Documentaries about groundbreaking artists often adhere to a paradoxically predictable template. Writing recently in Filmmaker about the new documentary Nam June Paik: Moon Is the Oldest TV, Vadim Rizov expressed dissatisfaction with the “talking-heads-plus-archival assemblage” as a genre; attempts at “educating the curious but uninformed while offering rare archival footage and/or fresh insights for the already initiated” invariably err on the side of the former, making for ploddingly expository viewing. A critic invested in the formal possibilities of cinematic nonfiction (or an art lover hungry for fresh insights) is entitled to feel enervated watching something seemingly designed to be played back at 1.5x speed like a podcast—but, as Rizov also admits, such films fulfill a pedagogical purpose, offering glimpses of the work, critical soundbites, and capsule narratives of its context, making it approachable for a nonspecialist audience.

As an attempt to champion the work of an artist on the outskirts of the canon, This World Is Not My Own, a portrait of Nellie Mae Rowe, is an inadvertent advertisement for the competently executed paint-by-numbers documentary. The film is larded with stylistic eccentricities that have little to do with Rowe’s work, it struggles to impose a critical perspective on her art or life and does not question the wider implications of the story it tells about a “folk artist”.

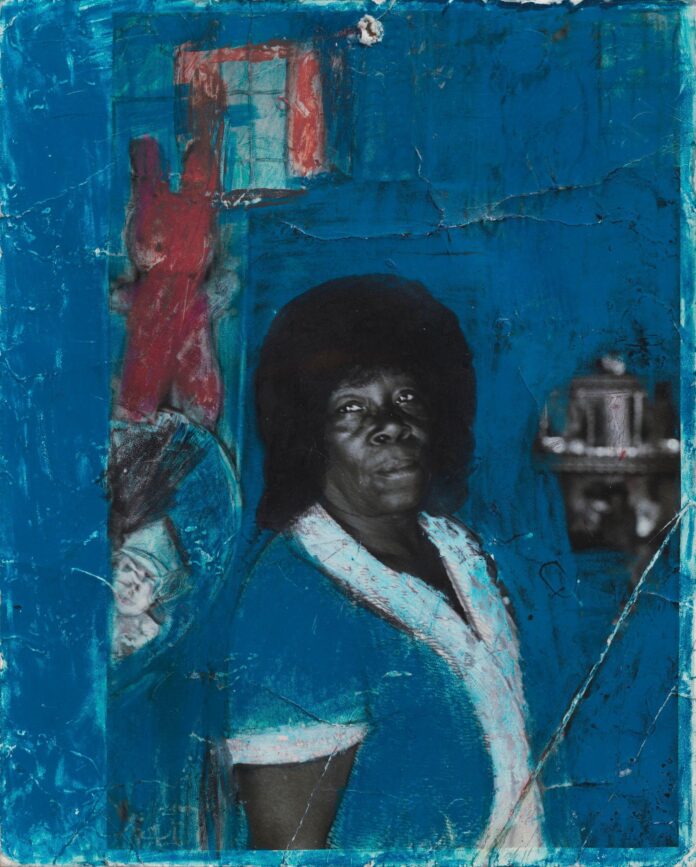

Animated Nellie Mae Rowe by her home known as the “Playhouse” © Opendox, Photography by Petter Ringbom. Character Animation & VFX by Kaktus Film

Born in Fayetteville, Georgia, on 4 July 1900—her father was formerly enslaved; her mother was born the year of Emancipation—Rowe lived a hardscrabble life defined by farming and domestic labour before returning, in late middle age, to the art practice she had explored during the rare free time afforded to her in youth. Scenes in the documentary of an elementary school art workshop, juxtaposed with Rowe’s own description, in a 1970s interview, of her art as “play”, posit her work as the reclamation of a childhood effectively stolen by institutional racism and poverty.

Rowe’s worked most expressively with materials that were manufactured specifically to facilitate play, including crayons, colored pencils and markers. She also made sculptures from chewing gum—only her own chewing gum, an interviewee clarifies in the film. Arranging people, animals and autobiographically, symbolically or spiritually significant objects across a flat perspective, many of her works, like Chagall’s, appear like still lifes unbound by the strictures of stillness or life, gravity or realism.

Not that Rowe knew a thing about Chagall—as one of her great-great-nieces says in an interview. While much of the contemporary art world rethinks the hierarchies that are reinforced when a self-taught genius such as Rowe is defined as an “outsider” artist—outside of what?—This World Is Not My Own’s interviewees largely accept that framing. This is potentially intriguing, but the discussion is naggingly incomplete. The editing structure parallels Rowe’s life with that of Judith Alexander, her gallerist and establishment champion in Rowe’s later years; this underlines the many comments about their race-transcending friendship while remaining basically incurious about their professional partnership and Rowe’s reception.

Animated Judith Alexander and Nellie Mae Rowe © Opendox, Photography by Petter Ringbom. Character Animation & VFX by Kaktus Film

There is as well a basic lack of insight into the art itself. Rowe’s large extended family, who knew her as a somewhat eccentric older relative who enjoyed expressing her creativity and encouraged them to do the same, offer precious reminiscences. But their child’s-eye-view is not deepened by other talking heads, whose comments are generic to the point of downright unconvincing, as in the scholar who places Rowe in the very general lineage of Afrofuturism (enabling the filmmakers to insert a clip from Black Panther).

The directors—this is a “film by Opendox”, co-directed by Petter Ringbom and Marquise Stillwell, also partners in the urban design consultancy Openbox—in general allow their attention to be yanked this way and that by their talking heads. Struggling to impose a through-line beyond general chronology, they mostly embellish digressions that reduce the history of Black life in the South to a string of unconnected anecdotes.

Rowe, who died in 1982, lived to see herself become an admired and analysed artist, the subject of multiple museum exhibitions. A more recent show, currently touring the US, includes a miniature replica of her home, which she called the “Playhouse”. An intricate and evolving junk-sculpture habitat, sadly now demolished, the Playhouse was a local attraction and evidence of Rowe’s resourcefulness and responsiveness to her environment.

A similar replica is used in the film for its most extensive gambit: it is the setting for imagined scenes from Rowe’s life, with Uzo Aduba playing the artist in motion-capture animation and delivering “dialogue based on direct quotes”. These sequences are inexplicably washed-out monochrome in the film’s first half, before switching to colour, and less evocative of Rowe’s work than the floating animations featuring segments of her drawings that cohere into the whole—a more straightforward technique but one which, when layered over the relevant “talking-heads-plus-archival assemblage”, captures some of their essential mischief and mystery. As a film whose mandate is implicitly educational, This World Is Not My Own will likely play better in the classroom than on public television; Rowe’s story is inspiring and her art joyful, but the movie makes her seem mostly merely cute.

- This World Is Not My Own screens at South by Southwest in Austin, Texas, on 18 March and at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC, on 21 March.

![The Art Angle Podcast: Why Art Biennial Superstars Exist in a Parallel Universe [Re-Air]](https://usaartnews.com/wp-content/uploads/VRHol2mxCigZMbXM4viOzcXxbmh63PSdyZ2EUse4-80x60.jpg)