two worlds, rural and metropolitan,” he writes, “lies my architectural career. In my life and my work, the effort has been to combine the virtues of both and to find a balance between these two worlds.”

Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi; born Pune 26 August 1927; Pritzker Prize 2018; Padma Bhushan 2020, Padma Vibhushan 2023 (posthumous); RIBA Royal Gold Medal 2022; author of Paths Uncharted (2019); married 1955 Kamala Parikh (three daughters); died Ahmedabad 24 January 2023.