Conservation and cultural projects in Pakistan’s Walled City of Lahore are moving at full speed despite the country’s rocky economy and uncertain political and security situation. On 15 February, in the midst of the Pakistani government’s negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bailout to rescue it from defaulting, and just two weeks after a brutal terrorist attack in Peshawar, the US ambassador to Pakistan, Donald Blome, visited the walled city and inaugurated a conservation project that will be funded with a grant of almost $1m from the US.

Located in the heart of Lahore, the second largest city in Pakistan and the capital of Punjab province, the walled city is a 2.6 sq. km area with 12 gates that lead to its famous historic houses, gurdwaras (Sikh places of worship), temples, bustling bazaars and narrow labyrinthine streets. Also known as the old city, it comprises around 100 historic monuments including 17th-century sites such as Shahi Hammam, built in the pattern of Turkish and Persian bathing establishments; Badshahi Mosque, once the largest mosque in the world; the Wazir Khan Mosque; and Lahore Fort, a Unesco World Heritage Site with 21 monuments.

Funded by the US Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation, the aforementioned project is a partnership between the Walled city of Lahore’s Authority (WCLA), the local administrative government body responsible for the historic site, and Aga Khan Cultural Service-Pakistan, a local entity of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. The initiative aims to restore seven sites at the Lahore Fort, including parts of the famous Picture Wall, Loh Temple, Sikh temple, Zanana Mosque, Sehdara pavilion, Athdara pavilion and Sheesh Mahal. The scheme is one of several planned heritage projects for the area as tourism in the city increases.

“Lahore—the old city—is pretty booming and doing well. This [past period], I think we have had the best of tourism. Lahore Fort in particular gets about five million people [visiting] per year,” Kamran Lashari, the WCLA director general, tells The Art Newspaper.

Documentation and restoration of the Lahore Fort’s Picture Wall began eight years ago and should be finished by the end of 2024 Aga Khan Trust for Culture

Pakistan has been in a state of political turmoil ever since its prime minister, Imran Khan, lost a no-confidence vote in April 2022. The former cricket star has been holding popular rallies across the country calling for early elections and objecting to a ruling that bans him from taking office for the next five years. The country has been grappling with economic hardships that saw inflation rise to 27% in January, a 48-year high, and its foreign currency reserves are barely enough to cover a month’s imports.

Spending priorities

However, these challenges have not deterred the WCLA and its partners from pursuing the preservation of the old city and its treasures. “Life is so complex and cannot be viewed just from one angle,” says Lashari. “We should be mindful and not overspend when money is not easily available, but conservation is part of life, otherwise underdeveloped countries would never be able to spend on arts, culture and conservation because the money is never enough.”

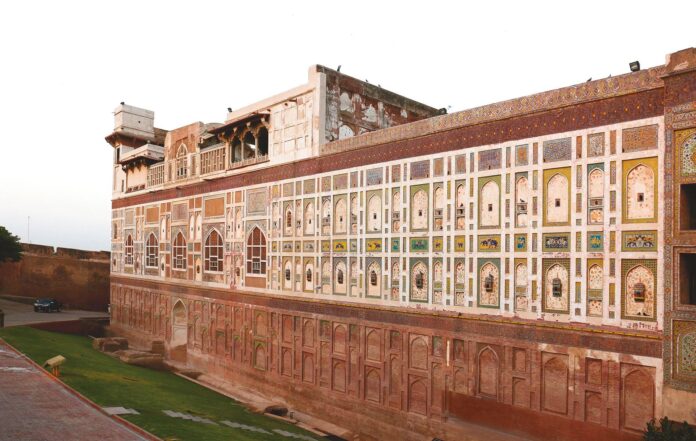

Although Lahore Fort’s foundations are more than a thousand years old, it was mostly built between 1556 and 1707 by Mughal emperors, and modified during the Sikh and British periods. Its listing as a World Heritage Site is largely due to its exquisite Picture Wall, one of the largest murals in the world at around 460 metres long and 16 metres high, with a series of brick-framed ceramic mosaic and fresco-painted panels that depict numerous celebrated mythological and royal scenes.

The complex work to document and preserve the Picture Wall, which began in 2015, is about 80% complete and expected to be concluded by the end of 2024. The Aga Khan Cultural Service-Pakistan and Aga Khan Trust for Culture have partnered with WCLA since its inception; their collaboration has not only contributed to preservation of historic monuments but also improved living standards for more than 200,000 low-income residents through the rehabilitation of properties and by creating safer living environments.

“Conservation is not the end, it is the starting point. Once the conservation is done, we should take our project socially and culturally and make it touristically active. So connecting buildings with people and connecting our open spaces with people has been the hallmark,” Lashari says.

He adds that more than 97% of the residents have lived in their properties for generations and form the essence of the old city, which benefits tourists. “They are part of the cultural heritage and the cultural showcase. If they are not there, I think the spirit of the place will be lost,” Lashari says.

Other ongoing and upcoming projects in the walled city include the $1m conservation of Wazir Khan Mosque and its surroundings, which is expected to be completed by 2024. The restoration and rehabilitation of two of the city’s 12 gates—Masti and Bhati—and the adjacent area are on schedule for this year. A five-year French-backed project to develop tourism, including forging a new visitor’s centre in the fort, is underway and planned to start on the ground in 2023.

WCLA has also been asked to lend its technical expertise to projects beyond the city. It is currently involved in the conservation of 11 churches, 12 shrines and a temple in the province of Punjab and the Red Fort, a 17th-century fort in Azad Kashmir.