The Seattle chapter of the National Audubon Society is distancing itself from the organization’s problematic namesake, John James Audubon, by officially dropping his name.

The resolution was unanimously passed by the chapter’s board of directors on July 14 and was described by the board’s president, Andrew Schepers, as “another down payment” on a strategic plan formed in 2020 “toward building a more equitable and just organization.”

“It will not be easy,” he said. “But neither is accepting the status quo of continuing to glorify and mythologize a white supremacist.”

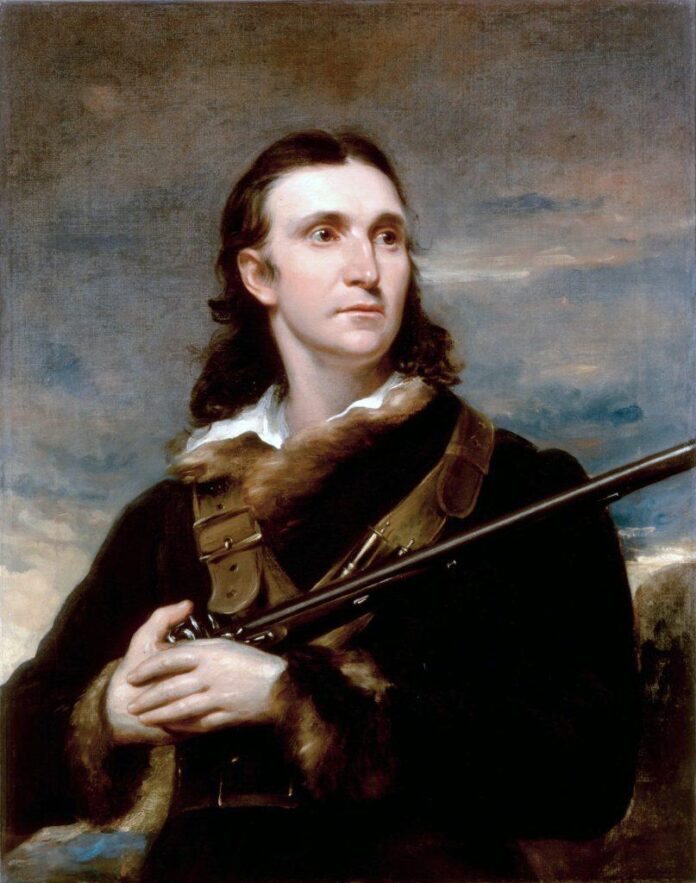

The national umbrella organization’s biography of its namesake, titled “John James Audubon: A Complicated History,” notes that despite his many talents, Audubon was a slaveowner and avowed racist who was accused of academic fraud, “plagiarism, and invention” to gain promotion from English nobility.

Audubon, along with another ornithologist, John Kirk Townsend, dug up and stole the human remains of Mexican and Native Americans as part of a bid to prove the inferiority of non-white peoples.

“The shameful legacy of the real John James Audubon, not the mythologized version, is antithetical to the mission of this organization and its values,” Claire Catania, the executive director of the Seattle chapter, said in a statement. “Knowing what we now know and hearing from community members how the Audubon name is harmful to our cause, there is no other choice but to change.”

The National Audubon Society, which was formed decades after Audubon died, got its name because cofounder George Bird Grinnell was tutored by John James’s widow, Lucy Audubon, in the late 1800s.

The Washington, D.C.-based Audubon Naturalist Society, which is not affiliated with the National Audubon Society, has also stated its intentions to drop the Audubon name and announce a new one in October.

The moves are part of a wave of similar changes. In 2020, the Sierra Club issued a statement denouncing the racist views of its founder, naturalist John Muir, and in March 2022, the University of California, Davis approved a recommendation to rename its John Muir Institute of the Environment to the Institute of the Environment. In June, the Ashland, Oregon-based John Muir Outdoor School was renamed the TRAILS Outdoor School.

Audubon’s origins are murky. He was born in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) to a plantation owner and a mother who was either a French chambermaid named Jeanne Rabine or a Creole housekeeper named Catherine Bouffard.

Kerry James Marshall’s 2020 series reimagining Audubon’s 435 watercolors is based in part on that question, and the fact that Audubon’s work was included in the 1976 exhibition “Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750–1950,” organized by David C. Driskell at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

“I didn’t know what to make of it, honestly,” Marshall said in an interview. “If somebody did the research and put it in a book, then maybe it must be true. And I never forgot that assertion was made.”

Audubon was sent to France at the onset of the Haitian Revolution, whereupon he began studying birds, drawing, and nature. He embarked on a mission to study and illustrate the birds of America in the early 1820s and found success with his dramatic renderings of the natural world in England, where was first printed in Edinburgh and then London.

While Audubon achieved modest financial success in his lifetime, in recent years, his legacy has been worth millions.

In 2018, the four-volume, double-elephant folio belonging originally to William Henry Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, the 4th Duke of Portland, sold for $9.65 million at Christie’s. Another, single hand-colored plate of the Carolina Parrot fetched $150,000 at Sotheby’s the next year.