When Diego Cortez died in the summer of 2021, the art world choked up. An artist, curator, adviser, and co-founder of the legendary Mudd Club in Tribeca, he had been a ubiquitous presence in downtown New York art and music circles since the 1970s.

Friends described him as “a brilliant visionary,” a “great impresario,” “a charismatic guy,” “always generous,” in a tribute published by the . Those reminiscing about his exploits—and their shared nights at the Mudd Club, summers in Capri, lunches at Da Silvano—included Julian Schnabel, Francesco Clemento, Brian Eno, and Laurie Anderson. Artist Luigi Ontani called Cortez “the master key for every context, situation, day & night, between art, music, clubs, culture, poetry.” (The , for its part, ran a glowing, 1,100-word-long obituary.)

Musician Laurie Anderson and curator Diego Cortez attend The Kitchen Spring Gala Benefit 2013 in New York City. (Photo by Cindy Ord/Getty Images)

The artist who was the keystone of Cortez’s reputation, however, was Jean-Michel Basquiat. He brought the charismatic prodigy to public attention in “New York/New Wave,” the seminal exhibition that he curated at P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center in 1981—an act that has secured Cortez’s place in art history. After Basquiat’s death in 1988, the curator served on the artist’s authentication committee until it was dismantled in 2012. The association with Basquiat made Cortez famous, and admired.

But there was another, darker side to Cortez that was an open secret among his friends, something they knew well but never spoke of publicly—until now.

“The thing about Diego is that he was such a contradiction,” said the musician Arto Lindsay, 70, a fellow Basquiat intimate whose decades-long friendship with Cortez ended abruptly in 2017. “He was so generous, and also a thief. And he often stole from the same people he was generous to.”

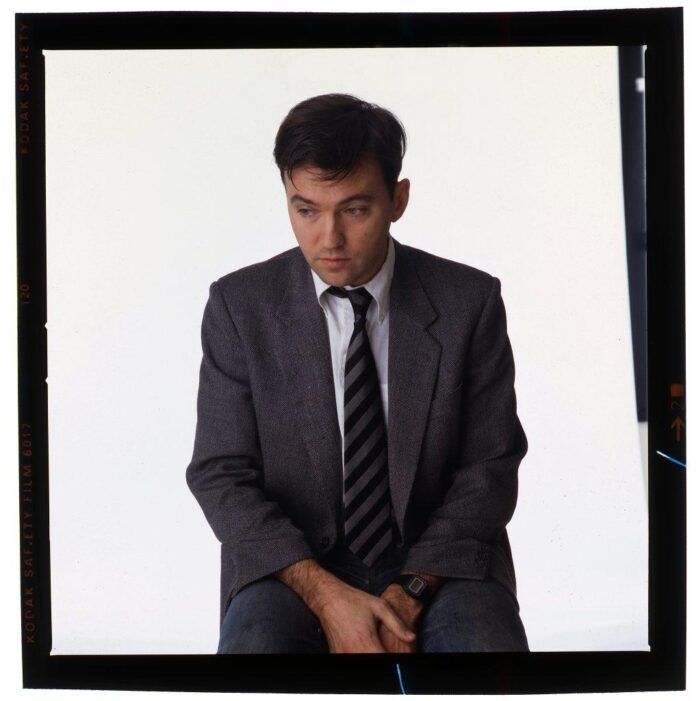

Diego Cortez, 1982. Portrait by Gilles Tapie commissioned by Seth Tillett. Courtesy: Seth Tillett

As I began researching Cortez’s past, these kinds of stories came up again and again, forming a pattern: that Cortez double-dipped on art transactions; that he borrowed money and never paid people back; that he sold works that didn’t belong to him. He was a bully. He authenticated artworks that turned out to be fakes. He would do anything for money when he needed it. “Lock up the art!” one friend would instruct his wife before Cortez came to visit. “We all love Diego, but don’t do business with him,” another person would warn others.

His sister Kathy Hudson declined to comment when I reached her by phone.

But three former close friends of Cortez, Lindsay included, were willing to talk—and what they said opens a Pandora’s Box. Years after the events took place, each is still grappling with a difficult question: How could someone so close to them have betrayed them so heartlessly?

Early Friendships

The first thing to understand about Diego Cortez is that Diego Cortez was not his real name. Born James Curtis in Geneva, Illinois, in 1946, he had adopted the catchy in 1973, the year he moved to New York, as a way of sculpting a new life for himself.

“We all took our own names,” said artist and filmmaker Seth Tillett, 67, who was 20 years old when Cortez picked him up at Barnabas Rex, a Tribeca bar popular with artists. Briefly Cortez’s lover and then the co-owner of a New York gallery with him, Tillett himself went by Doctorovitch, S. Neto, and Fabio. “It was kind of Warholian. We invented ourselves.”

Leisa Stroud, for her part, was 17 when she met Cortez in 1977. The daughter of Black figurative painter Dick Stroud, she was a head-turning beauty in the predominantly white art world and acted as a frequent model for the artists of her generation. Stroud sat for Basquiat, Francesco Clemente, Larry Rivers, and so many others that Cortez once suggested organizing a “Leisa Show” of the portraits, she told me. (It never materialized.)

Jean-Michel Basquiat painting his first solo show in the cellar of the Annina Nosei gallery, 1981. Photo: Seth Tillett

What unites Stroud, Tillett, and Lindsay is something almost magical: because of their friendships with Basquiat, the artist gifted each of them drawings over the years—everything from tossed-off sketches to portraits to flights of fancy—that would come to be worth a fortune. Another thing that unites them? Cortez knew about the artworks and, by hook or by crook, took possession of them, they say, selling them without their knowledge or permission and then paying them a small fraction of the money he owed them.

“I don’t think he sold those drawings to screw me over,” Stroud, 63, said of her own experience of Cortez selling artworks entrusted to him. “I think one thing led to another. He sold them and he ended up keeping the money for himself because he needed it at that time and he probably thought, ‘Oh, I’ll pay her back later.’ And then he couldn’t backtrack, so he just cut me out like I was never there. It was easier for him not to think about me.”

Tillett, along with Lindsay and Stroud, said they have never before spoken out negatively about Cortez in public. In fact, no one has. He was so important to so many people throughout their careers that no one wanted to cross him while he was alive.

Some may have remained silent because they felt they owed him. Cortez could give a friend an artwork by Walker Evans, pay for plane tickets and dinners at Masa, a Michelin-star restaurant in Manhattan, or have friends and their families stay at the villa in Capri he rented every summer, Tillett said. Or he would dangle the possibility of an exhibition or commission.

“But then the bill would always come due when people were most vulnerable,” Tillett said. “And he’d take everything they had.”

An invitation to “Sketchbook for Arto,” an exhibition of the notebook Jean-Michel Basquiat left for Arto Lindsay.

Several people I contacted for comment seemed angry about my line of inquiry. They refused to speak and tried to discredit (and even intimidate) Tillett, Lindsay, and Stroud. “They are riffraff,” one person said. “You can’t trust everyone to tell the truth,” another wrote.

But Stephen Torton, who worked as Basquiat’s assistant and was a friend of Cortez, said the stories were consistent with Cortez’s slippery character and propensity for lies, which was as well known as his charm.

“There’s no doubt in the community about that,” he said from Paris this week. “He was flamboyant and dishonest and brilliant in equal measure. The art world was small in the 1980s and Diego was the neighborhood rogue.”

Struggling to reconcile the Jekyll-and-Hyde-like contradictions, Tillett said: “I wonder if Diego had a pathological side?”

Bad Behavior

The scale of Cortez’s bad behavior—and potentially his late-life desperation—became apparent to many of his friends when the news broke, after his death, about the fake Basquiat paintings at the Orlando Museum of Art. That group of artworks was personally authenticated by Cortez between 2018 and 2019, after he left New York and could barely make ends meet.

“Anyone with any knowledge of Basquiat’s work would know they didn’t look like Basquiat at all,” said Lindsay. “Diego would know they were bullshit. He did something really low.”

After opening with a bang of publicity, the show was shattered when the FBI raided the premises and confiscated the art. The aftermath was swift: the museum fired Aaron De Groft as its director and chief executive, and the United States attorney’s office charged the 45-year-old former Los Angeles auctioneer Michael Barzman—along with an accomplice identified only as J.F.—with creating the series of Basquiat forgeries.

“Untitled (Self-Portrait or Crown Face II),” the work allegedly painted in acrylic, wax crayon and paint stick on the back of FedEx shipping material. Via Orlando Museum of Art.

What made Cortez authenticate the forgeries? It’s hard to know for sure, but people who knew him believe it was a result of a reversal of fortune.

For many years, Cortez led a “princely life,” Lindsay said. He would rent the villa in Capri during the summers. He lived in a large Chelsea loft in a building that was once owned by artist Sandro Chia and where Larry Gagosian opened his first New York gallery.

He bankrolled his lifestyle with art dealing and advising several wealthy clients, including the collectors Gerald Fineberg and Michael Salke in the U.S. and the Benneton family in Italy.

“He helped us build a wonderful collection,” said Salke, adding that he worked with Cortez from 1993 until his death and never had any issues with him. “He made available works for us that we could never have bought at other places.”

But some business relationships soured as a result of accusations that Cortez misused funds and charged fees on both ends of the deals without alerting his collector-clients, according to people familiar with these details.

Installation view of the “Heroes & Monsters: Jean-Michel Basquiat, The Thaddeus Mumford, Jr. Venice Collection” at the Orlando Museum of Art, 2022. Courtesy of the OMA.

Asked if Cortez got more than one commission on the same transaction—an unethical business practice—while working with him, Salke said, “Even if he did, it didn’t affect me. An auction house does it to me all the time.”

Fineberg, a real estate mogul who died last year and whose collection was recently sold at Christie’s, made Cortez pay him back by forcing the sale of his loft, according to two people who knew both men. Property records show that Cortez—under his legal name James Curtis—sold the apartment to Fineberg for $1.9 million in 2006. Curiously, Fineberg quickly resold the apartment to Michael Black, who became his art adviser after Cortez.

The truth about Cortez’s business dealings will likely never be known. There are conflicting accounts. Tillett said that Cortez told him he had lost all major clients, including the Salkes and the Finebergs, had no money left and no one to sell art to. Ultimately, Cortez left New York in 2015, his financial situation deteriorated, and broken friendships in his wake.

Diego and Leisa: Betrayal

Leisa Stroud first became friends with Basquiat in 1978.

“We were kind of like brother and sister,” she said. “There weren’t many Black people in that scene and we could identify with each other a lot.”

In 1981, just as the artist’s star began to rise, Stroud moved to Culebra, a small Caribbean island, to make beautiful liquid pigment paintings on silk. Over the next two years, Basquiat came to visit, escaping his overnight success. She often modeled for him on the beach, and he left her many of these portraits along with other large works on paper depicting her life amid dogs, cows, and roosters.

After Basquiat’s death, she began selling these drawings to make ends meet—for $1,000 to $5,000 each. She was a single mother. Cortez was a godfather to her first daughter and the first person to hold her second, she said. When she moved to Rhode Island, Cortez was a frequent guest, later renting an apartment nearby and coming summer after summer for about a decade, she said.

Photo of artist and model Leisa Stroud and American art curator and artist Diego Cortez (born James Curtis), 1979. (Photo by Marcia Resnick/Getty Images)

So Stroud didn’t think twice when years later Cortez asked to borrow six pencil drawings by Basquiat to decorate his loft in Chelsea ahead of a potential client’s visit. They were among just 10 works by Basquiat she had left.

“I didn’t have them hanging on my walls,” Stroud said. “They were put away in a portfolio. I didn’t think there was any downside. I wanted to help him out.”

A year went by. Then one day she heard a voicemail on her answering machine. It was Cortez telling her matter-of-factly that he sold her drawings. “You’d be happy with the money I got,” she recalled him saying. It was around $100,000. He notified her that he’d take a percentage and send her a check for $40,000, with the rest of the amount coming in 30 days, she said.

“I literally lost my breath,” Stroud said. “They weren’t his to sell. At the time I was broke but I didn’t plan to sell them. It took me weeks to get him in person on the phone. I told him he had to get the works back. He said there’s no way he can get them back. He sold them to someone in Italy.”

She received the $40,000 check—then never saw another penny. Cortez blamed it on the crash of the Italian stock market, saying the buyer could no longer pay. Unable to afford a lawyer, Stroud turned to her successful artist friends, asking for help. “No one wanted to get involved,” she said.

Soon, Cortez stopped responding to her calls. It was 1998 and their 20-year friendship was over in the blink of an eye, she said.

“I knew he’d taken advantage of people business-wise,” she told me. “I knew he did shady stuff. He fudged things. I could never imagine he would do that to me. I felt we were related. I always thought I’d get a call or a letter in the mail. He just cut me off completely.”

Today, she doesn’t know what hurts more: Losing one of her closest friends or being robbed by him of the money that would have helped her raise two children while fighting for her life as she waited for liver transplant surgery.

Diego and Arto: Shattered Trust

Around 1981, Arto Lindsay remembers, he and Basquiat spent a week crashing at a friend’s apartment in the East Village. Afterwards, Basquiat left him a notebook with 22 pages of drawings and poems he made.

A legend in music circles, Lindsay never made much money. The notebook was Lindsay’s most valuable material possession—his “nest egg,” he told me this week from his home in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. “I just stashed it away in a drawer forever and ever.”

Then in 2011, he pulled it out of the drawer to showcase in an exhibition at AS IF Gallery that Cortez, Tillett, and his partner Nicole Rauscher set up in Harlem. It was a noncommercial affair, with monthly exhibitions and communal dinners for 50 people. The show was titled “Sketchbook for Arto” and drew a motley crowd that included music legend David Byrne and the writers James Fenton and Darryl Pinckney. Lindsay sang and played the electric guitar.

Arto Lindsay performs at the opening of “Sketches for Arto” at As If Gallery. Courtesy: Seth Tillett

After the show closed, Cortez held onto the notebook along with other works from Lindsay’s collection. A couple of years later, Lindsay mentioned to Cortez that he was thinking of selling the notebook to set up a fund for his son’s education.

“I didn’t have anything to leave to my son except these drawings,” he said this week. Since Lindsay and Cortez had previously curated a show for Luhring Augustine, Lindsay suggested approaching the gallery to sell the notebook.

“He said, ‘No, no, no,’” Lindsay recalled. “Shortly thereafter, he told me he sold it for $200,000.”

Lindsay said he was shocked. He never gave Cortez permission to sell the notebook. They never discussed any details, he said. Cortez promised to pay Lindsay in four installments of $50,000 and sent the first check, the musician said.

Soon, more bad news followed. Cortez notified Lindsay that the IRS had confiscated the balance of $150,000 from his bank account, according to a 2012 email viewed by the Art Detective. “I have been scrambling to recover this $ for you and it has been a nightmare,” Cortez wrote.

Initially, Lindsay was hopeful he would be made whole. After all, Cortez was a close friend, collaborator, frequent travel buddy. After Lindsay was diagnosed with leukemia in 2005, Cortez helped raise more than $100,000 for his treatment. There was trust.

But years went by, and no money came. Cortez never told him who bought the notebook. Finally, in 2017, Lindsay cut all ties with Cortez. On his deathbed, Cortez reached out asking for forgiveness, Lindsay said.

“I hope you can find some peace,” he told Cortez.

Lost and Found

Tillett had his own version of this story. In the late 1980s, he told Cortez that he got a $10,000 offer for drawing Basquiat gave him. Cortez urged Tillett to sell it to him for $5,000, and when he refused, Cortez told him, “Seth, learn: Friendship can be used to help people and it can be used to harm people.” The younger man sold the work for $10,000 and cut ties with Cortez for a while before rekindling their friendship.

After Tillett found out what Cortez did with Lindsay’s notebook, he ended the friendship for good. They never spoke again. But because he was a partner in the AS IF Gallery, he also felt responsible. The injustice of the situation haunted him.

Every now and then he would search the Internet in hopes the notebook would come up. He was hoping if he found the person who bought them, somehow amends could be made. Last year, he spoke with a curator of an exhibition called “Seeing Loud: Basquiat and Music,” a collaboration between the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and the Musée de la musique–Philharmonie de Paris. The curator mentioned that the show would include a group of drawings, titled

Diego Cortez, left, and Seth Tillett, right, at As If Gallery. Courtesy: Seth Tillett

“The last time I saw them was in a vitrine in my gallery,” Tillett said. “I called Arto, screaming, ‘I found them! I found them!”

He also found out that the notebook, now titled , was lent to the shows by the Enrico Navarra Gallery in Paris, whose late founder was a major Basquiat dealer and published the artist’s catalogue raisonné. (A gallery representative confirmed that it bought from Cortez but didn’t respond to calls and emails seeking further details.)

The discovery of the notebook and its owner renewed Tillett’s hope that Lindsay could be finally made whole after all these years. That hope is Quixotic at best—something Tillett is well aware of.

How would it happen? Doriano Navarra, who took over the gallery after his father’s death in 2020, could do “the right thing” by selling the notebook and sharing some of the proceeds with Lindsay, Tillett says. Effectively, he wants a complete stranger to treat Lindsay with more decency than his close friend had.

“There is a chance, however remote, of reversing one and only one of Diego’s devastating, life-altering ripoffs of his ‘friends,’” said Tillett. “Navarra can undo the effects and convert the shame of having been tricked into an unauthorized acquisition. And they can recover every centime.”

Somewhere, is Cortez laughing?