A new publication chronicles the Spanish artist’s early life in Paris, including police harassment and stigmatization as an anarchist.

The Picasso case is growing every year, writes Coen-Solal. It’s filled with reports, interrogation transcripts, residency permits, ID photos, fingerprints, rent receipts, and naturalization applications. Pablo Picasso moved to Paris at the turn of the century, where, according to the author, he was soon branded as a threat to the state.

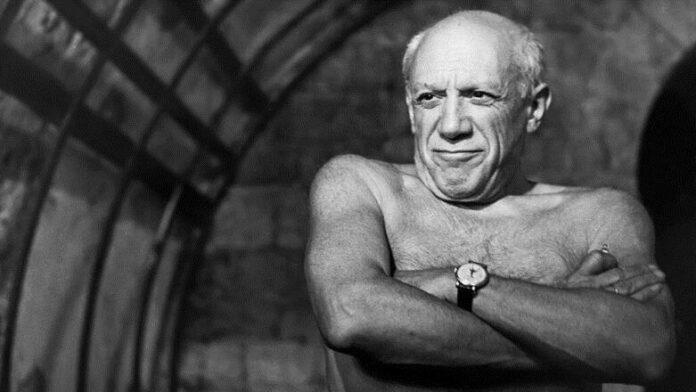

The discovery of Picasso’s police files was a real shock, says Coen-Solal. She says she couldn’t believe how many times Picasso had to go to the police station to get the identity papers needed for a foreigner, which had to be renewed every two years, with his fingerprints and identification photos that made him look like a criminal. In the case of Picasso, opened in 1901, when he was not even 20 years old, the police wrote that he was a threat to the country.

She describes her research as a scientific treasure hunt, for which she collated data as she traveled between police and the National Archives, and holdings at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

“This is how I was able to compare, for example, two police files at the same time: the Picasso case and the case of Sante Geronimo Caserio, the young Italian anarchist baker who assassinated the President of France in 1894,” she says. “Picasso was described by the police as much more dangerous than Caserio!”

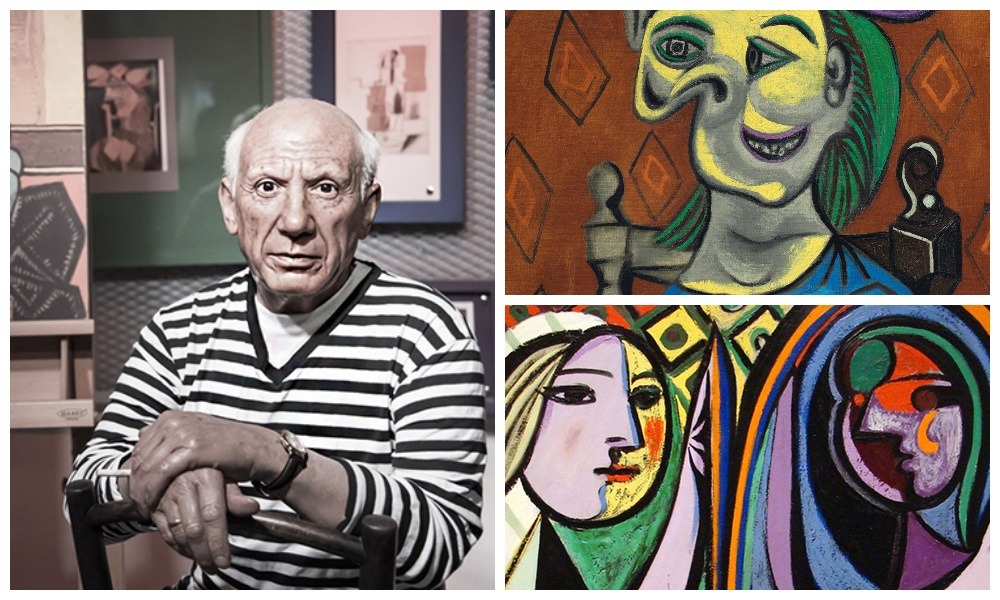

Coen-Solyal realized that during his first 45 years in France, Picasso was stigmatized in three ways: as a foreigner, an anarchist, and an avant-garde artist.

Coen-Solal also discovered how brilliantly Picasso handled this situation, building very strong networks both in France and in the Western world. For example, he chose a very young Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler as his dealer. This is truly remarkable. It was the perfect choice. Kahnweiler understood his masterpiece The Maidens of Avignon [1907] before anyone else and succeeded in promoting Picasso’s Cubist works from the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires to the United States before World War I, making him a wealthy man.

The book is dedicated to the development of the avant-garde at the beginning of the 20th century. In Paris, Picasso was friendly with a group of immigrants. They shared a multicultural background and understood exactly what Picasso was doing during the cubist era. No one in the French art establishment understood his innovations.

Picasso’s alienation also gives a new dimension to his post-1914 art. It was difficult to understand the different aesthetic periods of Picasso’s art, for example, in the field of stage design and as a surrealist painter.

The book also reveals Picasso’s strained relationship with his mother, Maria Picasso Lopez, through hundreds of tender messages between them. Coen-Solal spent years going through all the documents and studying different aspects and periods of Picasso’s art. Of course, by the end of his research, he found Picasso much more convincing.