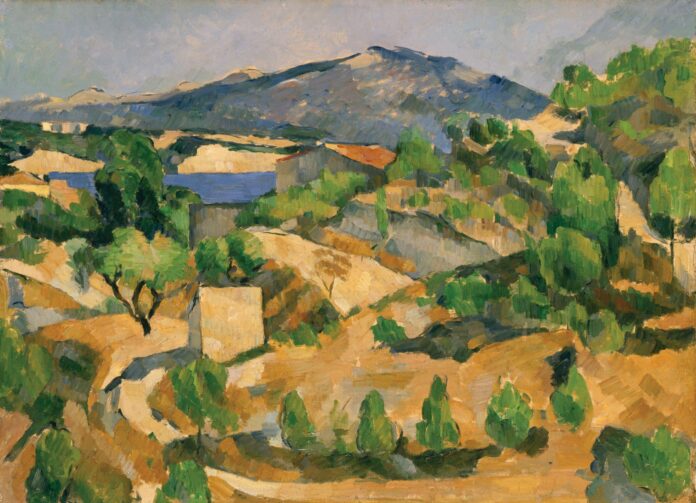

Cezanne, Tate Modern

Until 12 March 2023

Although Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) spent nearly half his life in and around Paris, his heart always remained in Provence. He once wrote of “the links that bind me to this old native soil, so vibrant, so austere”. A new exhibition that opened this month at Tate Modern emphasises the inspiration he found in the landscapes around his birthplace, Aix-en-Provence.

Provençal themes constantly recur in Cézanne’s work: the grounds of the family home known as the Jas de Bouffan; his studio in what was then the outskirts of Aix at Les Lauves; the abandoned quarry of Bibémus with its dramatic rock formations; and, most importantly, distant views of the limestone crest of Mont Sainte-Victoire. The London exhibition has secured international loans of seven Sainte-Victoire oil paintings, from museums in Paris, Basel, Baltimore, Detroit, Minneapolis, Philadelphia and Washington, DC.

Tate Modern’s Cezanne (Tate has dropped the accent to reflect the original Provençal spelling) is the biggest show of the artist’s work in the UK for more than a quarter of a century, with 65 oil paintings and 17 works on paper. This follows its presentation at the Art Institute of Chicago, where it attracted around 190,000 visitors.

One surprise is how many of the works were once owned by fellow artists. These early collectors included Caillebotte, Degas, Gauguin, Matisse, Monet, Picasso and Pissarro. Monet, who once had 14 oil paintings by Cézanne, described him as “the greatest of us all”. Picasso, who spoke of Cézanne in similar terms, bought a plot of land on the slope of Sainte-Victoire to be closer to what the Tate curator Natalia Sidlina calls “his spiritual ancestor”.

Even today, Cézanne remains an “artist’s artist”. Among the lenders to Tate is the Abstract Expressionist Jasper Johns, who is providing three watercolours. As Tate Modern’s director, Frances Morris, explains: “Fellow artists were the first to recognise the value of his iconic and, at the time, seemingly unsophisticated, approach to colour, technique and materials”. She promises the show will “revisit and revitalise Cézanne’s legacy”. M.B.

Installation shot of Frank Auberbach The Sitters at Piano Nobile

Courtesy of Piano Nobile, Photo: David Owens

Frank Auerbach: The Sitters, Piano Nobile

Until 16 December

This show is the first dedicated overview of the German-British painter Frank Auerbach’s portrait heads and includes more than 40 paintings and drawings, ranging from 1956 to 2020. The exhibition explores the special connection between Auerbach and his sitters—the models attending weekly sessions over months, years and decades. Auerbach has said of his paintings that they should meet two criteria: the picture has to be new and it has to be true, seeming both “unfamiliar and crazy” and “banally and obviously like the subject”. S.S.

The Cosmic House, Nan’s Room as a research residency studio.

Photo by Marysia Lewandowska, courtesy of The Cosmic House.

Marysiya Lewandowska: how to pass through a door, The Cosmic House

Until 10 September 2023

A new sound installation by the artist Marysiya Lewandowska will accompany visitors’ wanderings through The Cosmic House, the former home of Charles Jencks, the architectural historian and postmodernist provocateur.

If Charles’s ideas, wit and senses of style and humour are embodied and embedded in this Grade-I listed house (now opened as a museum), Lewandowska made it her mission to revive the voice of Maggie Jencks, a formidable individual who was instrumental in the design of the house and whose name lives on through the Maggie’s cancer caring centres she founded with her husband.

Lewandowska’s work, how to pass through a door, takes the form of sound pieces dispersed through the rooms in the house. One is a recording of a 1988 lecture Maggie Jencks gave on Chinese gardens (her specialist area of research). “That was also,” adds Lewandowska, “the year she was diagnosed with cancer.” This piece permeates the Spring Room, part of Jencks’s programme of a house laid out by the seasons, and looking over the garden that Maggie was instrumental in designing.

The work is the result of a year-long, inaugural residency at The Cosmic House in which the artist questioned the boundaries of the professional, the personal, the cultural and the archival, and the tensions between all of these in the founding of a new public institution. The work sits amid Lewandowska’s practice of digging into institutional archives to recover women’s voices and contributions. These include her project, The Women’s Audio Archive, and her work at the V&A Pavilion of Applied Arts at the Venice Biennale in 2019 (It’s About Time), which used fictionalised voices to focus on the absence of women in art history.

“By placing the voice at the centre of the project, the house will act like a well-tempered instrument accelerating its most recent transition from a former home to its current museum status,” says Lewandowska. “The voice can never be mistaken for another; it forever belongs to a person and beckons its owner into being.” E.H.

Anj Smith’s Misleading Like Lace (2022)

Photo: Alex Delfanne, courtesy of The Perimeter

Anj Smith: Where the Mountain Hare has Lain, The Perimeter

Until 17 December

The show features new works as well as pieces from the collection of Alexander V. Petalas, and marks the first solo presentation of Anj Smith’s work in London since 2015. The idea of the exhibition was, Smith says, a counter to “fast-paced consumption”. Consisting of a pared-back selection of eight paintings and two etchings, the show should allow viewers space to slow down and contemplate the British painter’s otherworldly images. The gallery also invited the spatial designer Robert Storey to create a meditative landscape for Smith’s intricate paintings and allow visitors a moment of total immersion into the artist’s universe. S.S.

Lucian Freud’s Girl in a Green Dress (1954)

© The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022 / Bridgeman Images

Lucian Freud: New Perspectives, National Gallery

Until 22 January 2022

How much is too much? That is the question facing the National Gallery as it launches its blockbuster Lucian Freud (1922-2011) exhibition this month, timed to coincide with the centenary of the painter’s birth. Freud, undeniably, is everywhere; over the past two decades, there have been almost a dozen shows of his work in London alone, including major surveys at the National Portrait Gallery in 2012 and the Royal Academy of Arts in 2019. Last year, Freud was on show at Tate Liverpool, while several smaller exhibitions will run concurrently with the National Gallery’s.

The National Gallery’s Daniel F. Herrmann, who has curated Lucian Freud: New Perspectives, suggests that the gallery is able to move the dial. “His popularity speaks to the quality of his work—people like to see it and there’s a lot to see. But I also feel that a lot of exhibitions show ways of thinking about Freud that have been done before. Now is a great time to reconsider Freud. That is what we are trying to do and what, frankly, we are fortunate we can do as an institution.”

Herrmann’s approach is to reposition a major figure. “Younger artists are interested in his work right now,” he says. “There is a real resurgence in figuration, what it does, how it conveys messages, what it can do. All of these questions intersect with Freud.”

So, what is this new thinking? Herrmann says he admires “how committed Freud is to the practice of painting”, which “comes with a certain amount of radicality”. He continues: “The work requires and rewards radical looking. You learn a lot when you try to figure out how each painting operates.” Freud’s commitment to flesh and nakedness is a key part of it. “It is about truth. Not through simple verisimilitude, photorealism as it were, but veracity—what is the truth of a person? Freud makes the analogy: life is paint, flesh is paint, paint is flesh.”

Sois this exhibition the last word on Freud? Herrmann hopes not. “Freud is one of the best figurative artists in the world and deserves being looked at afresh,” he says. “When people get a chance to reassess what Freud is, I hope it will allow lots of new exhibitions, new questions and new ideas in the future.” A.P.

Ufuoma Essi’s Is My Living In Vain (2022)

Courtesy of the artist

Ufuoma Essi: Is My Living in Vain, Gasworks

Until 18 December

Gasworks presents a new film commission by London-based filmmaker and artist Ufuoma Essi. Is My Living in Vain has been produced through the use of archive footage drawn from VHS tapes and YouTube clips coupled with on-location 16mm footage and a soundscape of oral histories. The film is a meditation on the continuing history and emancipatory potential of the Black church as a space of belonging, affirmation and community organising, with a focus on congregations in west Philadelphia and south London. S.S.

Helen Saunders’s Hammock (1913-14)

The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust) © Estate of Helen Saunders

Helen Saunders: Modernist Rebel, Courtauld Gallery

14 October-29 January 2023

The angular figure in Vorticist composition (Black and Khaki) (around 1915) by Helen Saunders bursts out of the barrel of a gun. Unlike some of the pre-war examples of Vorticism—a short-lived but explosive British take on Cubism and Futurism—it seems to evoke the human cost of mechanised warfare rather than glorifying it.

Saunders was one of only two women in the Vorticist group alongside a dozen male artists, including its founder Wyndham Lewis, Jacob Epstein and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. The movement’s main output was two group shows, one in London, one in New York, and two issues of the magazine, Blast. Saunders was included in both shows and had her work and writing featured in the second edition of the magazine, which she distributed from her home in London’s Chelsea. (Her surname appeared as “Sanders” in an apparent bid to spare her family any social embarrassment.)

Vorticism fizzled out as the carnage of the First World War became a reality, the romance of mechanisation receded and many of its members were recruited to the war effort, including Saunders, in an office role, and notably Gaudier-Brzeska, who wrote a piece from the trenches for the second edition of Blast shortly before being killed.

Born in 1885, into a well-to-do family in Ealing, Saunders studied art at the Slade and the Central School of Arts and Crafts, and exhibited alongside artists from the Bloomsbury Group, including Roger Fry, Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell.

Although Saunders continued to make work after the war, she took a step back from the art world in a kind of “self-imposed isolation”, according to her descendant, Brigid Peppin, “rejecting professional groupings”. She continued to make work, but in a style harking back to the Post-Impressionists that she admired, in particular Paul Cézanne. The French artist painted several landscapes around L’Estaque, in the south of France, and four watercolours from the 1920s made when Saunders visited the village are in the show, including a geometric painting of Cézanne’s house.

The 18 works in this small show remained in Saunders’s family after her death in 1963 before being donated to the Courtauld in 2016 by Peppin. There have been few exhibitions of the artist’s work since the end of the First World War, a notable exception being a survey at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum in 1996. “The disappearance of much of Saunders’s early work and the dearth of biographical information has hampered research and obstructed arguments for the artist’s centrality to the Vorticist project,” writes the art historian Jo Cottrell in the catalogue. But recently there has been renewed interest, with her work being included in two group shows: Radical Women at Chichester’s Pallant House Gallery (alongside her fellow female Vorticist, Jessica Dismorr) in 2019; and last year’s Women in Abstraction at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. J.S.

British Museum © The Trustees of the British Museum

Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt, British Museum

13 October-19 February 2023

A major exhibition opening today at the British Museum offers a tale of loot, bitter scholarly rivalry, sex and magic. Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt has as its centrepiece the Rosetta Stone, one of the world’s most famous museum objects, and explores the race between French scholar Jean-François Champollion and English polymath Thomas Young to decode its ancient symbols. Meanwhile, conservators will work during the exhibition on ‘The Enchanted Basin’ sarcophagus, believed for centuries to be a magic bath curing the pains of love; the British in Egypt later built a venereal disease hospital on the spot where it was found. The exhibition will include loans from many international museums and scholarly institutions—but none from Egypt. The peppery former Egyptian antiquities minister Zahi Hawass has used the exhibition as an opportunity to demand the return of the Rosetta Stone; its story is not over yet. M.K.