Entering the first gallery of Fotografiska’s “Hip Hop: Conscious, Unconscious” exhibition, it’s hard to imagine the array of black-and-white photographs, each documenting stark New York City street scenes, as containing the seeds of a globe-dominating cultural behemoth.

But they do. In between the images of kids cradling boomboxes in deserted lots, of youths manning turntables in the street, and of young street gang members play-fighting in a Bronx basketball court—variously shot by photogs including Jean-Pierre Laffont and Henry Chalfont—are captured the essence and energy of a subculture formed in response to and in spite of a bleak urban landscape.

“We weren’t thinking about hip-hop as a thing beyond something that we did,” Sacha Jenkins, the exhibition’s co-curator, told Artnet News of hip-hop’s dawning. “It wasn’t an industry, it wasn’t a clothing line, it wasn’t a fancy handbag—it was just kids.”

Installation view of “Hip Hop: Conscious, Unconscious” at Fotografiska New York. Photo courtesy of Fotografiska New York and © Dario Lasagni.

For Jenkins and his co-curator Sally Berman, tracing the genre’s 50-year history in an exhibition meant illustrating a trajectory, per the show’s title, from that unconsciousness to consciousness, when hip-hop emerged as a commercial phenomenon at the close of the 20th century.

In its following galleries, “Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious” unfolds with increasingly slick portraits of hip-hop stars not limited to Lauryn Hill, Queen Latifah, Tupac Shakur, the Beastie Boys, and Kendrick Lamar. They’re images that see the cementing of hip-hop codes, as practitioners awoke to the genre’s form and impact, as much as the solidifying of an American visual culture.

Campbell Addy, Megan Thee Stallion posing for The Cut (2022). Photo courtesy of Fotografiska New York and copyright of the artist.

Jenkins himself has had a front row seat to this transformation. He was exactly one of those kids who partook in the scene, documenting early graffiti art in his pioneering zine, Graphic Scenes & Xplicit Language, in the late ‘80s. A long career in publishing followed, during which he co-founded the hip-hop journal Ego Trip in 1994, served a stint as music editor for Vibe, and published 2008’s Piecebook, the essential insider’s guide to graffiti art history. His unparalleled knowledge of graffiti culture, too, earned him a fellowship at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism in 2000.

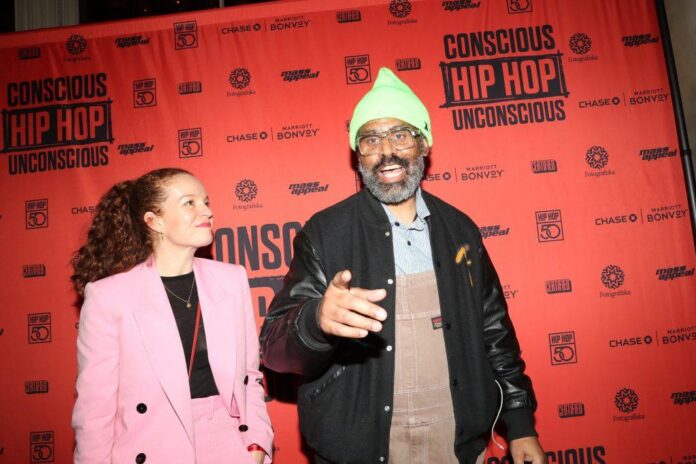

Currently the chief creative officer of urban culture platform Mass Appeal, which partnered with Fotografiska for the exhibition, Jenkins shared with Artnet News the thinking behind the show, and his first-hand view of hip-hop’s evolution and enduring footprint.

Janette Beckman, (1990). Photo courtesy of Fotografiska New York and copyright of the artist.

How did you and your co-curator Sally Berman start to approach distilling 50 years of hip-hop photography into an exhibition?

In thinking about the show, I wanted to find a way to break down 50 years of hip-hop in a way that’s interesting and relevant, and that starts the conversation. I wanted to start with the time when we weren’t thinking about it since it was such a natural form of expression for many of us, before it turned a corner and we became conscious of ourselves and started to understand the power in what it was that we were creating. That understanding coupled with commerce has led to where hip-hop is, as I like to refer to it, as a language, a global language.

Could you expand on the “unconscious/conscious” dichotomy of the exhibition’s title? How does it reflect hip-hop’s trajectory?

We wanted to make sure there was a balance of everyday people who were not necessarily celebrities or superstars, but were people who were of the culture. Because if you have no culture, you have no superstars, right? And then the other side of it speaks to the evolution of the music and the music industry. You go from these really simple, humble photos to music videos that people spend a million dollars on. So you can kind of see the evolution of hip hop through the photographs, but before that, you see the culture flourishing in its natural habitat.

Josh Cheuse, Run DMC’s feet under the table at The Fresh Fest press conference (1985). Photo courtesy of Fotografiska New York and copyright of the artist.

How do you see the process of hip-hop becoming codified in visual culture—its “conscious” chapter?

I think the consciousness comes from understanding economic power and cultural influence. In the ‘80s, rich people never really put value in their sneakers. And now, you have this world of footwear and sneakers where kids wait in line for three days, and a pair of sneakers could sell for thousands of dollars. It was hip-hop—hip-hop consciousness and hip-hop’s aesthetic—that created that value, that created that industry, that created that sensibility.

I think when that hip-hop mentality and sensibility crossed over culturally, through fashion, through language, through media, that’s when this understanding of hip-hop’s power crossed over into the world of the people who created it and who weren’t necessarily capitalizing off of it. It wasn’t until generations later when the value of hip-hop was really understood, when entrepreneurs started to make lots of money and have complete control over how they are represented in the world.

You were involved in the early graffiti art scene as it was happening in the ‘80s, particularly with your zine-making. What about it made you eager to document it?

It’s one of the “elements” of hip-hop that I was most active in. By the time I was 16, I was still interested in it. Most of the kids in my neighborhood were out of it actually; drugs came into play. I remember still being into graffiti and there were kids in my neighborhood who were selling crack and who were like, “You still doing that graffiti thing?” These kids are making, you know, $2,000 a day in 1987, but I stuck with it.

I felt like I was finally able to find a way to be more productive and contribute something to the culture in a way that I wouldn’t get arrested. I found that making a zine was the best way to do that.

Installation view of “Hip Hop: Conscious, Unconscious” at Fotografiska New York. Photo courtesy of Fotografiska New York and © Dario Lasagni.

What in your view was graffiti art expressing that has made it the force it is now?

I think it’s the DIY aspect that young people can really connect to—you can just pick up a can of paint and do your thing. The days of doing illegal graffiti, I think, for a lot of these kids today, doesn’t necessarily register because there are cameras everywhere and the penalties are stiff. But they’ve been able to see guys who have come out of that culture who now design video games and who have clothing lines. You see a guy like Futura 2000, who started writing graffiti in 1973—look at where he is today, at 67 years old. It’s pretty amazing what the power of the aerosol can has done for so many people. I just think it’s very accessible, it has the right energy that young people are attracted to, and yeah, it looks cool.

What do you make of hip-hop at this end of half a century?

Today’s hip-hop shouldn’t be for me, because there are so many things that young people still need to learn that I’ve already learned in hip-hop. I can go back and listen to all the albums I loved and find lessons. That would have been useful to me when I was in my teens or 20s. But those same lessons being broadcast by some 21-year-old kid now has no relevance to me because I’m a grown ass man. It should be for a new generation of people who are going through whatever they’re going through at the moment.

That’s why hip-hop is a very important and powerful medium that transcends generations. People continue to reference it as a way to exorcize their demons or to exorcize their minds. I love hip-hop to death, and I’m so happy that so many other people feel the same way.

Installation view of “Hip Hop: Conscious, Unconscious” at Fotografiska New York. Photo courtesy of Fotografiska New York and © Dario Lasagni.

What has it meant for a culture borne of the street to not only enter the museum, but to figure on the runway and as popular entertainment?

What it means is America has no choice but to recognize the people who created hip-hop. I always say that Black music is a reflection of and reaction to the environment in America, and hip-hop is a reflection of and reaction to that environment. The folks coming from these environments, telling these stories, having this language, and dressing the way they do represent us. America has no choice but to understand and recognize that this is American culture.

Usually America recognizes this when America realizes they can make lots of money. When white people see themselves in things that we create, then it becomes something that America embraces. This is not the first time this has happened. Look at rock and roll. I grew up at a time where kids in my own neighborhood would tell me that rock and roll was white boy music and I was like, “Don’t you understand that the pioneers of rock and roll were Black?” Look at what’s happening in Florida, and how people in government are trying to erase history.

History is the most important thing. If you don’t know your history, you don’t control your future. I think that’s what the show represents. You can see what the story is if you walk the entire show and you can see how hip-hop evolved over 50 years. You can’t hide it because photographs show you the truth.

“Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious” is on view at Fotografiska New York, 281 Park Ave S, New York, through May 21.