Embroidery artist Cayce Zavaglia creates mesmerizing portraits of everyday people using cotton thread and wool. In this thoughtful video profile, Jesse Brass takes a closer look at Zavaglia’s process and speaks with the artist about her work. In their conversation, Zavaglia emphasizes the importance of seeing the beauty in ordinary life, and explains the symbolic significance of each portrait’s verso.

Cayce Zavaglia lives in St. Louis, Missouri, bravely owns up to having used puff paint—that favorite of crafters—in her early work, and is an unabashed fan of Martha Stewart. But if you think her embroidered portraits are some kind of homey Midwestern project destined for a local craft fair, guess again. This isn’t your grandma’s needlework.

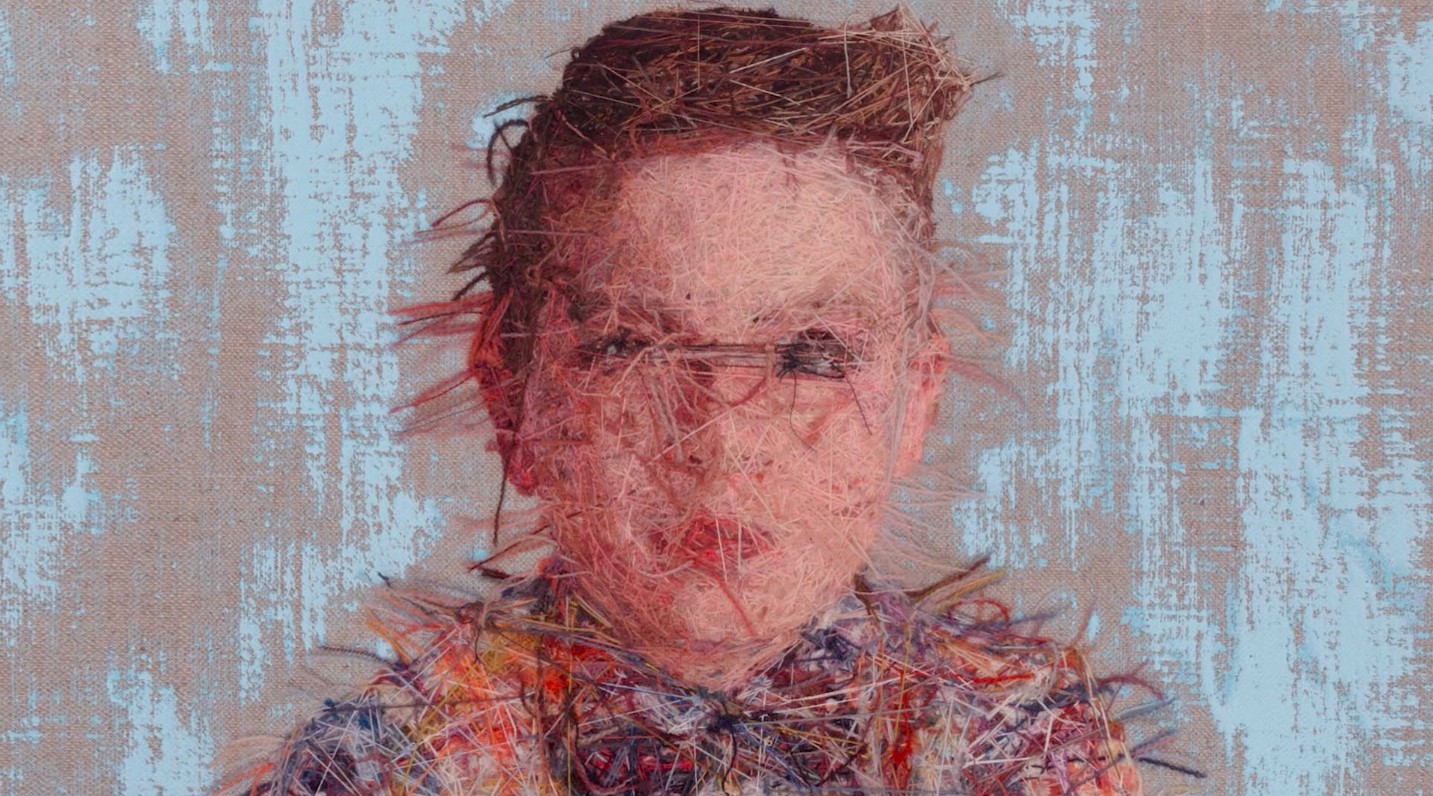

On the contrary, Zavaglia employs what she calls “renegade embroidery.” Yes, she uses a needle and thread, but she doesn’t follow any standard sewing rules, instead layering stitches every which way. She is far from alone among contemporary artists mining traditional women’s needlework—Ghada Amer and Elaine Reichek are well-regarded practitioners—but she is carving her own niche with uncannily photo-realist “paintings,” as she considers them.

Born in Indiana and raised primarily in Australia until she was 13, Zavaglia was an arts-and-crafts kind of kid. “I always loved to make craftsy things—and I’m not ashamed of that,” she says, recalling a particular youthful attachment to her glue gun. While an undergrad at tiny Wheaton College in Illinois, her professors suggested she could become a true artist and not just a Sunday painter. “It was like the curtains had opened,” she says. “It had never dawned on me.”

Born in Indiana and raised primarily in Australia until she was 13, Zavaglia was an arts-and-crafts kind of kid. “I always loved to make craftsy things—and I’m not ashamed of that,” she says, recalling a particular youthful attachment to her glue gun. While an undergrad at tiny Wheaton College in Illinois, her professors suggested she could become a true artist and not just a Sunday painter. “It was like the curtains had opened,” she says. “It had never dawned on me.”

Back then, her canvases were thick with “gobby” paint; in grad school, at Washington University in St. Louis, she applied the paint in thin layers. But all along, her subject matter has remained constant. “It’s always been about people I know—friends and family,” she says. “And it’s always been about the process, how the piece is constructed.”

When she became pregnant with her first child, she started casting about for an alternative to using paint and turpentine. Her mind kept returning to thread—her mother’s and grandmother’s handiwork; the knitting that Australian girls did on the train to school; a small, rudimentary embroidery she’d made as a child. Her husband thought she was crazy, but she was soon hooked on needlework.

Zavaglia toiled largely in obscurity until 2008, when her dealer, the New York gallery Lyons Wier, took a handful of her embroidered portraits to the PULSE art fair. All sold in the first two hours.

Her work is now among the most popular at the West Collection, in suburban Philadelphia, which is devoted to emerging artists. “Cayce’s technique is incredible,” says West’s director, Lee Stoetzel. “Like a Vermeer, it’s hard to believe a person can make such a thing.”

Zavaglia begins each piece by taking photographs of her subject against a plain gray background. After selecting an image, she transfers it to fabric, draws over it in sharp detail—”every line, hair, wrinkle,” she says—then starts to sew. The hair comes first, followed by the forehead, as she works her way down the face.

Describing the technique as “pointillist,” Zavaglia says she layers stitch atop stitch to achieve the desired color and subtle tone. A large work consists of roughly 80 to 100 colors of crewel wool and takes six to seven months to complete; a smaller one, made with finer, shinier thread, about six to eight weeks. Zavaglia has yet to count her stitches, but the tally is clearly in the thousands.

Embroidery has proved conducive to raising a family (Zavaglia’s brood now numbers four). “I can jump in and out of it,” she says, whenever she has a break. “Sometimes it’s an hour and stop, an hour and stop, working around carpool and nap schedules.” In fact, in the Zavaglia household, art has become a family affair. Her children sometimes join her in sewing, which she thinks is especially cool for her three sons, even if they do favor Star Wars motifs. Her husband, who is in the construction business, builds her frames and stretchers.

Though Zavaglia is clearly respectful of craft, she does believe there is a dividing line between it and art—“but I don’t know if I can articulate what it is,” she says. In her case, perhaps it’s the “wow” factor a viewer feels on closer inspection of the portrait on the wall, realizing it was painstakingly constructed from thread, not paint. “People want to touch it,” Zavaglia says. “I tell them, ‘If my dealer weren’t here, I would let you.'”

She has a show of new works coming up in May 2018 at Lyons Wier Gallery in New York. Brass shares many more artist profiles on Vimeo.