For the first time in its almost 130-year history, female artists significantly outweigh men at this year’s Venice Biennale (until 27 November). Among them are Sonia Boyce, who won the Golden Lion for her British pavilion presentation; Zineb Sedira, who has garnered rave reviews for transforming the French pavilion into a cinematographic installation; and the social activist Acaye Kerunen, who is representing Uganda with Collin Sekajugo.

The impact on the market has been almost immediate. In the run up to the biennial and since, these women have all been signed to major galleries—some for the first time in their long and remarkable careers.

Simon Lee is giving Boyce her first solo show with the gallery during Frieze this week; the London dealer announced his representation of the artist in May 2021, telling The Art Newspaper at the time: “We look forward to amplifying Sonia’s vital and urgent voice, to build a legacy for her practice at an international level.” (Boyce continues to be represented by Apalazzo Gallery in Italy.)

In 1987, when she was just 25, Boyce became the first Black female artist to enter the Tate’s collection when the museum bought her drawing, Missionary Position II (1985), for an undisclosed sum. Around that time, she moved from drawing to a more performative social practice, which has arguably been more difficult to collect, particularly for private buyers. The gallery declined to comment on prices, but a spokesperson says Boyce’s solo show “has been extremely well received, both from a critical and commercial perspective”.

Sonia Boyce’s show, Just for the Record, at Simon Lee Gallery; the exhibition is the artist’s first with the gallery, which she joined last year Photo: Ben Westoby; Courtesy of the artist and Simon Lee Gallery

Like Boyce, Sedira’s practice leans towards the archival and communal. Last month, the French-Algerian artist joined Goodman Gallery, which has spaces in South Africa and London. (She is also represented by Kamel Mennour in Paris.) Surprisingly for someone who has been based in the UK capital for more than 30 years, Sedira says she has never been approached by a London gallery—perhaps, she suggests, “because my work is focused on French imperialism rather than British”. She adds: “I’m in this funny space; I’m Arab and African. I’m too white to be black and too dark to be white.”

Agency input

Goodman Gallery, meanwhile, expressed interest after seeing her pavilion in Venice. There are now plans for Sedira to show at the gallery’s Cape Town space in November, while an “institutional show in London is in the pipeline”. Her prices range from $20,000 to $100,000.

Pace Gallery, which now represents Kerunen together with Blum & Poe and Galerie Kandlhofer, signed the artist last month after seeing her work in Venice. The deal has been overseen by the Belgian agency, Stjarna.art, which has managed Kerunen since 2021. “They ensure that all my galleries are telling a coherent story of myself, my work and of Africa,” the artist says. “There is a tendency for galleries to tell a story that serves their best interests rather than their artists’.”

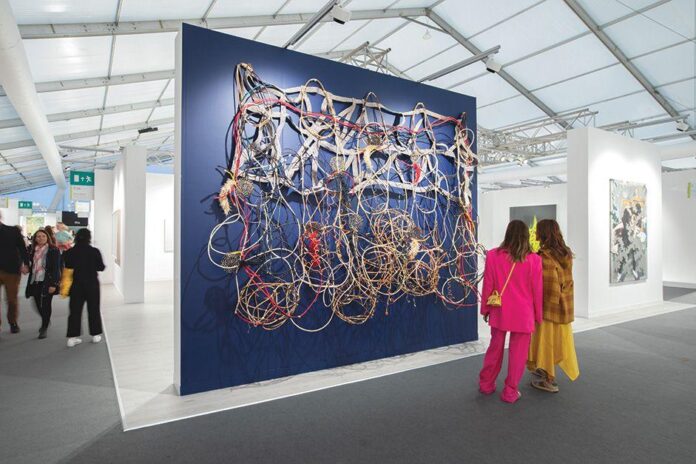

Representation and context is key, Kerunen says: “When you go through Frieze London, how many works shown at these major galleries do you see by an African using Indigenous practices?” Equally crucial are the terms of her signing, which include clear rules she has established to “protect her mental health”, such as a limit to her rate of production. “It’s quite unprecedented in these galleries. It’s a new language we’re creating,” she says. Pace is showing a large wall sculpture by Kerunen created from banana fibre, raffia, reeds and palm leaves. Priced at $90,000, it is currently on reserve to a museum.

Older female artists who have been without gallery representation are being found through other platforms, too—most notably, via Instagram. Anne Rothenstein, who recently joined Stephen Friedman Gallery, was discovered on Instagram by the art historian and broadcaster Katy Hessel, who introduced her to the gallery. Rothenstein’s solo show at the gallery is sold out. (Prices range from £40,000-£75,000.)

Rothenstein, now in her 70s, has been a painter all her life but only began to embrace her career five years ago, according to gallery director Jon Horrocks. “Before that, she gave her life to being a mother and a wife,” he says.

Installation views of Caroline Coon: Love of Place at Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, 2022 Courtesy of Stephen Friedman Gallery, London; Photo: Mark Blower

Another recent recruit is showing in Stephen Friedman’s other London space: Caroline Coon, an activist, journalist and one-time manager of the rock band The Clash, who is also in her 70s. For a time, Coon supported her artistic practice as a sex worker. Horrocks says: “She wanted to work with galleries, but they wouldn’t touch her with a bargepole. When she studied at Central St Martins [in the mid-1960s], figuration wasn’t popular, plus she’s a staunch feminist, which perhaps wasn’t as palatable.”

As a result, the majority of Coon’s work has never been seen before—all but one of the paintings on show in London have been hidden away in her studio, some of them since the late 1990s. Priced at £75,000 each, the canvases, of everyday life in west London, have all found homes—mainly with US collectors.

While such additions to dealers’ rosters go some way to redressing longstanding imbalances in the market, which are being challenged by movements such as #MeToo or #BlackLivesMatter, there are still huge discrepancies across the majority of galleries—both in terms of representation and prices.

Of the 47 artists listed on Simon Lee’s website, 16 are women. Of Goodman Gallery’s 48 artists, 16 are women. Pace represents 123 artists, 33 of them women; while, at Stephen Friedman, 13 out of 35 artists are women.

Consistently devalued

The price gap is more difficult to gauge in the primary market—though, anecdotally, women’s art is consistently devalued compared with men’s. A recent survey of secondary market auction prices found that for every £1 a male artist earns for his work, a woman earns just 10p.

Of the pricing at Stephen Friedman Gallery, Horrocks says gender is never a consideration; rather, they look at “quality and rarity of value”. When it comes to Rothenstein and Coon, he adds: “We are trying to give them the recognition and respect they deserve.”

Pricing Kerunen’s work, meanwhile, is veering into newer territory. Marc Glimcher, Pace’s president and chief executive, says the artist “takes an active role in everything”, including pricing. “It’s all about sustainability and the amount of pressure you put on production,” he says, adding: “Artist representation is more complicated than it’s ever been. We’ve seen a lot of artist agencies pop up in the last year, functioning as managers and agents.”

Not everyone is convinced by the emerging model, however. Ellie Pennick, the founder of London’s Guts Gallery, which champions under-represented voices, says: “You can reform the industry from inside, but to what extent I’m not sure.”

Meanwhile, KJ Freeman, the owner of HOUSING Gallery in New York, describes Pace’s representation of Kerunen as an “example of neoliberalism”. She points out the inherent contradictions of a blue-chip gallery working with politically engaged artists. “I think it may be impossible for mega-galleries to embody a pure activist spirit—it would be a contradiction of their practice, and the very clients they have,” she says.

Nonetheless, she concedes, “There’s nothing wrong with what Pace is doing because they are a multi-million dollar gallery empowering Acaye. That alone should be where their activism begins and ends. To expect more from them would be to transform the very nature of a blue-chip gallery.”