Some works of art are so magnetic their prices are destined to soar higher and higher with every passing era. Others seem to be trailed by bad karma from auction to auction. And then there are those that remain forever shrouded in mystery.

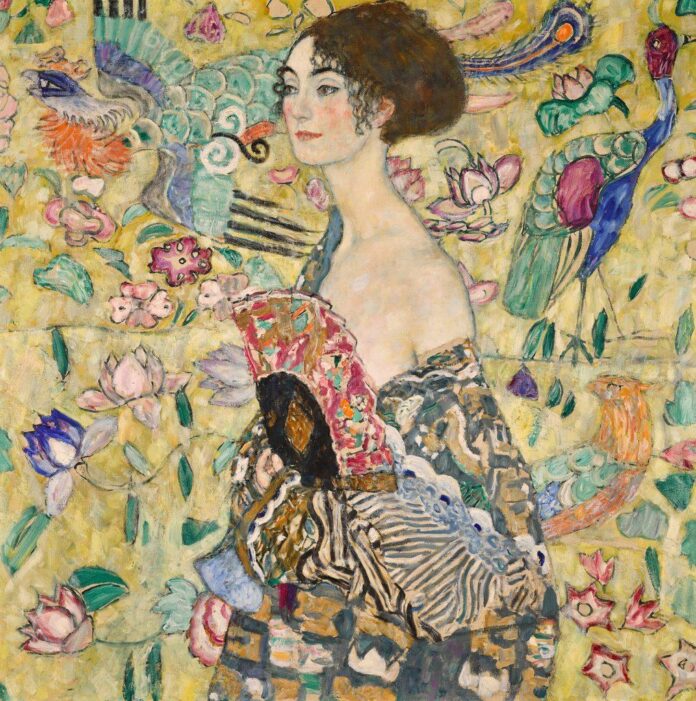

Such is the fate of Gustav Klimt’s , a portrait of a discreetly smiling Viennese beauty, at once sacred and profane, that fetched $108.4 million at Sotheby’s last month. Klimt’s final finished painting, it set a new auction record for the Austrian —just like it did the last time it came up for sale in 1994. And, just like the last time, no one knows where it went.

Leave it to an auction house to do something clandestine in plain sight.

“Sometimes works just disappear,” said David Nash, whose 35-year tenure at Sotheby’s saw him rise from porter to head of the Impressionist and Modern art department before stepping down in 1996. “I never found out who bought the Klimt. I never found out who bought Picasso’s .”

This lack of clarity irked Nash because he was responsible for bringing Sotheby’s the estate of Wendell Cherry, the Louisville-based founder of hospital giant Humana, which included the Klimt. The winning bid was placed through a representative of Sotheby’s client services. After that, Nash found, the track went cold.

Now, almost 30 years later, was back on the market, coming seemingly out of nowhere. Its provenance states that the family of the current owner acquired the canvas in 1994. Perhaps a generational changing of the guard resulted in its first public exhibition in Vienna in 100 years, at the Belvedere Museum in 2021.

Will vanish again for decades? Your guess is as good as mine. The auction house is mum.

But there’s a backstory worth telling—if only because the Klimt is the brightest spot at a rather uncertain moment for the art market. On the one hand, we are seeing a clear contraction. Christie’s just reported a 23 percent drop in its sales during the first six months of 2023 from a year ago, and its main rivals are on a similar trajectory.

Helena Newman, auctioneering Gustav Klimt’s record-breaking Dame mit Fächer (Lady with a Fan) by Gustav Klimt. Photo by Haydon Perrior, Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

On the other hand, there remains a bracing desire at the top of the market to compete for rare and exquisite artworks, as evidenced by the Klimt.

“It’s very targeted,” said Philip Hoffman, the CEO of the Fine Art Group, whose clients were bidders and buyers in New York in May. “There’s no lack of interest from top clients. The middle clients are thinking about their use of money. The challenge is interest rates.”

The Klimt painting, with its unmistakbly East-Asian motif, is also the clearest indication since the pandemic that Asian buyers are back at the top of the market. Four bidders went after the work, which was on an easel in Klimt’s studio at the time of his death. Three of them represented Asian clients. The winner was Patti Wong, a former Sotheby’s rainmaker, who later said she bought the painting on behalf of an anonymous Hong Kong client. (It was a third major Klimt painting at auction since November heading to Asia.)

Within minutes, the guessing game began. Let’s walk through what we know.

While at Sotheby’s, Wong was known to work closely with many high-profile, mega-rich Asian clients, including the Taiwanese financier Pierre Chen and the Hong Kong-based collector Joseph Lau. Sitting in the salesroom on Bond Street in London, Wong displayed absolutely no hesitation in bidding. It seemed she would go to the moon for the Klimt if she had to.

Gustav Klimt holding one of his cats in his arms, in front of his studio in Vienna, 8th district, Josefstaedter Strasse (ca. 1912). Photo: Moriz Naehr. Courtesy of Imagno/Getty Images.

Perhaps it was a strategic move. Wong recently left Sotheby’s after three decades to launch Patti Wong & Associates, soon joining forces with Hoffman’s Fine Art Group. She had a reason to flex—and she did. After the sale, Wong said she bought the painting for a Hong Kong client.

This could mean anything, of course: from someone with a business to someone with a on the island.

Some people used this loophole to begin pointing at Chen, a Taiwanese billionaire, whose collection is now on view at Tate Modern in London. Among the works lent to the show “Capturing the Moment” by Chen’s Yageo Foundation is David Hockney’s 1972 , which fetched $90.3 million at Christie’s in 2018. It was the record price for a work by a living artist at auction at the time. Another painting, “Le Marin” by Pablo Picasso, was famously punctured by a rod ahead of its auction at Christie’s in 2018, when it was estimated at $70 million. But Chen is based in Taiwan, not Hong Kong, so he was probably not the buyer of the Klimt.

Meanwhile Lau, who is a fugitive in Hong Kong, is no stranger to paying big prices for Western masterpieces, but he’s yet to cross $100 million. In 2006, he bought Warhol’s Mao portrait for $17.4 million, the price that seems a steal now. In 2015, he paid $41.7 million for Roy Lichtenstein’s and $67.4 million for Pablo Picasso’s . But recently, Lau has been recently a seller, parting with his wine, Chinese works of art, and a trove of Hermes bags to make up for his losses in the stock market.

Soon, another name surfaced as a potential buyer: Rosaline Wong, who has emerged as one of the top players in the region. It’s easy to see why she might be a candidate. While somewhat of a behind-the-scenes figure, Wong, who is in her early 50s, has been an “aggressive” buyer over the past decade. And she’s connected to the highest-wattage buyers, having been romantically linked to Lau and, in recent years, to billionaire Henry Cheng.

Gustav Klimt, Adele Bloch-Bauer II (1912). ©2014 MoMA. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar.

What’s known is that Wong’s interests range from Chinese works of art to trophy 20th-century paintings—and that she is among a small group of people in the world who can easily spend $100 million on a work of art, according to people who’ve dealt with her. Once, an auction of Asian art tanked when Wong wasn’t able to participate due to a death in the Cheng family.

“She’s a force,” said a top executive at a major auction house, a sentiment echoed by others. But a force for whom? The people I spoke with couldn’t definitively say whether she buys for herself or is a public front for investors who prefer to keep their art transactions outside of the public eye.

“No one can answer that question,” the executive said. “She buys. She pays.”

Wong may be useful to those who want to be discrete about their lavish lifestyles, another auction executive said. “They need people like Rosaline Wong to help facilitate moving stuff around without being flagged,” the person said. “Some billionaires don’t like being seen buying things at a major auction house. Then they can structure the transfer of ownership however they want, sometimes in creative ways.”

Since the pandemic, however, Wong has embraced a more public profile, and it hasn’t gone unnoticed. She collaborated with Christie’s on exhibitions of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Francoise Gilot and Adrian Ghenie/Francis Bacon doubleheader. Each show coincided with a significant auction by the featured artists.

Most recently Rosaline Wong has surfaced as a partner in an art investment fund set up by Zheng He Capital. The marketing materials for the fund, ZH Bella Romaine Fund L.P., describe Wong as one of the world’s top art collectors and someone who’s been involved in $4 billion worth of art transactions. The fund lists Larry Gagosian as an advisor.

While the whispers about are just that, it would not be the first time Wong has been linked to a major Klimt. In November, the reported that Wong’s company HomeArt was listed as the lender of not one but two Klimt works to “Golden Boy–Gustav Klimt,” an exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

Gustav Klimt’s Serpents aquatiques II (Les Amies), (1904-1907). Private collection. Photo © Akg-Images/Erich Lessing.

One of them, (1912), fetched $87.9 million at Christie’s in 2006 as part of the group of paintings restituted to the Bloch-Bauer heirs. The work was acquired then by Oprah Winfrey, who sold it 10 years later for $150 million in a deal brokered by Gagosian.

The second Klimt is 1904-1907), which used to belong to Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev. He sold it to an anonymous Asian buyer for $170 million in 2015. Earlier this year, the painting was included in an exhibition at the Belvedere Museum.

I broke the news about the two deals in 2017, but I wasn’t able to confirm the name of the buyers at the time, and I didn’t realize that both paintings were acquired by the same person or entity. Curiously, both were purchased during a contraction in the art market, just like today.

Could Rosaline Wong’s be behind the latest Klimt sale at Sotheby’s? Advisor Patti Wong declined to comment.

Sources tell me it so happens that Rosaline Wong is launching a fractional ownership fund specializing in museum-quality works for a broader pool of investors. Klimt’s Viennese beauty, her fan coyly outstretched, may just be the kind of girl to seduce them.