In 2019, British artist Bafic created an installation on the floor of a London gallery, featuring a giant selfie of his grinning face. Titled Walkover.me, the work asked visitors to step all over the portrait, during which an overhead camera would sneakily snap their photo. Not that these viewers weren’t warned about being surveilled: plastered around the edges of Bafic’s five-by-seven foot selfie were hundreds upon hundreds of small yellow stickers that cheekily announced, “WARNING! Smile, we’re on camera.”

The artwork itself is no longer physically installed, but that tiny sticker, created and produced by Bafic, has had a surprising and very long afterlife. Over the next few years, it would pop up across the world, all over social media, in the most unlikely of places.

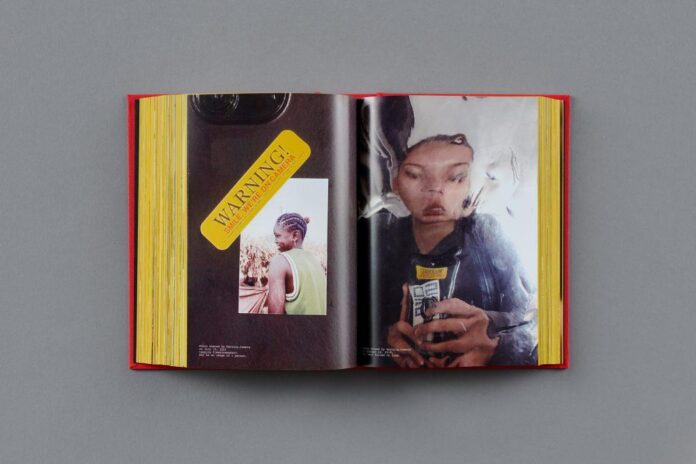

So virulent has been its spread that an Instagram account was set up to document its global crawl, and now, a hardcover book, titled Warning.Camera, has dropped to compile a whopping 2,061 images, each representing an instance where the sticker has appeared in the world between 2019 and 2022.

A page from . Photo: Theo Cristelis.

Someone’s parents had it on their doorbell in Australia, someone else handed some to security guards in Ghana, then someone showed up with one on a production set for U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders. Fittingly, most stickers are found stuck to the back of people’s smartphone cases. Bella Hadid had one, as did the late Virgil Abloh.

“A friend told me he was in L.A. and in this hotel room for a week, going in and out. And on his last day there, he went to leave and saw the sticker above the door of the room,” Bafic told Artnet News. “He messaged me, ‘Bro, what is going on?’ I was like, I have no idea.”

Bafic only has the roughest idea of how the sticker got out there. The artist had handed out surplus stickers to friends and acquaintances at the show’s opening, but because people kept asking after it, he kept making more and passing them out. He estimates he gave out around 10,000 stickers; an organic virality did the rest.

With the sticker’s expanding footprint, Bafic has come to view it as an accessible vehicle that has transported his work beyond the gallery. It represents, in effect, a real-life meme.

“I had made this installation and within it was another piece that wasn’t even presenting itself as a piece,” he said, likening it to how samples are often embedded in rap music. “There’s something about making something that was so small and ‘insignificant,’ but was heavy and light.”

The Warning sticker. Photo: Bafic.systems.

True, for such a slight piece of work, the sticker messages on several fronts, even as an unintended project. It points to a surveillance state where cameras are ever-present; it passes comment on an image-obsessed culture; it digs into our entanglement with social media. For Bafic, the sticker’s spread further surfaces the nature of virality itself.

“There are all these lofty terms, but I bring it down to how we distribute images across the internet, how we send images amongst each other,” he said. “I keep going back to our relationship with images versus our relationship with ourselves. What does it mean in the present day when images are so present in everything that we do? What are the politics of that?”

Bafic. Photo: Jim Joe.

This concern with image-making runs throughout Bafic’s own practice, which has used video and photography to probe what is being watched and who’s doing the watching. For instance, his 2018 installation, Processing Procession, invited audiences to London’s ICA to watch a film that was intercut with a live camera feed of the same audience watching the film.

In their immediacy and accessibility, these visual formats also befit an artist who, in his own admission, embarked on documentary photography earlier on only to find it “boring.”

A page from . Photo: Theo Cristelis.

A page from . Photo: Theo Cristelis.

“That’s such a big statement, but I felt like documentary photography, in terms of aesthetic, just stood still,” he said. “It didn’t advance with the times and it was just replicating things that had happened before. There weren’t new aesthetics or new approaches or new stories.”

“Meanwhile,” he added, “I’d look at my phone and my desktop, and I was obsessed with screenshots and ‘low’ quality images and stuff like that.”

Bafic’s project taps into exactly those veins, the sticker being an art piece of humble quality but with an outsized, non-static presence. Having been borne this far along a very 21st-century momentum, it continues to be a living, evolving work.

“It’s a breathing thing,” said Bafic about the project. “It doesn’t just sit in a white-walled space with no context. Its meaning changes depending on where the viewer is standing, and what vantage point they’re looking at. It’s come from the world.”