The idea for a hit, two-venue summer group art show about the unlikely subject matter of boxing, with an all-star lineup of established and up-and-coming artists, was sparked by an idea that star artist Eric Fischl had a while ago. He thought about the boxer as a “metaphor” for the artist in the process of creativity, said chief curator Sara Carson, who co-curated the exhibition with Fischl.

Little did he and his eventual fellow curators know what a rich vein they were about to mine. “I have to say, as a curator, I’ve never been involved in a show that revealed itself to be so deep within this topic,” said Carson in a phone interview with Artnet News.

Installation view of “Strike Fast, Dance Lightly: Artists on Boxing,” at FLAG Art Foundation. Left: Rosalyn Drexler, In The Ring (2012). Center: Amoako Boafa, King (2021). Right: Rosalyn Drexler, Prize Fight (1997) Photo by Stven Probert.

The end result is “Strike Fast, Dance Lightly: Artists on Boxing,” which features 100 artworks spread across both The Church in Sag Harbour on Eastern Long Island (through September 3) and at the Flag Art Foundation, the nonprofit space in Chelsea founded by collector Glenn Fuhrman (through August 11). Fischl and his wife and fellow artist April Gornik acquired the historic former Methodist church in Sag Harbor several years ago and turned it into a center for artists and the community. They offer artist residencies, as well as public space for programs and exhibitions.

Installation view of “Strike Fast, Dance Lightly: Artists on Boxing” at the Flag Art Foundation. Photo by Steven Probert.

To give even a sampling of the star-power lineup: artists featured at the The Church include Derrick Adams, Diane Arbus, Zoe Buckman, Jim Campbell, Carroll Dunham, Fab 5 Freddy, Fischl himself, Barry Flanagan, Jeffrey Gibson, Lyle Ashton Harris, Howardena Pindell, and many more.

The Flag Art Foundation presentation includes John Ahearn, George Bellows, Amoako Boafo, Andrea Bowers, Katherine Bradford, Rosalyn Drexler, Chase Hall, Reggie Burrows Hodges, Ed Ruscha, and Carrie Mae Weems.

Carson highlighted that among the focal points of The Church show is the parallel that runs between the boxer and the artistic struggle—and the question of what is worth fighting for. It may come as a surprise to some viewers, she noted, as to how many women artists are featured in the show because they have tackled the matter of boxing in their work.

“We discovered women artists using boxing as a shorthand for victimization or an idea of empowerment. The fact that the boxer was like a Schroedinger’s Cat… both a winner and a loser,” is a through line of the show, said Carson.

The Flag Foundation immediately got on board after hearing about the idea, though its director Jonathan Rider put his own twist on the presentation in terms of a historical framework. This includes a selection of Roman artifacts, iconic 19th- and 20th-century images by Eadweard Muybridge, George Bellows, and some of the first moving images created by the Thomas Edison Company, he said.

“These are presented in dialogue with artworks by 30 contemporary artists, including newly commissioned pieces. Artists Caleb Hahne and Cheryl Pope, who were both amateur boxers, address the physicality inherent to the sport from their own experiences; other artists respond in metaphorical and poetic ways, such as Vincent Valdez’s suite of oil paintings that look at Muhammad Ali’s legacy by those who eulogized him at his funeral. What was most surprising in organizing the show was the various ways artists continue to reimagine and reinterpret the boxer and boxing, from a cultural symbol of agility, endurance, and physical strength, to the mythos, spectacle, and violence of the sport.”

Fischl took it even deeper when explaining his own inspiration and methodology. The artist said that it was actually the fact that he had reached a point in his creative life “where the nagging doubts were stronger rather than farther away. Do I have anything left? Can I go back out there again? What do I have to offer in terms of inspiring myself?”

This led him to meditate on two works specifically. The first was , one of the few remaining bronze sculptures from 3000 B.C.E., which he described as “a remarkable sculpture of a man of a certain age who has been a boxer all his life. He’s sitting down. His hands are wrapped and he’s sitting there looking over his shoulder. Is he hearing his name called out or is he having an internal conversation about whether he wants to go back out there or not?”

The second work was a Pierre Bonnard self-portrait in which the artist portrays himself as a boxer, though it’s a painting in which he’s “clearly not a professional boxer,” as Fischl pointed out. “He’s posing as though he was willing to put up his dukes. He’s sort of feigning strength to himself looking in the mirror, this tough-guy stuff. It resonated with me, that pureness of perfection and beauty, the clarity of expression” that an artist is trying to communicate and deliver all of his life, but which can also be an “extraordinary burden. That’s what gave me the idea for the show.”

Here are a selection of highlights from the summer group shows.

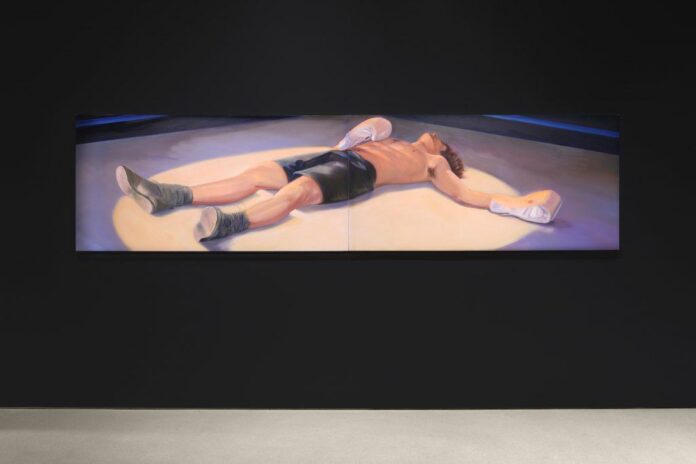

Installation view of “Strike Fast, Dance Lightly: Artists on Boxing” at the Flag Art Foundation.

Photo by Steven Probert.

Carrie Mae Weems, The Boxer (2012). Image courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery.

Amy Bravo, Congratulations Hero! (2023). Image courtesy the artist.

Installation view of “Strike Fast, Dance Lightly: Artists on Boxing” at FLAG Art Foundation. Photo by Steven Propert.

Installation view of “Strike Fast, Dance Lightly: Artists on Boxing,” at The Church in Sag Harbor.

Photo by Gary Mamay

Installation view of “Strike Fast, Dance Lightly: Artists on Boxing,” at The Church in Sag Harbor.

Photo by Gary Mamay