At this stage in the conversation, many of us understand that A.I. models were trained on data scraped from the internet, which means that they have been unwittingly codified with all sorts of age-old biases learned from humans, and tend to privilege the cis white male as society’s gold standard. So what better way is there to illustrate and subvert the flaws in the technology than through the art of drag, with its long history of bringing to light and lampooning outdated norms and rigid identity categories?

That is the idea behind S, a deep fake cabaret by the London-based new media artist Jake Elwes. Although the show exists in an interactive format online—inviting viewers to pick from a list of possible drag performers and songs—an in-person version inaugurated the digital gallery at the V&A’s brand new Photography Center, which opened to the public last week. The installation features a large projection of three performers dancing while, in the opposite corner, a row of LED screens show six singing heads that periodically shape-shift into each other with each song change.

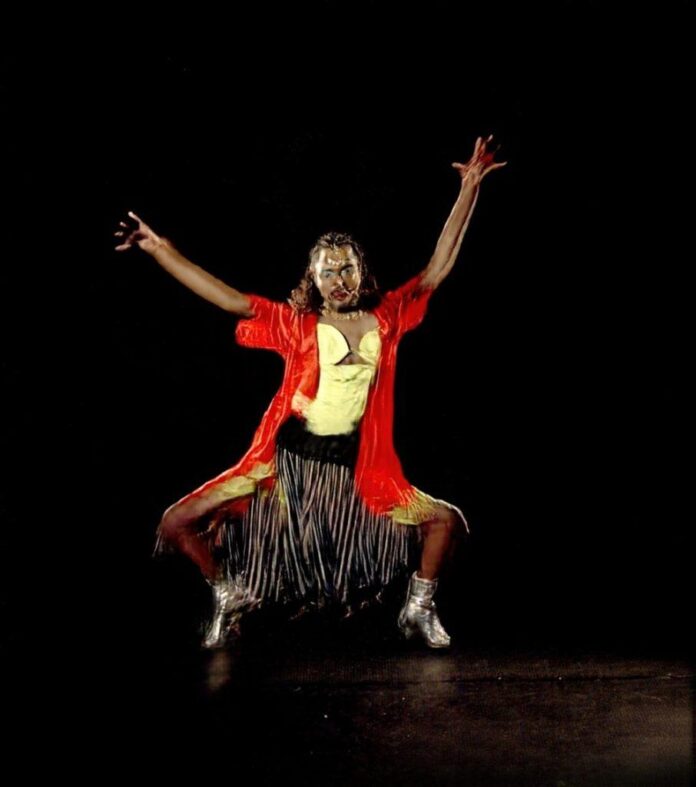

These moving images are deep fakes. Twenty one artists representing the many genders, sexualities and subcultures from the London drag scene were each filmed walking around a room so that a still from every angle could be used as a dataset. Elwes used a technique known as “skeleton tracing” to reduce the figures down to a series of moving points that the A.I. then learnt, over time, to convert back into a recognizable person.

For example, although only Ruby Wednesday was filmed dancing to by David Bowie, all 21 of the queens, kings, and quings are able to make the exact same moves on screen. But do these A.I. performers match up to the real thing?

Installation view of Jake Elwes and The Zizi Show (2020-2023) at the V&A Photography Centre in London. Photo: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

“It’s a bit tongue in cheek,” said Elwes. “Right now we are talking about whether A.I. is going to replace the human artist but this is a bit of a joke because A.I. is never going to replace a human drag queen or king.”

Certainly, it’s impossible not to notice how the performers, for all their colorfully eclectic accessories and make-up, persistently flicker and occasionally glitch on screen. “My favorite moments are when it fails,” said Elwes, recalling a moment when one performer, Cara Melle, dropped into the splits and the A.I. never worked out how to handle this statistical outlier.

Within the short history of A.I. art, Elwes is something of an early pioneer. “Everyone has been losing their shit over this new technology, but I’ve kind of been aware that it was coming,” they said, having first started working with A.I. in 2016 at the implausibly named School of Machines, Making and Make-Believe in Berlin. They immediately took to the art of programming, finding open source code to hack so that they could build a new tool and study the ways in which it fell apart.

This conceptual approach informed Elwes’s works for several years, as is evident at a retrospective that just opened at Gazelli Art House in London’s Mayfair (until July 8). (2017), for example, explores what happens when A.I. talks to itself while (2016) shows how these tools can be reverse engineered, in this case to generate rather than filter pornographic imagery.

Jake Elwes, A.I. Interprets A.I. Interpreting ‘Against Interpretation’ (Sontag 1966) (2023). Photo: Gazelli Art House.

Over the past year, Elwes hasn’t bothered much with the newest, viral A.I. generative tools like DALL-E and Midjourney, preferring instead to build their own datasets and models from scratch. An exception was made for (2023), which asks the A.I. to interpret a line of text from Sontag’s seminal essay into an image and then make a label to describe the image, bringing layers of hallucinogenic interpretation to esoteric topics like mimesis and form. “It’s a bit of nerdy art theory joke,” said Elwes.

In general, however, Elwes’s interests have shifted away from the philosophical implications of A.I. towards the political. “I now feel like those things were a real distraction,” they said. “Artists have a responsibility, actually, to be honest about what they using and deconstruct it. To show the conceit.”

In 2019, Elwes started , which took standardized facial recognition systems and fed them thousands of images of drag performers. “We queer that data so it shifts all of the weights in this neural network from a space of normativity into a space of queerness and otherness. Suddenly all of the faces start to break down and you see mascara dissolve into lipstick and blue eye shadow turn into a pink wig. It’s wonderful.”

For the project’s current iteration, , the issue of consent took center stage. Against the backdrop of ongoing controversy over Big Tech’s shameless mining of copyrighted content to feed their mammoth datasets, Elwes is developing a non-exploitative model for making art with A.I.

Jake Elwes, The Zizi Show (2020-2023) at the V&A Photography Centre in London. Photo: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

After all, in the wrong hands “this technology, specifically deep fakes, can be used for really dark purposes.” Elwes paid every performer for their participation, acquired their consent to be in the dataset, and ensured they understood exactly how their body will be manipulated, and that they have the freedom to withdraw from the project at any point. “The only people who have the right to re-animate the bodies of our queer performers are people form within that community,” Elwes said.

The result is a celebratory, expressive performance with a charming humanity that has been sorely missing from most pieces of A.I. art. The audience’s enjoyment of the work also feels refreshingly uncomplicated.

“I do think the project has additional poignance right now,” said Elwes. “It’s amazing to have this in the V&A because Congress is discussing A.I. safety, I have friends who are drag queens who are having right-wing protestors outside their shows right now and there’s obviously a lot of anti-trans sentiment in parliament. It’s a tough time for the queer community.”

“What if AI was only built by queers?” Elwes then wondered aloud, with growing excitement. “Imagine that! It might serve the world a lot better if it was people who are thinking from an outsider’s point of view.”

They pointed out that, after all, the tech-optimistic take on A.I. insists that these tools are going to help build a better society. “How can we get to that? This is my deep fake drag utopia.”