Whether or not you know the life and work German-Venezuelan artist Gego (1912–1994) may depend on where in the world you call home. The deeply influential artist—best known for her conceptual and elegant wire sculptures—has routinely been hailed as one of the most influential figures of post-war Latin American art. In the United States, particularly, however, her recognition has been slow-coming when compared to the fame of her contemporaries. “Gego: Measuring Infinity” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the artist’s first major museum retrospective in the United States since 2005, aims to rectify this discrepancy and introduce Gego’s work to a broader American audience. On view through September 10, 2023, the exhibition presents a simultaneously chronological and thematic survey of her work and practice, offering insight into her distinctive approach to abstraction and influential artistic innovation.

Installation view of “Gego: Measuring Infinity” (2023). Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

Who was Gego?

Born Gertrude Louise Goldschmidt to a secular Jewish family in Hamburg, Germany, in 1912, Gego (a sobriquet used throughout her career using the first two letters of her first and last name) did not begin her career as an artist. She studied at the University at Stuttgart (formerly the Technische Hochschule Stuttgart) under German architect Paul Bonatz, earning a degree in architecture and engineering in 1938. While at university, she was exposed to a variety of art and design movements and trends including those produced by the Staatliches Bauhaus, the leading school and eponymous architectural style that flourished in the interwar period.

During this time, Gego was witness to the Nazi party’s ascension to power, the dramatic rise of antisemitism, and Adolf Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor of Germany. Increasingly throughout the 1930s, anti-Jewish laws and legislative persecution of Jews made remaining in Germany untenable. Gego’s German citizenship was nullified in 1935, and the same year as she graduated the German Reich Ministry of Interior began formally restricting the freedom of movement of Jewish people. Compelled to leave the country, many of Gego’s family members were able to flee to England, however, she was unable to obtain an English visa. Instead, in 1939, she immigrated to Venezuela, where she established herself in the capital city of Caracas.

Unfamiliar with the country, culture, and language, coupled with the fact that she was a woman and nonnational, Gego’s opportunities were often few and far between. Regardless, she was able to use her educational background to undertake work as a freelance architect and designer for several firms. At one such firm in 1940, she met urban planner Ernst Gunz. The pair were married that same year, and they went on to have two children. For a brief period, they operated a furniture studio and shop for which Gego worked as a designer. In 1948, however, Gego returned to working on architectural projects, and in 1951 the couple separated. The following year, Gego met graphic designer Gerd Leufert, with whom she would spend the rest of her life. Coinciding with this, Gego left her architecture practice behind and devoted herself to making art.

Installation view of “Gego: Measuring Infinity” (2023). Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

Line, Form, and Space

Undoubtedly greatly influenced by her professional and educational background in architecture, Gego’s oeuvre is an enduring testament to her exploration and mastery of line, form, and space. Some of the artist’s earliest works, many of which took inspiration from the natural landscape of Venezuela, illustrate her immediate interest in the formal elements of artmaking and familiarity with prevailing artistic trends of the time, including geometric abstraction. Featured on the first ramp of the Guggenheim exhibition, her watercolor, tempera, and gouache paintings feature vibrant, lush vignettes and her first experimentations with variable composition techniques. Also included are early prints and ink drawings, showing a burgeoning fascination with the possibilities of line—predecessors to the three-dimensional works she commenced making in 1956.

Compared to the airy, kinetic sculptures Gego later became recognized for, the early series of sculptures from the 1950s and ’60s on view are visually (and presumably literally) heavy. Largely comprised of painted iron rods and bars, these early sculptures exemplify the artist’s preoccupation with the interaction of line and space, and an ongoing investigation into the possibilities of different geometric forms. Shapes ranging from squares to tetrahedra, comprised of repeating metal lines, overlap, merge, and stagger and space, offering a different visual understanding of composition based on perspective.

Both sculpture and printmaking remained stalwart facets of Gego’s practice, and the evolution of her work can be traced through her use of line. Initially favoring parallel lines in repetition, as she further explored their potential for interacting with space and form, her lines began to intersect and be overlaid in increasingly complex manners—both in her two- and three-dimensional work.

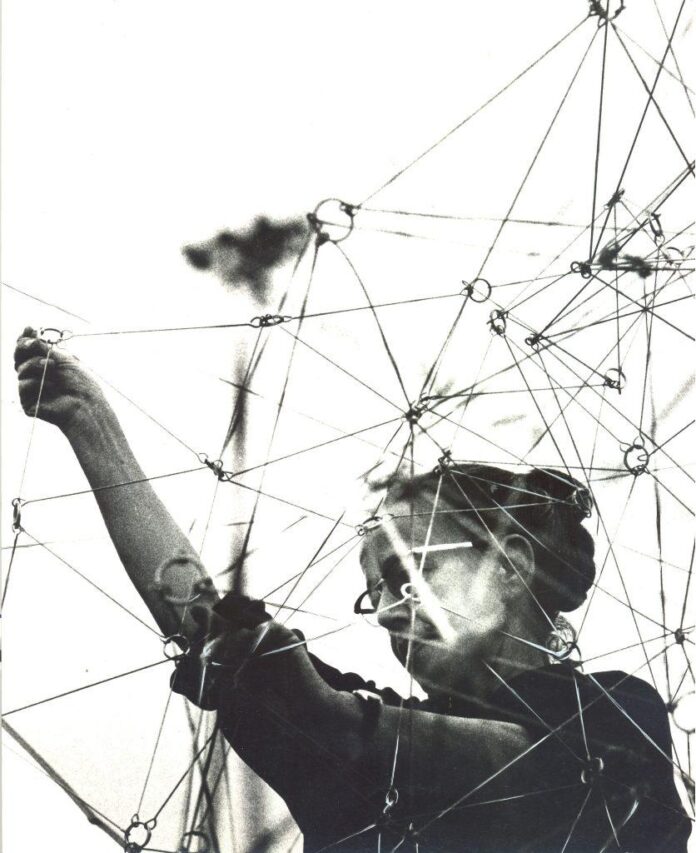

Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt), , 1966. Colección Fundación Gego, Caracas. © Fundación Gego. Photo: Carlos Germán Rojas. Courtesy of Archivo Fundación Gego.

Tamarind Studio, “Drawing Without Paper,” and “Reticulárea”

In both 1963 and 1966, Gego was invited to the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles, where she assumed a comprehensive exploration of the print medium, which resulted in some of her most significant print works. Examples of her experiments into various printmaking techniques, including engraving, etching, lithography, and even embossing, highlight her mastery, as well as exhibit her refined and disciplined approach to color and composition. The Tamarind period prints further emphasize her meticulous investigations into line and shape within the confines of the medium.

In 1969, there was a pivotal shift in Gego’s work, when she moved away from parallel lines to what she termed “reticuláreas,” reticular shapes that resembled nets or structures comprised of nets in her two-dimensional work. This shift soon appeared in her sculptural work as well and subsequently led her to use lighter, more easily manipulated materials such as wire (rather than iron or steel rods or bars). The change in approach is made manifest in pieces from her largest sculpture series, produced between 1976 and 1988, “Dibujos sin papel (Drawings Without Paper).” Here, wire took the place of drawn line, and with each handwoven sculpture hung in proximity from a wall, the wire resembles graphite or ink, and further light cast on the works casts shadows that add another dimension to the work. In a piece from 1985 within the Guggenheim exhibition, the addition of a thin line of red along the edge of the wire grid brings to mind standard graph paper, with a warped addition of gridded wire mimicking a volumetric drawing.

Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt), (1985). Private collection. Photo: Barbara Brändli. © Fundación Gego.

Foremost in her use of “reticuláreas,” her hanging sculptures made up of interwoven and repeated webs of wire capture her pursuit of line, form, and space most succinctly, and are widely considered Gego’s most famous works. From comparatively simple and petite constructions to large scale, room-spanning installations, these sculptures have a penchant for moving with the ambient air within the spaces they are exhibited. Within Gego’s body of “reticuláreas” sculptures, the artist created various individual series inspired by nature—recalling the influence of nature seen in her earliest paintings—such as and .

Gego (Gertrude Goldschmidt), (1976). Private collection. © Fundación Gego. Photo: Tomas R. DuBrock. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Gego’s Enduring Legacy

Considering Gego’s work and practice within the art historical canon, her career and practice can be recognized as an indispensable facet of 20th-century art. Though just over a decade his junior, her work and innovation within the realm of kinetic art are in many ways a formal counterpart to and furtherance of Alexander Calder’s iconic hanging mobiles. Within the context of 20th-century South American art, her experimentations with kinetic sculpture can be seen echoed in work as Brazillian artist Lygia Clark’s reticulated “Bicho (Critter),” or fellow Venezuelan artist Jesús Rafael Soto and Alejandro Otero, emphasizing the importance of the formal aims she pursued in her practice. Though she received widespread acclaim in her lifetime and has maintained name recognition throughout much of the world, her life and oeuvre are primed for renewed recognition in the United States.