A very polite estate agent might describe the Landmark Trust’s new property as “a project”. They might say it is “in need of cosmetic updating”. But it is far, far beyond that.

The former RAF control tower will open to visitors in 2025 after a planned £3.1m investment. A fundraising campaign will launch in July with restoration works scheduled to begin in early 2024. But it may startle Landmark regulars, for it promises to be far from the image of the trust’s typical offering. This is not an agreeably eccentric heritage building—a thatched castle, a Grecian temple pigsty or a gatehouse in the form of a giant pineapple—beautifully restored and recycled as a holiday let furnished with distressed leather armchairs, wood-panelled doors and temptingly stocked bookshelves. At RAF Ibsley, the doors are gaping holes in concrete walls.

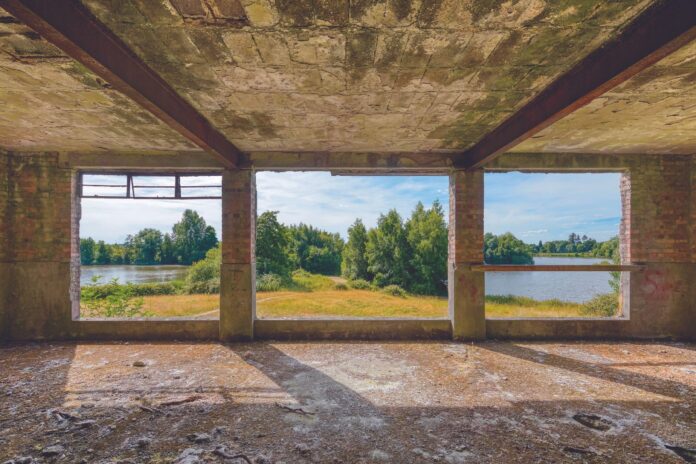

The new property, on which the trust has just signed a 99-year lease from Lord Normanton’s Somerley Estate, is conveniently sited in the heart of the New Forest. It does have a lovely view of encircling trees, a curve of lake with fish leaping and swans gliding past, and huge open skies that are crucial to understanding its history. It does also have several floors, a selection of partial walls and fragments of a Crittall window frame clinging to one hole in the wall. But even Landmark’s buildings team—normally heroically optimistic—describes RAF Ibsley Watch Office as “now dilapidated”.

The abandoned concrete building had been spectacularly vandalised and covered in graffiti.

© John Miller

The building, as far as the trust’s historian Caroline Stanford can determine, is unique. It is a ‘Type 518/40’ RAF watch office; the Americans who later occupied the airfield called them control towers. One of 29 originally built, this is the only survivor with a concrete balcony; the timber balconies of the handful of other examples have long since rotted.

RAF Ibsley was built in 1941, at the height of the Second World War; first as a wooden hut, then, as the air war escalated, as a full-scale airfield, a control centre and a meteorological office. It was built at top speed in pre-cast concrete and was still incomplete when it opened. It was spotted and bombed by the Germans—without casualties—within a month. Local youths were then recruited to apply thousands of gallons of paint to camouflage the three runways; the camouflage may have helped protect the building from attack, but Stanford notes it did not help tired pilots returning in poor light.

The base was later handed over to the US air force, who had to upgrade the airfield in a hurry. It only had elementary communications equipment, with orders for planes to take off communicated by coloured flares and instructions for the landing runway signalled by large numbers shown on the roof. Word of returning planes was relayed as simple codes from a station situated higher on the heaths, where an adopted ginger cat, who liked to sleep on the receiver, invariably heard the distant engines first and gave an earlier warning. It was home to 19 different RAF squadrons over the next three years. The movie First of the Few, starring David Niven and Leslie Howard, a patriotic morale booster that triumphed at the box-office, was filmed there in 1941 while it was still in active service. “It all sounds very Dad’s Army, but it was deadly serious,” Stanford says.

Spectacularly vandalised

After a brief period when the airfield became a motor-racing circuit with the watch office as its clubhouse, the gravel pits around it—quarried after the war—were filled with water, making it a listed wildlife haven today. Meanwhile, the abandoned concrete building was spectacularly vandalised and covered in graffiti. The scars of many parties and barbecues remain, the windows and doors have long gone, and chunks of the ceiling collapsed long ago after rain corroded the metal that reinforced the concrete. The original flat, scrubby landscape is unrecognisable now most of the site is underwater.

RAF Ibsley’s Watch Office

© John Miller

A public appeal is being launched this summer to raise the £3.1m cost of the restoration and conversion, with half of the money already pledged. But this is not just a site of interest for those with a passionate interest in Second World War history. Families all over the world will have a direct connection with the base.

A public house in nearby Ringwood, a favourite drinking hole, was autographed by pilots from countries including Poland, Australia, France and Argentina. Many had their last drinks there; on one mission, 23 planes took off and two came home.

The building is planned to become a four-bedroom holiday home replete with a spectacular first-floor kitchen and dining room with a 180-degree view in the former control room. There will be open days for the general public. Currently, several of the ground-floor rooms are so perilous that they are closed off by accident tape, and one may be permanently out of use because at least one bat—and possibly a colony—has moved in. Mark Cox, the trust’s senior surveyor and project manager, did not even stagger at the news that more large chunks had dropped out of the ceiling since his last visit. He is confident that a high percentage of the original fabric can be preserved. “We’ll be cleaning back all the metal and, as long as there’s enough meat left in it, we can treat it,” he says.

“There is so much history here, from such a crucial period for this country,” Stanford says, firmly. “We must save this building, just at a point where it is still possible to save it. It will be glorious.”