After Canadian photographer François Brunelle noticed that he bore an uncanny resemblance to actor Rowan Atkinson he got an idea.

In 1999, he started snapping photographs of people around the world alongside their doppelgangers—people who look strikingly similar but have no blood relation—for an ongoing project he titled “I’m not a look-alike!”, the New York Times reported this week.

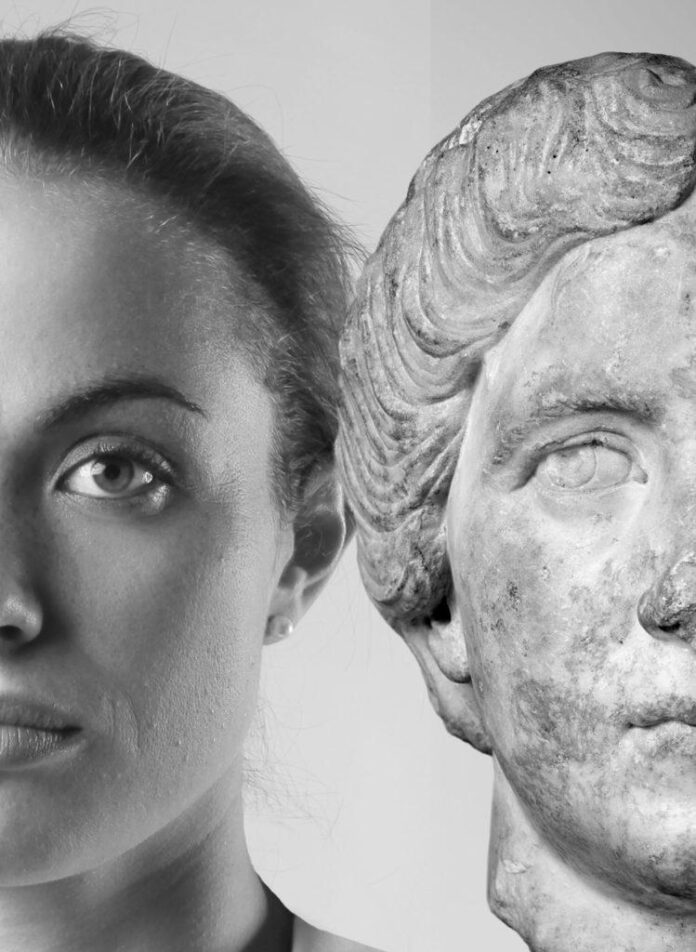

By 2015, Brunelle had “amassed a massive collection spanning over 250 lookalikes from over 30 cities around the world,” according to . The photos are black and white, an effort to “eliminate superfluous elements, like skin and hair color, and allow more focus on the essential similarities in facial structure between the two look-alikes,” Brunelle has said on his website.

He has been staging exhibitions and special projects of the work around the world, from Quebec to Bogotá—and it has been getting some unexpected attention.

Earlier this week, researchers from the Leukaemia Research Institute in Barcelona published a study in that was inspired by Brunelle’s photo project. Using facial recognition software, the researchers quantified each of 32 pairs’ physical similarities and found that 16 of the them were “true lookalikes” who had similarity scores similar to identical twins.

Artist Rob Pruitt’s celebrity lookalikes series at Art Basel Unlimited.

Participants also took DNA tests and answered a questionnaire about their lifestyles. Researchers found the “true lookalikes” shared genes—in fact, significantly more genes than the other half of subjects in the study shared with their counterparts. “These people really look alike because they share important parts of the genome, or the DNA sequence,” co-author Manel Esteller told the .

But while they shared genetic factors, “true lookalikes” still had different epigenomes, microbiomes, and fingerprints.

Traditional lore says spotting your doppelganger is bad luck—a sign your days are numbered. Esteller, on the other hand, attributes the phenomenon to chance. “Now there are so many people in the world that the system is repeating itself,” he told the .

Esteller said he hopes such studies will improve doctors’ ability to predict illnesses. He also wondered if a link between appearance and experiences meant faces could predict behaviors. However, peers like Daphne Martschenko at the Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics, who was not involved in Esteller’s study, quickly shot that down due to ethical implications.

“We’ve already seen plenty of examples of how existing facial algorithms have been used to reinforce existing racial bias in things like housing and job hiring and criminal profiling,” Martschenko told the The study “raises a lot of important ethical considerations.”

Charlie Chasen and Michael Malone, best friends who took part in Brunelle’s project, told the they see in both the photography project and Esteller’s research “another way to connect all of us in the human race.”