The saga of the book “that doesn’t exist” began on 27 February 2020, when I was contacted by an academic with some surprising news. She had heard that the Louvre had produced a small book devoted to a new and detailed scientific examination of Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi. My reaction was one of astonishment.

We had been told that no one from the Louvre had been granted access to the painting since its notorious sale at Christie’s in New York in November 2017, where it had fetched a record $450.3m. In the intervening period, the picture had neither been available for public exhibition, nor scholarly scrutiny. It had disappeared.

At the same time, the provenance of the picture had unravelled, and the painting had been variously re-attributed by experts to artists in Leonardo’s workshop, such as Boltraffio, Luini or even later handsThe book Léonard de Vinci. Le Salvator Mundi (Louvre editions/Hazan, 2019) was co-authored by the Louvre curator Vincent Delieuvin, together with Myriam Eveno and Élisabeth Ravaud of the Louvre’s scientific laboratory C2RMF. It had been published to coincide with the Louvre’s blockbuster Leonardo da Vinci show (24 October 2019-24 February 2020), in which the Salvator Mundi was intended to have a starring role—though in the event the picture had proved to be a dramatic no show. Was The Art Newspaper planning to review the book, I was asked by the academic? Had we seen a copy?

This news of a book was more than intriguing. The Louvre’s opinion on the attribution of the painting to Leonardo da Vinci was the critical piece of information that the art world had been waiting for; after all no other museum had so many Leonardos in their collection (notably the Mona Lisa, St John the Baptist and Virgin and Child with St Anne) and therefore access to so much accumulated expertise and comparative technical analyses. So, when the picture failed to materialise in the exhibition, the scholarly dismay was palpable

Now it appeared that the Louvre’s experts had not only gained access to the Salvator Mundi —supposedly last sighted on the super yacht of its owner Saudi Prince Mohammed Bin Salman—but had also secretly examined it in their Paris laboratory. And they had produced a 46-page book to boot! So, what was the Louvre’s definitive verdict on the authenticity of the picture and how would that affect the picture’s value?

The academic explained to me that she had searched in vain for further evidence of the elusive publication, or even any mention of it online. However, Dianne Modestini, the expert who had devoted so many years to painstakingly restoring the Salvator Mundi, had, “by a fluke”—as Modestini subsequently told me—come across the book in the flesh. And not only that, but she had had a chance to scan it and study it in detail. Apparently, the book had been available, briefly, to purchase in the Louvre bookshop in December 2019, during the exhibition’s run, buried amid a pile of exhibition catalogues. This “secret book” had been innocently acquired for the princely sum of €8.

Of course, I immediately searched online for any trace of the book but turned up nothing. So, my next point of call was the Louvre press office. Could they tell me about the book and where I might get hold of it? “No such publication exists,” I was told emphatically. However, the spokesperson confirmed that “the book was a project in case the Louvre got the chance to present the painting. As this has not been the case, it is not going to be published”.

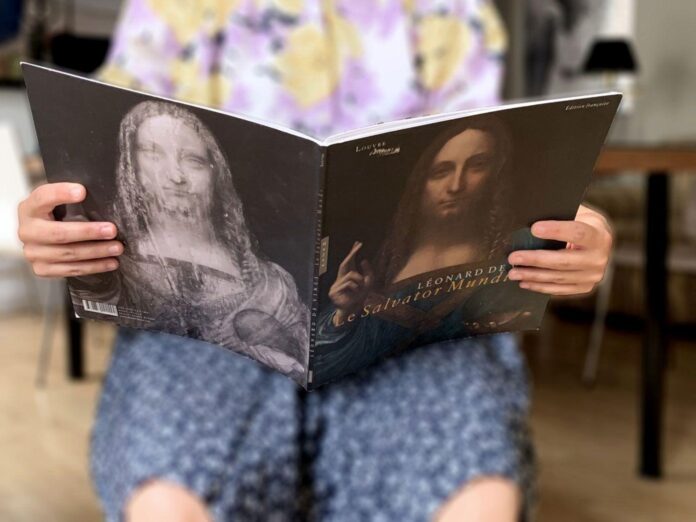

But the printed book certainly existed—as the picture accompanying this article shows—and we soon had access to its contents. Our exclusive report “How the Louvre concealed its secret Salvator Mundi book” was published online on 31 March 2019 and on the front page of the April print edition of The Art Newspaper. Here we revealed the publication’s existence and its conclusions. We also discovered why its emergence was proving such an embarrassment to the Louvre, whose stated policy is “not to comment on a work in a private collection if the work isn’t on display in one of its exhibitions”. And, most significantly, our article also quoted an excerpt that showed that the curator of the Louvre’s Leonardo retrospective, Vincent Delieuvin, had come down in favour of the painting as autograph.

Emmanuel Macron, president of France, receives the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman at the Elysee Palace in Paris, 10 April 2018. The Louvre book on the Salvator Mundi, withdrawn form sale in 2019, confirmed that Saudi Arabian Ministry of Culture was indeed the owner of the picture Ammar Abd Rabbo/Abacapress.com

The book, also, for the first time, unequivocally stated that the owner of the painting was the Ministry of Culture, Saudi Arabia. This confirmed the New York Times 2017 scoop that the successful bidder at auction had been a close ally of, or proxy for, Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince. Delieuvin had also told me, in advance of the Louvre exhibition, that the Louvre were producing two alternative versions of the exhibition catalogue: one in the event that the Salvator Mundi was loaned to the exhibition, the other if the loan failed. This was borne out by a leaked proof of the former, sporting the Saudi Salvator on the cover, accompanied by its Saudi picture credit. (In the printed version of the catalogue, Cat no.157 is missing, and the Belle Ferronière adorns the cover instead.)

Does the secret book contain the material that would have been in the catalogue, if the loan had arrived in time for the exhibition opening? This would explain why the material in the book is quite generalised and fails to stand up to peer scrutiny of the conclusions of the technical study. It feels and looks like a slim catalogue supplement.

We therefore speculated that the book may have been prepared to help facilitate the eventual loan of the painting by the Saudi Culture Ministry—some time after the exhibition opening. In a separate piece of investigative journalism, we reported that the French government had made an amendment to an indemnity decree to allow the picture to turn up, fashionably late, up to and including 31 December 2019—over two months into the exhibition’s run. The book was printed in Turin that December, so the Louvre must have been supremely confident at this point that the picture was en route.

So, what happened in December 2019 to precipitate the sudden withdrawal of the loan, and a simultaneous instruction to destroy the copies of the book? Had the Louvre’s interests clashed with the political interests of France and its major partner Saudi Arabia, in the wake of the murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi? Two acclaimed documentary films have since come out—The Saviour for Sale (April 2021) and The Lost Leonardo (June 2021)—yet we are still none the wiser. Perhaps, as the world’s media turned its attention to the Khashoggi murder trial and verdict in December 2019 (with the West universally denouncing it as a whitewash), the politics were too delicate for Saudi Arabia’s cultural rehabilitation.

The book resurfaces

From her perusal of the book, Modestini told us that the Louvre’s laboratory had examined the painting back in 2018, subjecting it to non-invasive procedures, namely XRF mapping as well as new IR scans, X-radiography and photomicrography. She made a plea in our pages for the Louvre to share their high-resolution digital files, as she believed her own knowledge would be a useful component in the all-important interpretation of the scans. But the Louvre’s official line continued to be that the book didn’t exist. And the scans may not have been theirs to share….

We returned to the book again in January 2021 with an article focusing on its finding of the late addition of Christ’s “blessing hand” in the picture’s evolution, and a new US digital analysis of the painting that claimed to provide further insights into its authorship. But it was not until a few days before the screening of the French director Antoine Vitkine’s The Saviour for Sale—premiered on France’s Channel 5 on 13 April—that the Louvre’s secret book dramatically resurfaced again.

In the film, two anonymous officials in President Emmanuel Macron’s government make the explosive claim that the state run Musée du Louvre had not only questioned the attribution of the painting to Leonardo, but also that, on this basis, Macron had taken the decision that the Louvre should not exhibit the painting as autograph (along with refusing an alleged request to exhibit it alongside the Mona Lisa). As a result, the loan offer from Saudi Arabia was withdrawn. The Louvre’s negative verdict on the painting’s authenticity, the officials said, followed a “top-secret” examination of the picture undertaken by C2RMF in June 2018. (This date coincided with the French government issuing a decree of immunity from seizure for the picture lasting up to 3 March 2020.)

But how did that square with the Louvre’s positive verdict on the Leonardo attribution, as summarised in the suppressed book? Surprisingly Vitkine’s film made no mention of the book, which, as The Art Newspaper had reported, also presented conclusions based on a secret C2RMF 2018 analysis.

The Louvre would not comment on the film’s politically damaging revelations, but the contents of the book “that didn’t exist” were suddenly leaked to a few select media outlets (notably the New York Times) in PDF form, in effect providing the Louvre’s response: that is comprehensively contradicting the anonymous claims made by the French government officials in Vitkine’s film. With the pdfs of the book now freely circulating on email to any journalist who wanted them, we decided it was time to provide a detailed analysis of the book, and, for the avoidance of doubt, to list its key findings.

We reported that in his preface to the book, the Louvre’s then President, Jean-Luc Martinez, states unambiguously that “The results of the historical and scientific study presented in this publication allow us to confirm the attribution of the work to Leonardo da Vinci, an appealing hypothesis which was initially presented in 2010 and which has sometimes been disputed. Showing the painting alongside other works by the master from the Louvre is therefore a major event for studies of Leonardo and in the history of the museum.” Alas, as we know, this event—which the preface assumes is taking place—never happened.

Given this positive verdict, we also asked Vitkine why he hadn’t mentioned the book in his film. He explained to us that following our March 2020 revelations, he had contacted Martinez who “explained that the Louvre does not talk about pictures that it does not own, and it doesn’t have the right to research pictures that don’t belong to national collections.” “The Louvre’s official line,” continued Vitkine, ” is that the book ‘doesn’t exist’.”

“My film’s focus, however,” he explained, “was an investigation into a political decision made by Macron in September 2019 [just before the Louvre exhibition opened], so I concentrated on that. I am very respectful of the Louvre’s scholarship, and I can’t explain the contradictions between the dossier that went to Macron concerning the Louvre’s findings [June 2018] and the secret book, which was paid for by Saudi Arabia. I am confident, however, that Macron did not have access to [the book] when he made his decision.” The book indeed, was only printed in December 2019, just prior to its momentary appearance amid the Christmas bustle of the Louvre bookshop.

It is now almost certain that the Louvre book will never be officially published. Its moment has passed, though its findings have now been widely shared. But as a postscript to the saga, The Art Newspaper correspondent Martin Bailey reported in an article, that the Madrid museum—in a catalogue focused on its own early copy of the Mona Lisa—had relegated the Salvator Mundi to the category of “attributed works, workshop or authorised and supervised by Leonardo”, rather than works by the hand of the master.

Vincent Delieuvin, who co-authored the suppressed Louvre book, had also contributed an essay to this catalogue. As Bailey observes, Delieuvin is not particularly forthcoming about his own opinions of the Saudi Salvator Mundi, though he notes that Delieuvin’s essay refers to “details of surprisingly poor quality” and interestingly Delieiuvin concludes: “It is to be hoped that a future permanent display of the work will allow it to be reanalysed with greater objectivity.”

• Read all of our coverage on the Salvator Mundi here and read our special coverage on the five-year anniversary of the sale here