The late Canadian artist Rodney Graham is getting a posthumous spotlight at Hauser and Wirth’s Somerset outpost.

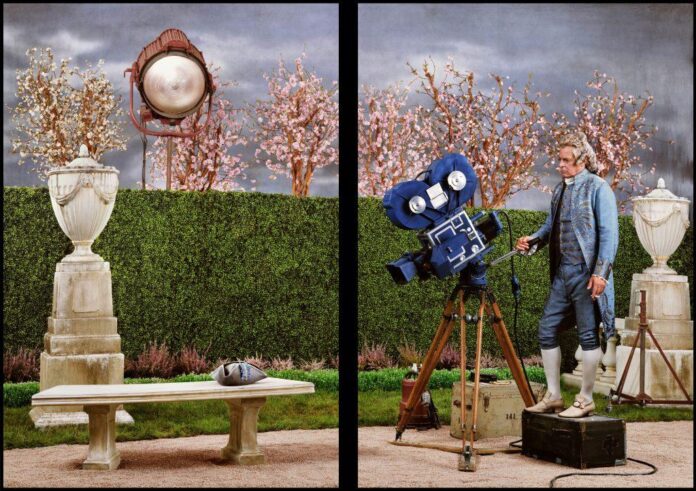

After a breakout turn representing Canada at the 1997 Venice Biennale, the conceptual artist, who passed away last fall from cancer at 73, became known for his dryly humorous films and photographs in which he often cast himself in various elaborate guises and scenarios. The show, on view through May 8, includes a series of large-scale lightbox photographs that thrust the viewer into a number of Graham’s richly imagined worlds. Filled with textured detail they bring a vibrancy to otherwise banal scenes; an overworked chef taking a cigarette break, an unkempt hermit jubilating in front of a ramshackle cottage.

The exhibition also nods to other dimensions of Graham’s practice, which stretched to encompass adept painting, sculpture, photography, and musical work. Called “Getting It Together in the Countryside,” the show borrows its title from Graham’s 2000 LP of the same name, a jam session of improvised guitar recordings—fitting for the gallery’s rural British location, which Graham visited to perform at its opening in 2014.

Rodney Graham, Betula Pendula Fastigiata (Sous-Chef on Smoke Break) (2011). ©Rodney Graham. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Throughout his career, Graham seamlessly inhabited his various characters. “It may be a burden to reinvent oneself every time,” Graham said, “but it makes things more interesting.”

The centerpiece of the exhibition is Graham’s The Four Seasons, a late body of work executed between 2011 and 2013. The series was inspired after Graham’s fellow artist and friend David Batchelor remarked that two images of characters—a drywaller and a chef—enjoying smoke breaks, reminded him of summer and winter. This spurred Graham to make two more companion pieces, another smoke break, this time of a Hollywood actor/director on a technicolor film set in the 1950s to represent spring, and a fourth, more meditative take on a kayaker on the Seymour river for fall, which he joked was his chance to take an “oxygen break.”

The exhibition also dips into other aspects of his practice, opening on one of his sculptures, an innocuous-looking door propped against a wall. It could be any old screen door—they are pretty ubiquitous fixtures—but this particular one happens to be an exact replica of Elvis Presley’s door at Graceland. Graham was tickled when the object was offered up for auction alongside other Elvis memorabilia in 1999 and ran with it, deciding to cast the replica in solid silver.

One example from his “inverted trees” series following the artist’s early experiments with the camera lucida, a large-scale pinhole camera that dates back to ancient times, is also on view.

“Getting It Together in the Country” is far from a complete overview of Graham’s polymathic practice, but it is one of the last exhibitions of his own work that he had a hand in organizing, and aptly showcases him as a unique artist, masterfully aloof, and still winking from beyond the veil.

Rodney Graham, Main Street Tree (2006). ©Rodney Graham. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Tom Van Eynde.

Installation view, “Rodney Graham. Getting it Together in the Country,” Hauser & Wirth Somerset, 2023. ©Rodney Graham. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Ken Adlard.

Installation view, “Rodney Graham. Getting it Together in the Country,” Hauser & Wirth Somerset, 2023. ©Rodney Graham. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Ken Adlard.

Rodney Graham, Paddler, Mouth of the Seymour (2012-2013). ©Rodney Graham. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Installation view, “Rodney Graham. Getting it Together in the Country,” Hauser & Wirth Somerset, 2023. ©Rodney Graham. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Ken Adlard.

Installation view, “Rodney Graham. Getting it Together in the Country,” Hauser & Wirth Somerset, 2023. ©Rodney Graham. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Ken Adlard.