Many of the work of Alabama artist Bill Traylor, crisp silhouettes with vibrant, significant color blocks, painted on scraps of paper or someone else’s stationery – and the like. This wasn’t Traylor’s way of making a postmodern statement; he was just using the art supplies he had.

Bill Traylor was born in 1853. The artist was born into slavery. Works by Bill Traylor make an enigmatic and vital part of the American artistic canon.

This documentary, directed by Jeffrey Wolff, is a simple, heartfelt, and nutritious story about the artist. Wolf makes excellent use of photo and film archives, highlighting the territory that nourished Trailor’s vision: dirt roads, railways, deep forests.

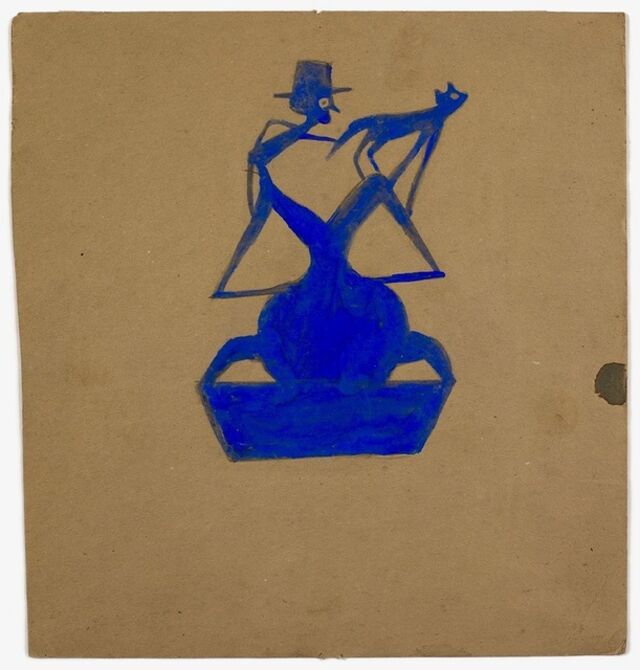

These passages, as critic and musician Greg Tate, notes in the film, lay the foundation for Trailor’s “mystical realm”: deliberately two-dimensional shapes and limited but bold colors have the mesmerizing power of waking dreams. In this area, blue is especially important. Tate speaks eloquently about embracing the blues to keep it out.

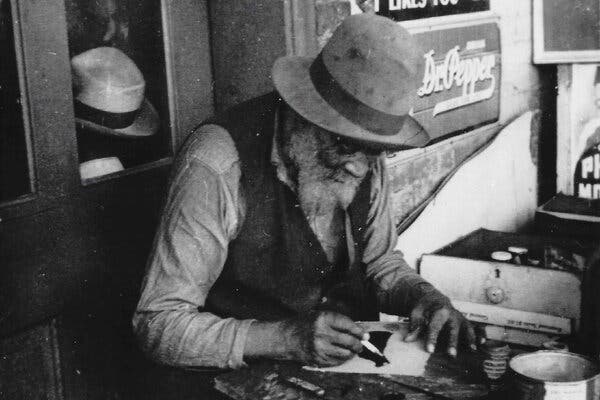

Memories of Monroe Street in Montgomery in the 1930s and 1940s – a city that never sleeps from that era, according to one of the interlocutors – are vivid. Bill Traylor opened a shop there, near the billiard room, painted with blunt tools and available paper, and slept in the coffin pantry at a nearby funeral home.

As a result, his health problems led to the amputation of one of his legs. In his drawings, he often looked back – to moments of respite from the traumatic world in which he grew up, for example, after having lunch at a local bathhouse.

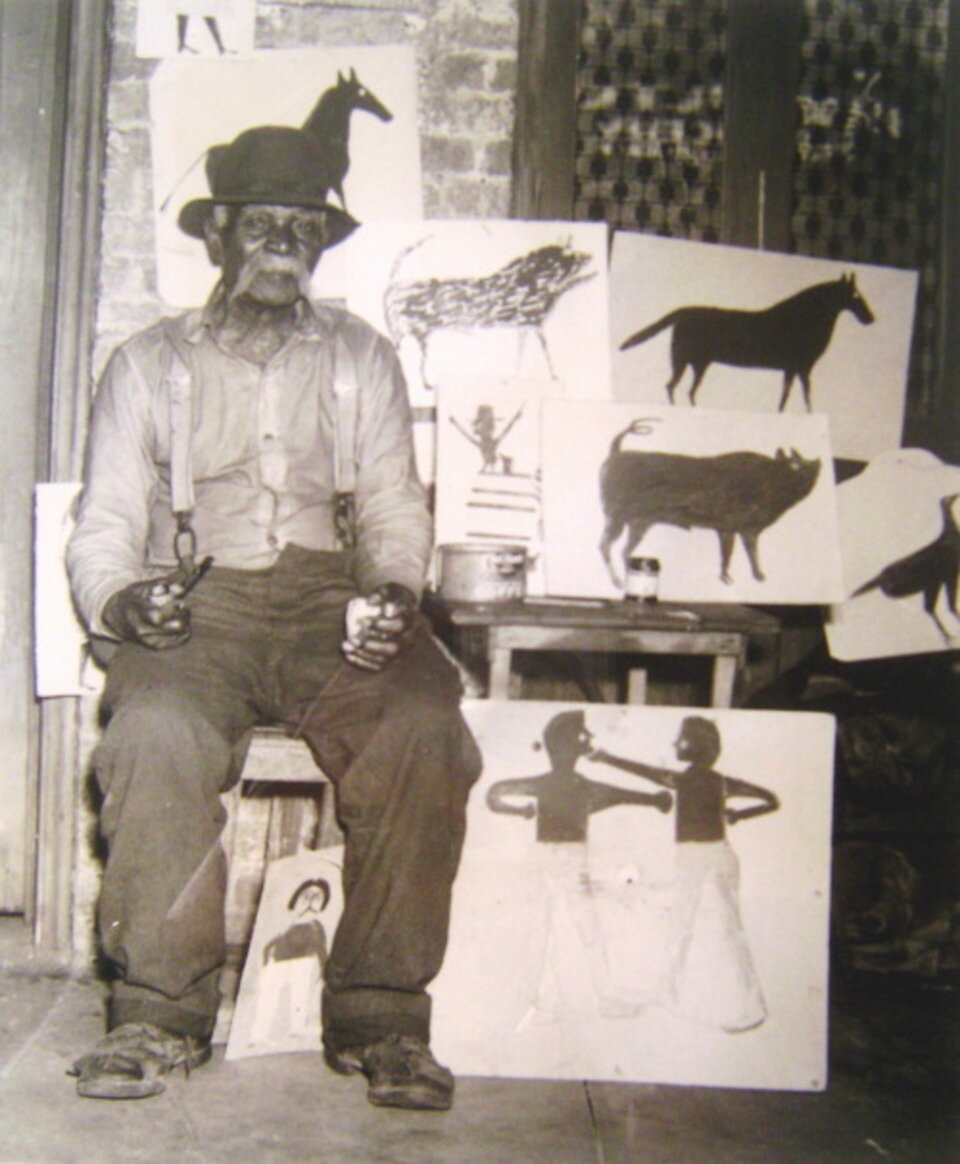

African American self-taught artist who, over the course of three years starting at age 85, created some 1,200 drawings and paintings

Bill Traylor, original name William Traylor, (born April 1, 1853?, Benton, Alabama, U.S.—died October 23, 1949, Montgomery, Alabama), African American self-taught artist who, over the course of three years starting at age 85, created some 1,200 drawings and paintings of people and animals.

There is scant information about Bill Traylor’s youth, but it is documented that Traylor was born in slavery, the son of Bill and Sally Calloway, on the plantation of George Hartwell Traylor. He remained on the plantation after his release in 1863, working as a farm laborer and sharecropper.

Bill Traylor married twice and fathered 13 children, as well as at least two with women outside of marriage. In 1928, once his second marriage had come to an end and his children had dispersed throughout the United States, Traylor, then 75 years old, left for Montgomery, Alabama. Bill Traylor may not have gone directly from the plantation to the city, according to some sources, instead of spending the years between 1909 and 1928 on a farm outside Montgomery.

In Montgomery Traylor worked at a shoe factory. When his rheumatism became too painful, he left his job and struggled to stay afloat. Essentially homeless, he began receiving government assistance in 1936 and found shelter in a back room of the Ross-Clayton Funeral Home, where he slept nights.

Bill Traylor spent his days on Monroe Street, the hub of the black neighborhood in downtown Montgomery. There he drew pictures on any available cardboard or paper. It is widely believed that he began painting in 1939, although he may have started painting a few years earlier.

Using a straightedge and pencils, crayons, charcoal, or whatever he could find, Bill Traylor drew animals, trees, houses, and figures, mostly black but sometimes white as well. These components were rendered flat and geometric, formed from rectangles, triangles and semicircles, and his compositions were devoid of traditional perspective or illusion of space.

Bill Traylor`s pictures reference both lives on the plantation and the activity he observed on the urban street. He drew animals—rabbits, dogs, cows, birds, and others—in profile or pulling a plow or sometimes baring sharp teeth and chasing another animal or a person across the page or up a tree.

His figures, always sporting some accessories such as a cane, pipe, top hat, or purse, appear either static, like silhouettes, or engaged in some activity—drinking, dancing, conversing, or arguing with another person. Bill Traylor introduced all the titles of his action-filled drawings with the words Exciting Event, as in Exciting Event: Man on Chair, Man with Rifle, Dog Chasing Girl, Yellow Bird, and Other Figures.

Many drawings suggest violence and some unnamed antagonism among the animals and figures. Bill Traylor’s unconventional approach to scale often complicated the narrative and relationships within his pictures, when, for example, he would depict an enormous dog being walked by a small person.

Some of the drawings show experiments with abstraction, where limbs and bodies merge with unexpected shapes and compositional elements. Bill Traylor used color carefully (perhaps because crayons, poster paint, and colored pencils were at a premium) and drew simple patterns on clothing and animals.

Charles Shannon, a young white artist, discovered Traylor’s drawing on Monroe Street in 1939. Immediately fascinated by his work, Shannon bought several drawings and began supplying Bill Traylor with materials. In 1940, he organized an exhibition of about 100 of Bill Traylor’s works at the New South Gallery and School in Montgomery.

He organized another exhibit of Traylor’s work in 1941 at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in Riverdale, New York. By 1942, when Shannon left Montgomery to serve in World War II, he had acquired some 1,200 of Bill Traylor’s works.

Traylor left the South for a few years. He lived with his daughter in Detroit and then with other relatives in Philadelphia, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. Possibly, during his time in Washington, D.C., he had his left leg amputated when it developed gangrene.

Bill Traylor returned to Montgomery in 1946, lived for a while with a daughter there, and then moved to a nursing home, where he died. The only known works by Traylor were undated but produced between 1939 and 1942 and are thus all dated as such. Anything that Traylor produced after 1942 was not preserved.

Since the details of Traylor’s life are somewhat vague, scholars and art historians have struggled to interpret his work from a biographical point of view. Having survived slavery, the Great Depression, Jim Crow, and the lynching of his son, Bill Traylor definitely faced many difficulties, and some of them were extracted from the images in his drawings.

Bill Traylor may have had a deep knowledge of the African American tradition of witchcraft (or hoodoo) – folk magic with roots in Africa – and elements found in his drawings could be included as symbols for understanding by other African Americans familiar with this tradition. For example, some drawings include a man carrying a small black suitcase, which would have identified him as a conjure practitioner.

Since Bill Traylor himself was known to carry a black bag, these drawings have been interpreted by some as self-portraits, suggesting that Traylor may have been a master of witchcraft. While Bill Traylor was alive, Shannon did not have much success stirring enthusiasm for his work.

Shannon preserved the works that he bought from Traylor during those three fruitful years (1939–42) and reintroduced them in the 1970s. A turning point in Bill Traylor’s posthumous career was his participation in the 1982 exhibition Black Folk Art in America: 1930-1980 at the Corcoran Art Gallery in Washington, DC. Following this exhibition, Traylor was hailed as a great African American folk artist. The prices of his work skyrocketed and he was included in numerous exhibitions of outsider and folk art.

Bill Traylor is regarded today as one of the most important American artists of the twentieth century.