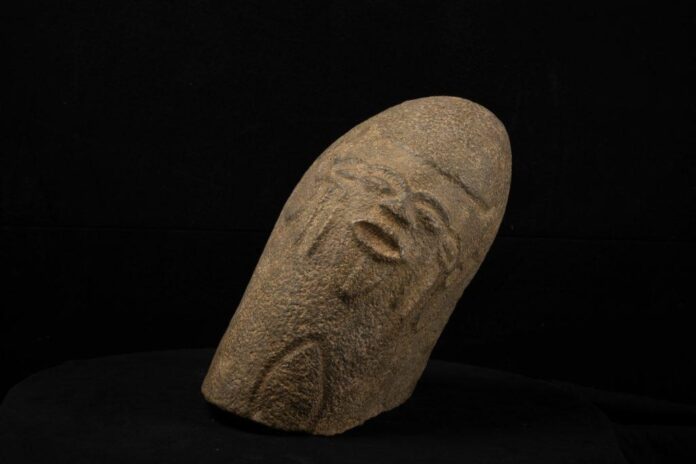

When the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia repatriated a Bakor monolith to Nigeria at the end of June, it did not walk away empty-handed. Instead, it received an almost identical facsimile, only this lightweight version was made of resin rather than basalt rock.

“If you don’t have a trained eye, it’s difficult to tell the difference,” the Chrysler’s director Erik Neil told Artnet News. “It’s really quite remarkable, not just the form but the color and the surface.”

This replica was offered for free by the non-profit Factum Foundation, which specializes in the digital preservation of cultural heritage. It hopes that the exchange may serve as a model for future repatriation agreements.

The Bakor monoliths, also known as “akwanshi,” are stone sculptures that were carved between the 15th and 17th centuries to represent ancestors. They have an important spiritual role within the forest belt of Cross River State in southeast Nigeria. A considerable number have been stolen, with some ending up in Western museums.

Uzoma Emenike, the Ambassador of the Federal Republic of Nigeria to the USA and Erik H. Neil, Director of the Chrysler Museum of Art. Photo courtesy of Factum Foundation.

Nigeria has waged a long campaign for the return of the Benin bronzes and seen major gains in recent years, with a wave of institutions across Europe and the U.S. finally taking action. By comparison, the Bakor monoliths have not received much attention and none had been restituted until last month. Those that remain in Nigeria are unfortunately vulnerable to damage, in particular from bush burning as once densely forested land is redeveloped for agricultural use.

The Chrysler’s monolith entered its collection in 2012 as a donation, having previously been bought at auction for €4,200 ($5,300) in 2005. The museum began to scrutinize its origins more closely this year, after African art specialist Christopher Slogar paid the museum a visit and expressed his concerns.

Further research surfaced a black-and-white photograph from 1961 of the monolith in situ in the village of Njemetop, proof enough that the object was illegally trafficked in defiance of Nigerian law at the time. A spate of these thefts took place during the 1970s, after the Biafran Civil War, and the monoliths were usually smuggled into nearby Cameroon before entering the international market.

The Chrysler wasted no time in contacting the Nigerian Embassy in Washington to arrange a hand-over ceremony. The work will eventually go on display at a Nigerian museum.

Factum Foundation has been digitally recording the Bakor monoliths and producing facsimiles since 2016, developing a close working relationship with Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM). When the foundation learnt of the Chrysler’s decision to repatriate its monolith, their director of projects in Africa, Ferdinand Saumarez Smith, offered to make the museum a facsimile on behalf of the NCMM.

The aim was to pilot a new restitution model, and “show how digital technologies can be used to share objects, so that repatriation is not necessarily a zero sum game,” Saumarez Smith told Artnet News.

He is aware of some 15 monoliths that are currently either held by museums or in the possession of private dealers, with a particularly high concentration in Brussels, Belgium. In 2018, Factum Foundation produced a facsimile of the top half of a Bakor monolith held at the Met in New York, and reunited it with a facsimile of its bottom half, which is still in situ in Nigeria. Other projects of this kind have offered some substitution for real repatriation.

Finishing touches are made at the Factum Foundation workshop in Madrid to a facsimile of the Bakor monolith repatriated to Nigeria by the Chrysler Museum. Photo: © Oak Taylor-Smith for Factum Foundation.

“This time, it was really wonderful to be able to send the original back and the facsimile to the international collection,” said Saumarez Smith. “Lots of these communities thank me when one of the monoliths is brought back in facsimile form, but the original has the spirit of their ancestor inside the stone. So they can do a facsimile of their ceremonies, but it won’t be the real thing.”

Recording the monoliths also has the positive effect of making them much harder to steal and sell illegally. The next step for Factum Foundation and NCMM is to submit the sites of the Bakor monoliths to UNESCO for World Heritage Site status, which would help to protect them from further damage associated with deforestation.

It remains to be seen whether facsimiles can really offer an attractive compromise for museums that are considering repatriating their holdings. The Chrysler is still deciding how to make best use of its new replica, but is sure that its value will be distinct from that of the original items in its collection.

“It comes with its own set of issues,” said Neil. “We’re really trying to make it clear when something is a copy because we want visitors to our museum to be sure that they’re looking at the real thing. I don’t know that we would just integrate it into our gallery of African art.”

“We think it has real value on the educational side because it allows us to continue talking about the function of monuments like this while also opening the discussion about looting and repatriation.”

The complex technological process behind creating the facsimile relies on photogrammetry, a scanning method that makes 3D models by stitching together information from hundreds of 2D images. This digital version is then 3D-printed to get an accurate model that is molded using silicon and then cast in an acrylic resin, with color filled in last. With more time, Factum Foundation could also have produced the replica in basalt.