In a catalogue entry on Vivan Sundaram’s 1966 exhibition in Dhoomimal Gallery, New Delhi, his former teacher at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda (now Vadodara), the eminent artist and pedagogue K.G. Subramanyan, characterises his emergent oeuvre as “the living scene”. Subramanyan addresses Sundaram as a young artist boldly charting a distinctive path that engages with post-independence India’s complex visual culture via “the old hurtling with the new, the naïve and the sophisticated, the sober and the hysterical”.

Soon after this solo debut, Sundaram moved to London to study at the Slade School of Fine Art, where he was mentored by the British-American artist R.B. Kitaj. Activism beyond the classroom and the white cube became a part of Sundaram’s daily credo as he joined efforts to set up a commune for civil rights activists and even managed to get arrested at a certain point during his years in London. Sundaram made an outstanding suite of paintings in 1968, including South Africa and From Persian Miniatures to Stan Brakhage, which reveal his political acuity and experimental depth as he sensed revolutionary ferment in the aesthetic language of contemporary pop, Surrealist grammar and narrative figuration—steeped in the charged atmosphere of student protests, the anti-Apartheid movement in Britain, opposition to the Vietnam War, and Marxist thought.

Vivan Sundaram (left) in front of Glass Mural (1989), at Shah House, Mumbai, with his co-creators of the work Nalini Malani (centre) and Bhupen Khakhar Courtesy of Vivan Sundaram and Sher-Gil Sundaram Arts Foundation

Some of these formative works were displayed in the survey show Vivan Sundaram: Disjunctures (2018) at Haus der Kunst, Munich, curated by Deepak Ananth and conceived by the late Okwui Enwezor. In an email correspondence with me, Enwezor wrote: “The work is never overwrought but considers the vividness of making and the traces of human labour as ways of knowing, but above all it is his consistent and uncompromising exercise in building a vital relationship between art and humanism that enables us to engage the powerful work of a thinker of forms and ideas at the level he has. The rediscovered paintings are the highlight of the show. It is everything I have always hoped to see in the artistic practice of serious artists. You must come see the exhibition.”

In February, Sundaram’s latest endeavour, Six Stations of a Life Pursued (2022), was unveiled at the Sharjah Biennial as part of 30 new commissions selected by Enwezor and Hoor al Qasimi, the director of Sharjah Art Foundation and curator of the 15th Biennial edition. In this sequence of tableaux, a grouping of protagonists donned in black assemble, huddle, lean into one another as if to mark into skin the glowing embers of mourning and folded contours of traumatic memory. Given the artist’s enduring inquiry into mortality, aesthetic freedom and politically resonant narrative-building, it is uncanny but not in the least surprising that this starkly confronting work represents the final offering to his global public.

Vivan Sundaram, One and the Many (2015), made up of 409 terracota figurines © Vivan Sundaram. Photo: Maximilian Geuter. Courtesy of Chemould Prescott Road

Through the 1970s, Sundaram was associated with cultural engagements and civic actions of the Students’ Federation of India and the All India Kisan Sabha, the farmers’ wing of the Communist Party of India. While his close friends and comrades were party members, policy makers and academics, Sundaram chose to remain out of party politics, and yet he was vociferous on issues that impinged on secular values, artistic expression and the communitarian spirit of public life.

Sundaram’s painting People Come and Go (1981) is indicative of this circle of camaraderie, shared inspiration and the worldliness of an artist’s home, as it pictures the artists Howard Hodgkin and Bhupen Khakhar with his friend Vallabhbai in Khakhar’s living room studio. The painting was a highlight at the Festival of India exhibition Contemporary Indian Art at London’s Royal Academy of Arts in 1982, curated by the critic-curator and Sundaram’s life partner Geeta Kapur, and Richard Bartholomew.

A scholarly and artistic lineage

For Sundaram, archiving traces of artistic kinship naturally extended to his own family as he assembled their lineage through photomontages, mnemonic souvenirs and publishing. Sundaram’s maternal grandfather Umrao Singh Sher-Gil was a scholar of Sanskrit and Persian, a yogi and avant-garde photographer. His mother, Indira, was the younger sister of the legendary artist Amrita Sher-Gil, whose life bridged South Asian and European cultural spheres. His sister Navina Sundaram moved to Germany in 1964, where she worked as a prominent television journalist, political editor and film-maker. Their father Kalyan Sundaram was the first law secretary and the second chief election commissioner in the Nehruvian era. Vivan Sundaram was born into this richly talented family, in the hill town of Shimla in 1943, and educated at the Doon School, before his move to university.

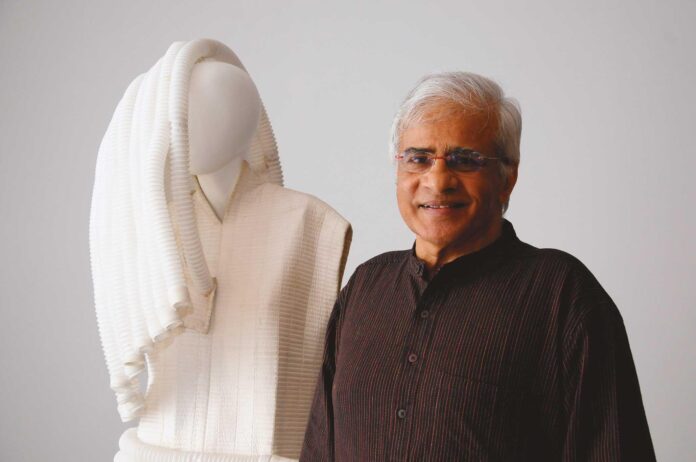

Sundaram at home in Delhi with the art critic and curator Geeta Kapur, his wife of nearly 40 years

As a leading cultural organiser, Sundaram revelled in creative alliances, and this trait never dulled as he spearheaded collaborative models for studio work, discourse and activism. The most recent, and one that continues his family’s artistic legacy, is the Sher-Gil Sundaram Arts Foundation, based in New Delhi. In 1976, he founded the Kasauli Art Centre at his ancestral home of Kasauli in the sub-Himalayan mountain range. Ivy Lodge became a hub for artist workshops, interdisciplinary residencies, experimental productions and generous intellectual pursuits. The economist Prabhat Patnaik recollected in his memorial statement on Sundaram how “the idea of launching a journal was mooted” during a seminar in Kasauli, “which soon became a reality in the form of the Journal of Arts and Ideas. The journal could not be sustained for long, but its few issues bear testimony to the ferment of the times and also to the immense talent in the country”. The second issue, released in 1983, profiles the literary contributions of Gabriel García Márquez. It lists Sundaram as part of the editorial team and profiles a cover and drawing series he composed in Mexico in 1978, accompanying an interview elucidating Márquez’s outlook on the arts, society and dictatorship, translated from Russian.

Installations on a grand scale

When I first got to know Vivan Sundaram and Geeta Kapur in New Delhi in the mid-2000s, it was not just through his exhibitions, but as much through his good-humoured and committed presence at public events of the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust, of which he was a founder trustee. The rise of Hindu nationalism—or Hindutva—in recent decades and the impoverishment of India’s secular fabric troubled him endlessly, while also galvanising distinctive public art endeavours and community-led exhibitions such as Art on the Move, Gift For India and Ways of Resisting: 1992-2002.

Sundaram’s colossal project Memorial, first created in 1993 and elaborated upon over several years, emerged in this vein as a call “against forgetting”. This immersive installation— exhibited as part of Century City at Tate Modern, London, in 2001 in the chapter Bombay / Mumbai: 1992-2001 co-curated by Geeta Kapur and Ashish Rajadhyaksha—and once again on view in the museum’s Tanks section, is reminiscent of an archeological ruin, burial and crime scene. It includes a silhouette of steel barriers and a gateway made of luggage—marking the destruction of the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya in 1992 by right-wing Hindu mobs, a cataclysmic event beyond the scope of singular representation—and a news photograph by Hoshi Jal for the Times of India in January 1993 of an unknown Bombay riot victim slumped in a street corner.

Vivan Sundaram, Gun Carriage and Mausoleum (2014), part of his monumental project Memorial (1993-2014) © Vivan Sundaram. Courtesy of Chemould Prescott Road

The multimedia 409 Ramkinkars (2015), realised at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts in New Delhi in collaboration with the theatre directors Anuradha Kapur and Aditee Biswas and the scriptwriter Belinder Dhanoa, is an epic cycle combining the organic and mechanical aspects of performance centred around the pioneering Bengali Modernist artist and Santiniketan-based pedagogue Ramkinkar Baij. It is another potent reminder of the ways Sundaram invoked facets of cultural history, social biography and labour politics, converging kinetic stage elements, a large cast of actors and lighting into a Gesamtkunstwerk.

At the 8th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art in 2014, the curator Juan A. Gaitán and I worked closely with Sundaram to exhibit works from his series Long Night: Drawings on Charcoal (1987-88) as well as Engine Oil and Charcoal: Works on Paper (1990-91). In a 2019 interview in the White Review, Sundaram said: “The earliest example of my installation work is the Engine Oil series (1991), which references the assault of the US-led coalition forces on Iraq in order to gain control of oil resources. Prior to this I made the charcoal drawings Long Night (1988), which reference the big concrete pillars and barbed wire at Auschwitz. The Gulf War was fought from the air, and this aerial aspect of war pushed me to dismantle the frame.”

In the present climate of war, resource extraction and civic resistance, these series acquire renewed significance. James Baldwin’s words in The Creative Process come to mind when remembering this visionary artist and thought leader: “Societies never know it, but the war of an artist with his society is a lover’s war.”

Vivan Sundaram; born Shimla 28 May 1943; married 1985 Geeta Kapur; died New Delhi 29 March 2023.