“I didn’t realize until recently what a profound effect he had on my life,” Anthony Rullo said of the Philadelphia-based figurative painter Gilbert Lewis. He first posed for him in 1986, and would do so, about twice a week, for $6 an hour for the next ten years.

At the time, Rullo was 23 and working at a clothing boutique on South Street, which was still a buzzing bohemian and nightlife area. “My life was total chaos,” he recalled. “I was struggling to pay the rent, going out to clubs, and partying.” Lewis’s studio was nearby, and Rullo would come by after work for two-hour sessions. It didn’t even look like anyone lived there. Paintings were stacked all around. The few pieces of furniture looked scavenged from the street. No TV. No answering machine. The artist was only about 41 at the time, but seemed much older to Rullo.

An undated photo of Gilbert Lewis. Courtesy of Kapp Kapp.

Gilbert Lewis always wore a uniform of khakis and a chambray shirt and was almost as broke as Rullo. It confounded Rullo that selling his work was not part of Lewis’s process. He didn’t even seem to try and would deflect any suggestions. “I know that I’m a good painter,” he said to him. “When I’m dead somebody’s gonna find my paintings and then I’ll be famous and I’ll be appreciated.”

Each day, Lewis painted the pendulum of life. He worked as an art therapist in a nursing home. By day, he painted portraits of the elderly, engaging with them as he rendered them.

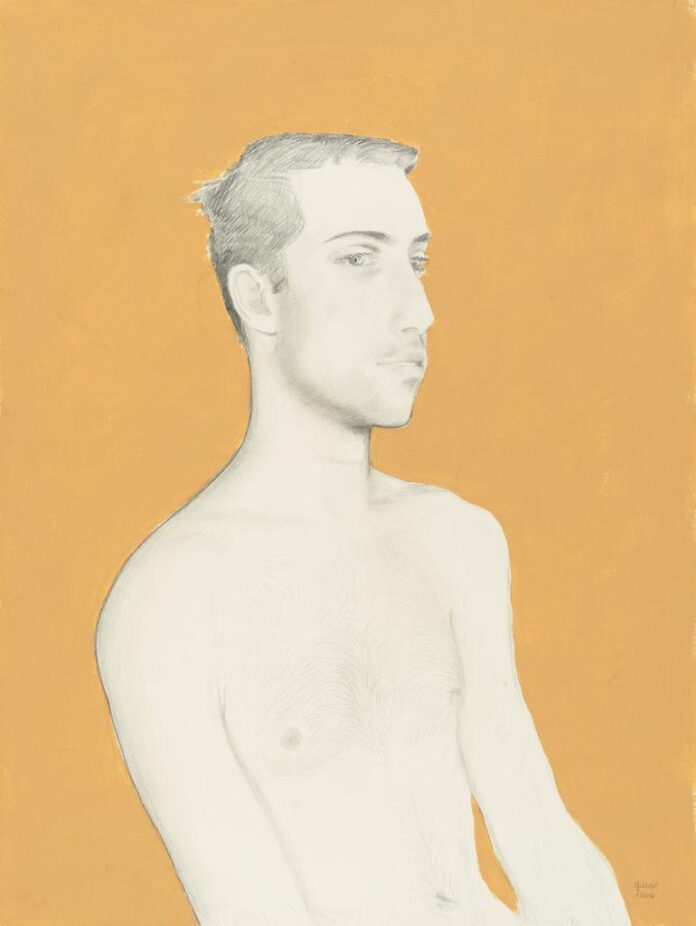

Gilbert Lewis, , September 5, 1984. Gouache on paper, 39 x 59 1/2 in. (Woodmere Art Museum: Museum purchase, 2017)

“One of my motivations in painting has been to celebrate the beginning of adulthood for the young and the final period of life for the old,” Lewis said in a 2004 catalogue interview. “What struck me is that both young men and the old are ignored by society. Despite our ostensible focus on youth, young men are in a sort of nether world, no longer teenagers and yet not full adults. They’re in transition with no established identify and no real place in society.” After work, his salary went to paying the male models who populated his vision.

Both jobs could bleed into each other. “When I’d sit for him, it felt like a therapy session,” Rullo said. “He’d want to know all about you. Going to Gilbert’s was the only thing in my life that was normal, consistent, and calm.” These sessions were reciprocally beneficial to Lewis. Most of the portraits took place in his studio and say as much about the painter as they do the subject, documenting intimate human connection and exchange and a pathway of desire.

Rullo insisted he wasn’t a muse, just one of the legion of models who posed for Lewis. The 60 or so portraits produced over the decade prove otherwise and are a fascinating, varied series. The artist would give Rullo slide images of the completed paintings. Many years later, Rullo lined them up in chronological order.

A selection of the slides Gilbert Lewis would give Anthony Rullo after completing a portrait of him. There are around 60 completed works. Courtesy of Anthony Rullo.

“I could see the trajectory of my life,” he said. “The beginning pictures, I look very young and innocent. And then my attitude toward life changed.” Anthony Rullo was diagnosed with AIDS. “There was no medication, there was no treatment. You could lose your job, your friends, your family,” he said. “I never told Gilbert. You wouldn’t even tell a gay brother or anything. My boyfriend and I and people at that time that were positive, kind of had this ‘fuck it’ attitude. You’d open credit cards and max them out. I’m never paying for this stuff! I was buying expensive clothes, and what I was doing, maybe subconsciously, was creating my legacy. This is how I wanted to be remembered, in these gorgeous clothes. Like I was some important person, which I wasn’t.”

Anthony Rullo wearing a Jean-Paul Gaultier top in 1987. Courtesy of Anthony Rullo.

On the day his boyfriend Keith died in 1990, Rullo went to Lewis’s for a session and the truth came out. “He was shocked. Why didn’t you tell me? For the whole year of 1990, every picture looks like I’m crying. Then over time the next five years, you see another change. By the end I’m doing nude paintings and they’ve become more sophisticated.”

Like much of his work, Lewis’s series of Anthony Rullo is a meditation on male beauty and form. But he also captured the gay emotional condition in the throes of the AIDS epidemic. “But he wasn’t making a political statement,” Anthony says.

Lewis was out-of-step with the straight art world for being too gay, but his longing gaze was anachronistic in the queer art of the time—lacking the transgression and hypersexuality of Robert Mapplethorpe or the clarion militantism of David Wojnarowicz and other firebrands in the Act Up 1980s. The tide has now shifted where the quieter voices from the era are now being recognized.

In an undated artist state, Lewis wrote: “The painting of a face is not just a face. My feelings are expressed through these images. My paintings speak to anyone in touch with their own humanity; to anyone else my art may be dismissed as ‘too personal.’”

Rullo stopped sitting for the artist in 1996 and moved to Miami in 2008. They remained friends and kept in touch until they couldn’t. Gilbert Lewis is in a Pennsylvania nursing facility with advanced stage Alzheimer’s. His large body of work must speak for him, and it seems the world is now ready to listen.

![Untitled [Dennis Dunwoody], December 2, 1981 (L) and Untitled [Dennis Dunwoody], October 10, 1981, by Gilbert Lewis. Gouache on paper. (Woodmere Art Museum: Museum purchase, 2020)](https://static.usaartnews.com/storage/news/dTNRAWQMHYjgmXt23Kn4TOPGv5kwIzezr5tsxHpv.jpg)

Untitled [Dennis Dunwoody], December 2, 1981 (L) and Untitled [Dennis Dunwoody], October 10, 1981, by Gilbert Lewis. Gouache on paper. (Woodmere Art Museum: Museum purchase, 2020)

“The special part of Gilbert’s work is just how contemporary it was,” said Daniel Kapp. “As young gay men just looking around the room, we see ourselves in all of these works.” Earlier this month he was at Kapp Kapp, the Tribeca gallery he co-founded with his brother, installing “Portraits 1979–2002,” the Gilbert Lewis solo exhibition they curated (until February 25). It’s an inspired and intimate primer.

Installation view, “Gilbert Lewis Portraits 1979–2002.” is in the foreground. Courtesy of Kapp Kapp.

Anthony Rullo makes some striking cameos, and the charcoal sketches carry emotional resonance and are installed atop a Gilbert Lewis nautical wallpaper design. Some portraits seem like quick, casual neighborhood visits in his daily painting routine. He’s most compelling when he’s serenely grandiose, as in the languid, sumptuous of 1985 and (1984). The latter is on loan from Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, who presented a solo Lewis show of 49 paintings in 2004 when it was a much smaller institution. It was his first and only solo show in the city, and the museum is the only New York institution to have his work in their permanent collection.

Gilbert Lewis, Untitled (Basking Nude), 1985 Signed and dated ‘5-19-85’ Gouache on paper 60 x 44 inches. Courtesy of Kapp Kapp.

“A big part of why we’re so interested in his work is this anonymity to New York City, at least in the last 20 years,” said Daniel Kapp. “He flew under the radar in Philly too. There really wasn’t a market for his work. The male nude is still not the most popular thing to buy. Lewis had contemporaries working in similar ways in New York, and those artists have gotten more of their dues.”

If the Kapp Kapp show doesn’t garner Gilbert Lewis art world acceptance, it should at least push him into the greater gay canon beyond being a regional luminary.

The year 2020 should have been the year Gilbert Lewis broke into the mainstream. A quadruple blitz of overlapping solo exhibitions in Philadelphia coincided with the pandemic, which limited the impact of the joint efforts at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (“Only Tony” was comprised solely of Anthony Rullo portraits), the William Way Community Center, Kapp Kapp’s prior locale. The Woodmere Art Museum’s robust survey, “Many Faces, Many Figures” captured the painter’s expansive scope.

Gilbert Lewis, Untitled, February 2, 1982. Gouache on paper, 22 1/4 x 30 in. (Woodmere Art Museum: Gift of Eric Barton Rymshaw, 2017)

The Woodmere’s director William Valerio holds the painter in the highest esteem. “Gilbert was thought of in the arts community as one of the major figurative artists working in his time,” Valerio said, “and somebody who managed to define a compelling idea of what realism could be. Historically, the mainstream of the arts in Philadelphia is realism. We’re the town of Thomas Eakins and Charles Wilson Peale. Gilbert Lewis attended PAFA. He went through the curriculum that was designed by Eakins: Paint what you see, paint what you feel, don’t be afraid of your sexuality. It all comes out in his work.”

He continued, “A lot of people have said that Gilbert didn’t achieve the success that he should have because his subjects were perceived to be gay. Gilbert wanted people to pose in the way they wanted, the way they wanted to be seen.”

After getting his BFA from Philadelphia College of Art in 1974, Gilbert Lewis worked at the Aramis cologne counter at the Wanamaker’s department store, which at the time was a gay hotbed. He decamped to New York for a stint at Bloomingdales. It was a disastrous detour. He lived in a hovel, had no money, and was mugged. He returned to Pennsylvania for a career pivot and in 1978 received his master’s degree in Creative Arts Therapy from Hahnemann University (his thesis was “The Spontaneous Art Productions of an Institutionalized Geriatric Population”).

Gilbert Lewis, Untitled (Designer Jeans), 1982 Gouache on paper, 30 x 22 inches. Courtesy of Kapp Kapp.

“Therapists become therapists because they need their own therapy,” said Eric Rymshaw, who met him 1979. “He had an odd, unsupportive family. His father was in the military. They lived near a military base in Norfolk, Virginia. Gilbert’s brother never acknowledged him after he came out.”

Rymshaw and Lewis dated for three years. Art was a lynchpin. “A lot of our time was going to museums,” Rymshaw recalled. “In 1982 we followed David Hockney around the Metropolitan Museum. I wouldn’t go up and say hello. Gilbert loved Hockney. He liked paintings that looked fresh and, didn’t look overworked. Immediacy mattered. So, when Gilbert was painting, it was about what he saw, and immediately putting it on canvas, there were never layers and layers and overworking and reworking.”

Gilbert Lewis, (1984). Gouache on Arches paper, 22 x 30 in. (Woodmere Art Museum: Gift of Eric Rymshaw and James Fulton, 2017)

Rymshaw remembered bringing a lily home from a wedding Lewis wouldn’t attend with him. “Flowers would inevitably go to the studio, he loved them,” Rymshaw said. Lewis spent the following days drawing a series of the bloom decomposing.

“Gilbert painted every day,” he said. “One of the reasons that we didn’t survive was that he so intensely wanted to be in his studio, painting. There was never any time for me. He was always having people come in. He did everything from live models. He never did any photography.”

He added, “Gilbert was sexually driven. I was always very aware that often. I’m sure he had sex with many of the young men.”

Gilbert Lewis, (1987). Gouache on paper, 40 x 48 in. (Woodmere Art Museum: Museum purchase, 2016)

Lewis’s business acumen mixed obstinance with self-sabotage. “He hated commissions. A couple of friends commissioned him to paint their kids and he never finished the paintings.” The artist was a perennial at local art shows and group shows. “He’d always cause a problem by what he chose to put on the walls,” Rymshaw said. “He hated the gallery system and how they treated him.”

Rymshaw would overlap with Lewis socially sporadically throughout the years and remembered Anthony Rullo. “Tony was a fashionista and very much an aesthete,” Rymshaw said. “That was their commonality. I would party with them a little bit, and he met many models through Tony’s social circle. All of Gilbert’s attempts at finding his art seemed to happen through Tony. Whether it was a sketch or finished work, if you put them in a row you can see Gilbert trying out one style to another through Tony and it allowed him to experiment.”

Rymshaw met his current partner James Fulton (the two have an architecture and design firm). They’d buy paintings from Lewis when he’d run out of money, and place some with clients.

Gilbert Lewis in 1988. Courtesy of Kapp Kapp.

Lewis eventually settled down with an abstract painter named Doug Bealer whom he met when he was an art school senior. Doug moved into his sparse row house. Each occupied a separate floor and painted in symbiotic isolation. Their relationship lasted many years. After Doug moved out, he committed suicide about a year later. “That’s sort of when Gilbert started to change, and I think not appreciate life as much,” Rymshaw said.

In 2015, the painter Bill Scott ran into Lewis, who hadn’t shown up at the opening of a group show Scott had recently put him in. Scott greeted him. “He was standing there very politely, kind of with armor on, like he had a boundary. He finally said very politely, ‘Excuse me, but have we met?’ And I said, ‘Gilbert, I’ve known you since 1974.’” Scott contacted Rymshaw and the two began meeting at the artist’s house, which was in a state of severe disrepair, to assist him.

Gilbert Lewis, Untitled (Laying Man), ca. 1980. Charcoal and graphite on paper 22 1/4 x 30 inches. Courtesy of Kapp Kapp.

Even when they were boyfriends, despite being younger, Rymshaw was the caregiver of the pair. That dynamic maintained after their breakup throughout their friendship and would evolve to a higher plane. “I don’t think we actually ever fell out of love,” Rymshaw said. Lewis’s dementia progressed and he had to be moved to a full-time facility. Rymshaw and his husband Jim supported his round-the-clock nursing care for over five years.

Rymshaw became director of his estate, and he and Bill Scott began cataloguing the estimated 400 artworks that filled his row house. For the first time in Lewis’s career, there was a concerted sales effort behind him with funds raised going directly to his care. Many works were donated to museums, such as the Woodmere, to maintain his legacy. “These were important pieces that I didn’t want to end up going into some mysterious collection,” Rymshaw said. Their efforts led to the 2020 exhibitions in Philadelphia.

Scott said of the vast archive, “He was out of step with the world and with the trends. It was like looking at a bunch of portraits by Hans Memling for me. You know how you can look at Renaissance portraits and write ten novels about them from what you intuit from seeing them. Gilbert created a whole world of characters.”