Towards the end of last year, the Wellcome Collection in London decided to close its 15-year-old “Medicine Man” display because it “perpetuate[d] a version of medical history that is based on racist, sexist, and ableist theories and language.” The museum, which predominantly displays medical artifacts, many of which were collected by 19th-century pharmaceutical entrepreneur Henry Wellcome, added that it was in the process of reconsidering “the point of museums.”

With its new exhibition, “Genetic Automata,” the Wellcome Collection appears to be putting forward an alternative proposition for the role of the museum. The presentation features four recent films by the British-Ghanaian artist Larry Achiampong and his long-time collaborator David Blandy, another British artist who is white. Together, the pair explore the legacy of scientific racism and how its ideas still resurface in contemporary culture, technology, and healthcare.

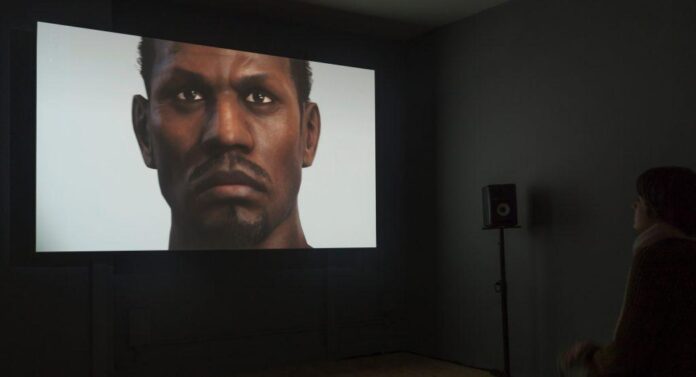

Installation view of “Genetic Automata” at the Wellcome Collection. Photo: Steve Pocock.

The latest film in the series, (2023), was co-commissioned by the museum and the Black Cultural Archives (BCA). Its first half is a direct riposte to the disturbing ideas of Victorian scientist Francis Galton, who established eugenics as a scientific discipline at University College London. The second half, created using Unity, a 3D platform for video games, and littered with references to modern gaming culture, makes an analogy between the myth of genetic superiority and the use of cheat codes to play a video game in the invincible “God mode,” highlighting the comparative lack of agency of “non-player characters.”

A display of related objects includes death masks used by the phrenologist Robert Noel to analyze the different skull measurements of criminals and intellectuals, a “pocket registrator” invented by Galton to secretly categorize people according to five types, and an eye color gauge used in the 1920s for an antisemitic study on the intelligence of Russian and Jewish school children living in London’s East End.

Installation view of “Genetic Automata” at the Wellcome Collection. Photo: Steve Pocock.

These items offer useful historical context to , but the film in turn also gives a new and necessary context to these objects, pulling them out from the past in order to examine their influence on the present.

A particularly successful film, (2020), imagines the perspective of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman who unwittingly became the source for the very first immortalized human cell line, known as HeLa, when her cancer cells were stored after a treatment in 1951. The cells were successfully cloned and sent out to researchers across the globe and have since contributed to many medical breakthroughs, including the development of a polio vaccine. Lacks’s family has objected to the non-consensual harvesting of her cells.

Once more in the style of a video game, large, cell-like forms balloon out from buildings within a eerily dystopian setting. Against this backdrop, we hear Lacks’s imagined voice speak out: “Growing in labs, spliced, injected, and infected for the good of mankind. Your body, swollen to gargantuan form, pulsing, mutating, and splitting, again, and again, and again, as others’ hands manipulate and inspect you,” she says. “Powerless to end this zombie life of your flesh living way past your soul.”

Still from Larry Achiampong and David Blandy, A lament for power (2020). Photo: © the Artists Commissioned by Art Exchange.

“A fortune made of you, and your family has seen nothing, knew nothing for decades. And their genes, through yours, are now visible to all,” she continues. “These riches built on your back. The soil of your cells owned, leased out, and licensed by white men in suits. A legacy for their families. Medicines are made thanks to your body that are then denied to your brothers and sisters for the want of a few notes.”

The final two films are (2019), which tells the little known history of Darwin’s taxidermy teacher John Edmonstone, who was a freed slave, and (2021), which compares the colonial history of archaeology with the modern day practice of mining data to, once again, define people according to categories.

As each film develops, it delves further into the wider social and cultural implications of scientific and medical injustices. The exhibition suggests that “the point of museums” like the Wellcome Collection may no longer be as custodians of a fixed past, confined within glass cases, but as facilitators of an ever-evolving conversation that welcomes new voices.

![The Art Angle Podcast: How the Art World in Ukraine’s Capital Is Fighting Back [Re-Air]](https://usaartnews.com/wp-content/uploads/Jq7M9TtqtdyxxBHMElHBkV8DDCW14GzPHs516Yss-80x60.jpg)