Between 169,000 and 226,000 years ago, two children in what is now Kesang, Tibet, left hands and footprints on a travertine stone. New research, published in the journal Science Bulletin, suggests that the seemingly deliberately placed now fossilized prints may be the world’s oldest known parietal or cave art.

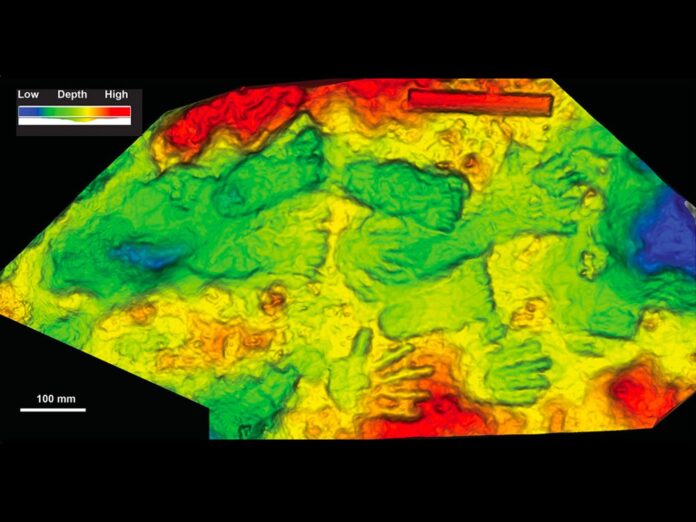

According to the statement, the experts used the dated uranium series to locate the engravings in the Middle Pleistocene. Ten prints – five handprints and five footprints – are three to four times older than comparable cave paintings in Indonesia, France, and Spain.

“The question arises: what does this mean? How do we interpret these prints? They are clearly not randomly placed, ”said study co-author Thomas Urban, a scientist at the Tree Ring Laboratory at Cornell University.

The handprint art discovery offers the earliest evidence of a hominin presence on the Tibetan plateau, write co-authors Matthew R. Bennett and Sally K. Reynolds for a talk. In addition, the couple notes that the results support previous research showing that children were early adopters.

According to Isaac Schultz of Gizmodo, archaeologists discovered a hand and footprints, believed to belong to a 12-year-old and a 7-year-old child, near the Kesang hot spring in 2018.

Although parietal art usually appears on cave walls, cave art examples have also been found on cave ground.

“It is well known how footprints remain during normal activities such as walking, running, jumping, including things like slipping,” says Urban to Gizmodo. “These prints, however, are more meticulous and have a specific arrangement – think more about how a child presses a handprint into fresh cement.”

Given the art hands size and estimated age, the impressions are likely left by members of the genus Homo. Perhaps they were Neanderthals or Denisovans, not Homo sapiens. As scientists note for Conversation, hand shapes are often found in prehistoric cave art.

Early artists usually created handprint art with stencils and pigments, which they placed around the outer edges of their hands. Whether the recently analyzed prints can actually be classified as art, according to the study, is part of a larger “serious debate” about what constitutes art.

Bennett, a geologist at the University of Bournemouth specializing in ancient footprints and paths, tells Gizmodo that the placement of the prints appears to be deliberate: “It’s an intentional arrangement, the fact that no footprints were left by normal movement, and care taken that way. No footprint covers the next, and all of this is indicative of deliberate caution. “

But there are some skeptical experts.

“I find it hard to think there is ‘intentionality’ in this design,” says Tom Metcalfe to NBC News, a paleontologist at the University of Huelva in Spain and a paleontologist at the University of Huelva in Spain. “And I don’t think there are scientific criteria to prove it – it’s a matter of faith and the desire to see things one way or another.”

Urban, for his part, argues that the handprint study highlights the need for a broader definition of art. “We can conclusively prove that this is not utilitarian behavior,” the statement said. “There is something playful, creative, perhaps symbolic about it. This provides an answer to a very fundamental question of what it really means to be human. “

Thus, it can be concluded that a group of fossilized hands and footprints found in Tibet, approximately 200,000 years old, may be the earliest examples of human cave art. And they were made by children.

Every parent knows that children love to dip in the dirt with their hands and feet. It appears to have happened a long time ago in a place where there used to be a hot spring at Kesang, high on the Tibetan plateau, at 4,269 meters (14,000 feet) above sea level.

A report in Science Bulletin suggests that these impressions were made on purpose, not just by wandering around the area. The foot and handprints fit exactly into space and are close together like a mosaic. Their size indicates that they were made by two children, one as large as a 7-year-old and the other as small as 12.

At the time, travertine, a limestone formed by hot mineral springs, formed a pasty mud that was ideal for handprints. Later, when the hot spring dried up, the mud hardened into stone, eventually retaining imprints.

One can interpret whether prints can be considered art or just children playing in the mud, although the authors of the article told Live Science that it could be art in the same way that parents hang children’s scribbles on their refrigerators and call it to cave art. The authors describe the environment the prints are in as deliberately altered, which they thought could be some kind of performance that could be shown, for example: “Hey look at me, I made palm prints on these prints.”