What if you got to see every object you own—every last item of clothing, tech gadget, home good, personal knick-knack, and food scrap in your fridge—arrayed in total before you? Would it be a collection reflecting your unique taste and personality, or would it simply mark you as another avid consumer? Just what would your stuff say about you?

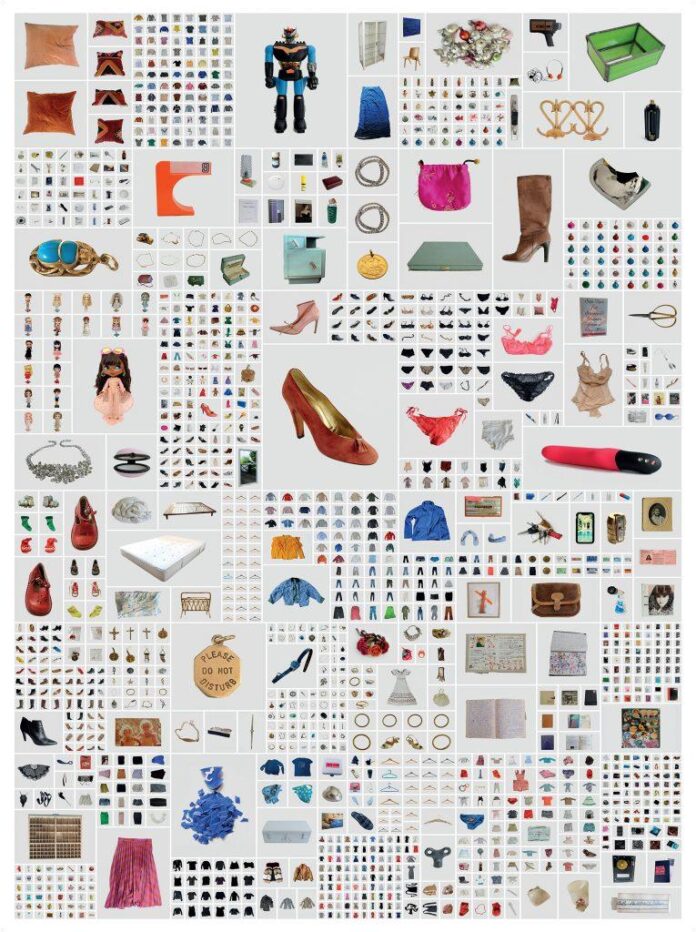

This, Barbara Iweins found out when she embarked on an admittedly “obsessive” mission to photograph all of her possessions. Over about four years, she systematically snapped images of 12,795 items in her home—an archive that slowly transformed what began as a project of introspection into a memorial to the objects she’s bought, collected, and cherished.

“I have nothing that is particular,” Iweins told Artnet News about her belongings. “I’m a very regular person with very regular possessions—but that represents life and that’s also the beauty of it.”

A mug. Photo: Barbara Iweins, courtesy of the artist and Delpire & Co.

In fact, Iweins’ photographs, now collected in a hardcover, Katalog, offer no shortage of relatable content. The book, which was shortlisted for the 2023 Rencontres d’Arles Author Book Awards, is organized according to the rooms in her Brussels home and contains items that will not be unfamiliar to readers.

Her kitchen is represented by an assortment of mismatched cutlery and brightly colored cleaning products, and her hallway an assemblage of random gold ornaments. There’s a collection of Fire King glassware in her living room, pills in her medicine cabinet, screws in her toolbox, and army figurines in her son Pieter’s room.

“It’s a whole object about objects,” Iweins said of the book, “but in a way, it’s about stories.”

A family portrait. Photo: Barbara Iweins, courtesy of the artist and Delpire & Co.

Iweins began her photographic practice in 2009, focusing largely on portraiture. The decision to turn her camera onto herself emerged in 2015, during a period of uncertainty, she said, following a divorce and a move from Amsterdam, where she had lived for a decade, back to her native Brussels.

“When I arrived in Brussels, I was still in this very unstable period of my life,” she remembered. “I really felt this urge to know what it meant to be a single woman with three children. I wanted to see that flat on the ground.”

But since laying out all her worldly goods on the ground would be spatially and practically impossible, Iweins turned to photography. She developed a system, shooting objects room by room, cataloguing them in a spreadsheet, then analyzing them as you would a dataset.

These latter observations are scattered throughout Katalog. “37 percent of the Playmobil [toy figures] in the house are bald,” reads one, and another, “the dominant color of [my] house is blue.”

A tab of Xanax. Photo: Barbara Iweins, courtesy of the artist and Delpire & Co.

These stark assessments match the candor Iweins displays in her images, which unflinchingly delve into the most intimate corners of her life—from her medicine cabinet to her collection of sex toys.

“I really wanted to show not an idealized life, but its back side, like my underwear with holes in them, because that’s part of life. I wanted to show it all,” she explained.

Just as telling, she added, was what the project revealed about her relationship with clothes: “The fact that I had to photograph them was painful. You realize you have things that you don’t see anymore.”

A trenchcoat. Photo: Barbara Iweins, courtesy of the artist and Delpire & Co.

The specter of mass consumption haunts Katalog, but the project has been just as personal for Iweins. She described the process of photographing her possessions as “therapeutic,” her earthly footprint (quite literally: Iweins owns about 100 pairs of shoes) serving as “proof that these objects and this life existed.”

But more to the point, what does her stuff say about her?

“That I’m a neurotic person?” she joked. “For me, the world is chaotic and life is absurd. I see the objects I like as protection, my stable reference. I know it’s a bit sad to say, but they’re always going to be there. People can disappear, people can die—but objects are always there.”

Katalog is published by Delpire & Co.

More Trending Stories: