Earlier this year a leading US collector wrote to Art Basel’s management saying he refused to set foot in Florida for the Miami fair this week after the so-called “don’t say gay” bill was passed by the state in March. The legislation restricts primary schools from teaching pupils about sexual orientation and gender issues.

The man behind the bill is Florida’s governor and Fox News favourite Ron DeSantis, who earlier this month coasted to a second term and is expected to run for president against Donald Trump in 2024. DeSantis is waging a culture war on other fronts, too: he has banned abortion after 15 weeks in the state and recently introduced the Stop Woke Act, which limits teaching on critical race theory, including the concept of white privilege. A small reprieve came in August, when a judge issued a temporary injunction on the latter bill, describing it as “positively dystopian”.

Dystopia has become an all-too-familiar scene in US politics, but Florida’s shift from swing state to solid GOP is of particular concern to some of the leading cultural figures in Miami. As the Argentinian-born mega-collector Jorge Pérez puts it: “I hate to see where the country is now. People’s opinions are so extreme, there’s no discussion and no in between.” He thinks free speech is the cornerstone of US society. “Everybody should have the right to artistically express whatever they want,” Pérez adds.

Robin Kid, aka The Kid, God Bless Our Broken Home (2022) Eric Thayer

Born to Cuban exiles, Pérez is among a powerful cohort of collectors in Miami, but political allegiances in the city are mixed. Norman Braman, Rosa and Carlos de la Cruz and Ken Griffin have all given generously to the Republican party, while Mera Rubell and Martin Margulies have written cheques for the Democrats.

Pérez, a longtime supporter of Hillary Clinton who also backed the Republican Jeb Bush, describes himself as a “liberal Democrat”. He adds: “I’m not a DeSantis person, and I’m not a Trump person. On the other hand, I think the Democratic Party has gone a bit too far to the left.” Of his one-time friendship with Donald Trump, Pérez says the rift developed when he declined to back Trump’s presidential bid, citing differences over “almost every policy”, including immigration and the environment.

So how is Florida’s lurch to the right impacting Miami and its cultural scene?

Despite the chilling effect of the state’s increasingly right-wing politics, Pérez notes how Florida’s low-tax, pro-business approach has contributed to “another revival” of Miami’s cultural scene, which has mushroomed with the influx of wealthy individuals and corporations since the pandemic. “The growth has been immense, and it’s brought art with it,” Pérez says. “Miami is no longer just a sun and fun city, it’s a serious place for business and art—and that’s now happening year-round.”

Pérez has been instrumental in Miami’s cultural levelling up. Since 2011, the collector, who made his fortune developing luxury condos, has contributed $55m to the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM, formerly the Miami Art Museum), including significant collections of Latin American and Cuban art—a move which secured his name above the door. He has also recently donated to the Tampa Art Museum and the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town.

His collecting continues apace—since his last donation to PAMM in 2017, Pérez has purchased more than 5,000 works, around 700 of them by Cuban artists, many acquired after the protests of 11 July 2021.“We started buying like crazy because [artists in Cuba] needed money,” Pérez says. Works by Tania Bruguera, Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons, Carlos Garaicoa and Rubén Torres Llorca are among those currently on show in the exhibition, You Know Who You Are, at his private gallery, El Espacio 23.

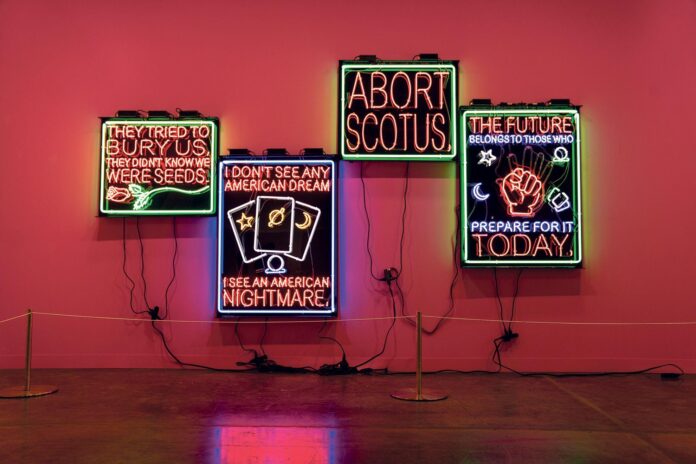

Challenging issues are being confronted in exhibitions elsewhere in the state. At the Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU, the photographer Bonnie Lautenberg tackles women’s rights, particularly the US Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v Wade. Most abortions are now banned in at least 13 US states.

“It’s outrageous that women don’t have the right to choose what they want to do with their bodies,” Lautenberg says. “This is a threat to our democracy. The same people who stole our right to choose will eventually try to steal our other hard-won rights too.”

As part of her retrospective, Lautenberg is also showing Guns Kill (2022), a piece that superimposes the Statue of Liberty over images of AR-15-style rifles. The work was created to benefit Giffords, an organisation dedicated to saving lives from gun violence led by former Democrat Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, who was seriously wounded in a mass shooting in 2011.

The photographer points out how the same senators who are pro-life are often also anti-gun control. “It’s so hypocritical,” she adds.

Lautenberg, who splits her time between New York and Palm Beach, is the widow of the long-standing Democratic senator Frank Lautenberg. She notes how Latino voters in Florida have swung to the right. An estimated 72% of registered Republicans in Miami-Dade are Hispanic, many of them Cuban-American. “When I used to go to fundraising events in Miami with my late husband, most Latinos were Democrats. The Cubans supported us, but now lots of them have gone to the right,” she says.

Indigenous artist Hock E Aye VI Heap of Birds’s (Cheyenne and Araphaho) Florida Today Your Host is Timucua (2022) is one of a series highlighting the issue of Native American land rights Eric Thayer

Lautenberg suggests that traditional “Latino” issues such as immigration, combating racism and identity politics now often take a back seat to concerns over the economy, religion and foreign policy.

For many in the Miami art world, encouraging diversity remains a priority. The main impetus behind Gabriel Kilongo setting up his gallery, Jupiter, in March was to give a platform to artists from different socio-cultural backgrounds. The dealer, who fled his native Democratic Republic of the Congo after the wars of the 1990s and 2000s, initially moved from New York to Miami at the outbreak of the pandemic to set up a pop-up for the gallery Mitchell-Innes & Nash. It was so successful that Kilongo branched out on his own and next month opens a new space that more than doubles his current gallery’s size.

This week, Kilongo is exhibiting at Untitled Art fair, where is he is showing paintings by the self-taught Seattle artist Marcus Leslie Singleton (prices range from $3,000 to $20,000).

He notes the number of “polarising figures” in Miami, but also points out how his colleagues in the gallery world “tend to represent political values that completely contradict what the average Miami person thinks”.

Miami’s institutions, too, champion a diverse mix of artists, even if their financial backers hold conservative views. Norman Braman, for example, is the main benefactor of the ICA Miami, which is known for its progressive programming. “It’s one of many museums in Miami that shows artists who challenge the beliefs that DeSantis and Trump have,” Kilongo says.

The dealer thinks that the perception of Florida as an ultra-conservative state is being further challenged by a group of forward-thinking collectors who are launching spaces, including Beth Rudin DeWoody, who opened The Bunker in Palm Beach in 2017, and Ariel and Daphna Bentata, who are reportedly building a space which will champion queer and Black artists.

“Culturally speaking, in the next decade Miami will start to challenge cities like New York and Los Angeles,” Kilongo believes.

Nonetheless, DeSantis still represents a threat to many in the Sunshine State; as the governor put it himself: “Florida is where woke goes to die.”

His stance is not lost on some of the artists exhibiting at Art Basel in Miami Beach this week. The Dallas-based artist Leslie Martinez is showing a suite of new abstract paintings with the Texan gallery And Now.

Created “specifically for this moment”, as Martinez puts it, their work emerges from the artist’s trans non-binary identity and ancestral history in the Rio Grande Valley of the Texas-Mexico border.

So what exactly does “this moment” signify for Martinez, who is exhibiting for the first time in Miami? “I’m struggling with a deep sense of sadness and anger because I’m coming from one really anti-queer state to another with my work,” they say. “But then I think ‘fuck yeah, I’m bringing the most ‘say gay’ paintings I can to Florida’. Bringing my work to this state speaks directly to that bill—no matter how much anyone tries, there is no way to erase us.”