Bernd and Hilla Becher, the de facto founders of Germany’s Düsseldorf School of photography, are giants in the history of 20th-century European photography, but they can seem like also-rans in the US museum world, where their better known protégés, such as Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth, have an established presence while the Bechers have been comparatively overlooked. That is set to change this month, when New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art opens Bernd & Hilla Becher, the pair’s first major US survey, featuring around 200 of their works.

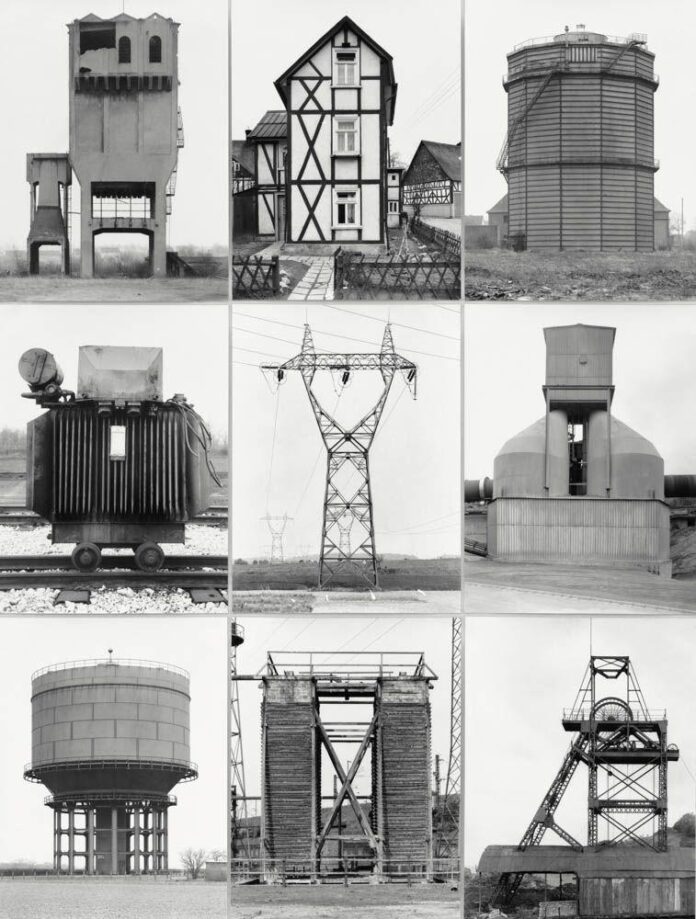

The Bechers, a perennial presence at Düsseldorf’s art academy during the school’s heady post-war heyday, made their mark with what they called “typologies”—austere black-and-white photographs of industrial architecture, generally shot over several decades and then precisely arranged in analytical yet mysteriously elegant grids. The overall goal was to document ignored, even reviled, structures—including blast furnaces, cooling towers, gas tanks and grain silos—but the effect was to synthesise longstanding innovations in photography with newer trends in the visual arts.

Blast Furnaces (1969-93) by Bernd & Hilla Becher © Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher

The images that make up the Bechers’ mature typologies are indeed hyper-refined works of black-and-white photography, recalling the subtle monochromatic palette and compositional rigour of Walker Evans and Eugène Atget. But their unusual display also managed to transcend the photography genre entirely, sharing traits with minimalism, conceptual art and installation art. In 1990, the Bechers, then arguably at the peak of their artistic output, won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale—for sculpture.

The New York show, which will travel later this year to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, presents a number of the pair’s esteemed typologies, including Winding Towers (1966-97), comprising three rows of three photographs of gallows-like mineheads above Welsh coal mines, and their massive, phantasmagoric depictions of blast furnaces, with three rows of ten, shot between 1969 and 1993, in the US, Germany, Luxembourg, France and Belgium.

The discrete perfection of the images belies the immense effort that went into each one, says the Met curator Jeff Rosenheim. The couple wanted “neutral fields”, Rosenheim says, to emphasise the structures’ uncanny shapes. This sent them in search of everything from perfect weather conditions—meaning, for the Bechers, overcast, with minimal direct sunlight—to sustained access to dangerous spots on working industrial sites, in order to accommodate their portrait-like framings of the structures themselves.

The couple’s decades-long persistence in getting just the right shots, under near-daredevil conditions, will be brought into view in the show, thanks to behind-the-scenes Polaroids and journal excerpts.

Bernd Becher’s Eisenhardter Tiefbau Mine, Eisern, Germany (1955-56) Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur—Bernd & Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne.

The exhibition will give a thorough overview of the pair’s mature work, which was formed in close collaboration from 1970 until Bernd’s death in 2007, aged 75. (Hilla died in 2015, aged 81.) But “the revelation of the show”, Rosenheim says, will be examples of their earlier, separate work from the 1950s and early 1960s. Before their collaboration, Hilla was the more experienced photographer, while Bernd was an inspired graphic artist. The show includes largely unknown works such as Bernd’s mid-1950s, near-Romantic sketches of Germany’s Eisernhardter Tiefbau mine in Eisern, south of his birthplace in Siegen, and Hilla’s clear-eyed, neo-Weimar commercial work, such as 1964’s Study of a Steel Thread.

These early works preview what was to come, but some also represent a road not taken, such as Bernd’s vivid watercolour sketch of the Eisernhardter mine—a blue-sky riposte to the couple’s subsequent devotion to shades of concrete-grey.