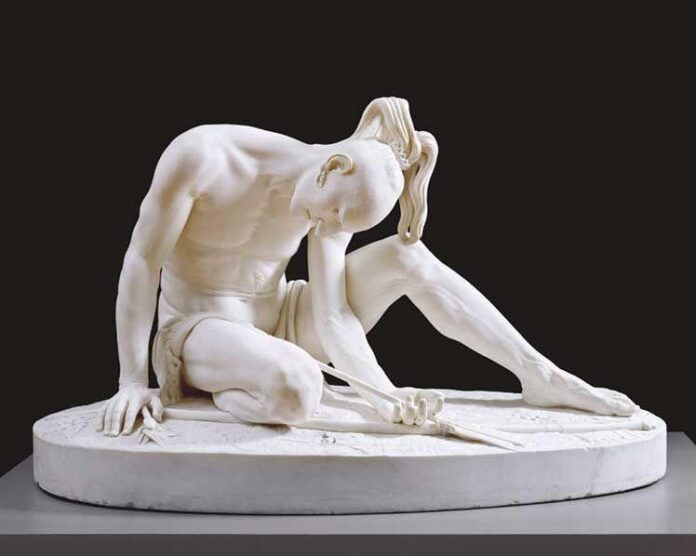

The Wounded Indian, a life-sized marble sculpture of a mortally injured Indigenous warrior, has long been a key work in the collection of the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia. But it is now at the centre of an ongoing restitution dispute.

Modern-day members of The Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association (MCMA), a philanthropic organisation founded by the American patriot Paul Revere in 1795, says that it previously owned and displayed the sculpture for more than 60 years. Revere’s descendants are now claiming the sculpture on show at the museum in Norfolk was stolen, demanding its return and calling for a criminal investigation.

Created around 1850 by the UK-born artist Peter Stephenson, then just 26 years old, the sculpture went on view in Boston, US, notable for being the first life-sized figure made entirely of American marble, mined in the state of Vermont. The native American population had, at that point, largely been displaced west of the Mississippi river, which may account for the sympathetic portrayal of an enemy on the edge of death and no longer a threat.

Stephenson was a promising artist who was raised in the UK county of Yorkshire before learning his craft in Rome, Italy. The work is modelled after The Dying Gaul, the ancient Roman statue now in the Capitoline Museums in Rome. Stephenson crossed the Atlantic to make Boston his home but met a tragic end, dying in 1861, at the age of 37, while incarcerated in a US mental institution. The Wounded Indian came to the MCMA in 1893 after a previous owner sought help to preserve the sculpture.

“It was given to the MCMA,” says Paul Revere III, a lawyer and four-times-great-grandson of the MCMA founder. “If people give you a gift, and they tell you to take care of it and display it for the people of Boston, that’s what you do.”

The MCMA exhibited the sculpture until 1958, when it sold the building in which it was displayed. The work was assumed to have been destroyed when the MCMA’s home was emptied.

Yet the MCMA found The Wounded Indian after a visitor to the association in 1999 said that he had seen the work at the Chrysler Museum. Colleagues who went there learned that the automobile heir Walter Chrysler, whose art collection was donated to the museum, acquired the sculpture in 1986 as part of a collection from the dealer James Ricau. The work is now housed in a gallery that bears Ricau’s name, while a wall panel says Ricau owned the sculpture “by 1967.” Yet there is no evidence of where Ricau got it. “He signed an affidavit saying that he acquired it in good faith. We have no reason to doubt that,” says Eric H. Neil, the director of the Chrysler. “We’ve been very open and forthcoming.”

When first approached by the MCMA, Chrysler lawyers asked why the association had not reported the sculpture’s disappearance, and insisted that it must have been a copy. In 2020, the MCMA and the Chrysler came close to a deal which would have recognised the MCMA’s ownership of the work, sent the sculpture to Boston for a six-month showing, and paid the MCMA $200,000 for legal costs.

The Chrysler rejected paying the MCMA, and still does. “$200,000? I don’t have $200,000 to spare so that someone walks away,” says Neil.

Last year, the museum’s lawyers surprised the MCMA with a box of documents containing written accounts by a Chrysler curator struggling to determine where Ricau might have bought the sculpture—it was proof, for the MCMA, that the Chrysler never got good title to it. “We found out all the information that they hid from us,” says MCMA president Chuck Sulkula. “If that’s the way you want to be, the hell with you—now we want it back.” The MCMA, with no galleries today, would find a place to show it, he predicts.

At the Chrysler, Neil says, “We acted in good faith—that’s our position. There’s no reason in this case to think anything nefarious happened. There still isn’t, actually. If this were stolen, why didn’t they report it being stolen?”

“All the information that the MCMA has comes from us. The glaring gap in the provenance rests with them. What were the circumstances of the separation of that piece from the MCMA?” Neil says. “They say that they had a fire and things were damaged. Does that mean that if the sculpture had stayed with them it would have been destroyed in a fire?”

Neil raised the comparison between The Wounded Indian, on one hand, and unprovenanced Nazi looted art and colonial plunder on the other. He noted that the Chrysler Museum has just sent an ancient basalt monolith lost in the Biafran War back to Nigeria.

As for The Wounded Indian, he said, “Boston in 1958 does not qualify as war-torn. There are no Nazis knocking at the door, there’s no midnight grave-robber. They made a decision to dispose of it. They regret that now, but at the time they may have had very good reasons to do it. There’s nothing forced, illegal or illicit about it.”

Estimates regarding the value of The Wounded Indian run in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, with buyers probably limited to museums that collect mid-19th century American sculpture. If the figure is returned to Boston, it won’t end up at auction, Paul Revere III stresses. “It’s not about having the item and turning it into cash. It’s about the legacy.”

Now the Chrysler may have pushed any potential settlement farther into the future. The museum, which had abandoned its position that the figure was a copy and said the version once owned by the MCMA was the same work now at the Chrysler, has changed its mind once again. “It is clear to me that there were indeed at least two versions of this sculpture and maybe more,” says Neil.

Yet Thomas Kline, a lawyer for the MCMA, says that Peter Stephenson did work with casts, but noted that provenance records show the association never had a plaster copy and that photos document the same damage to the fingers to the marble statue at the MCMA and at the Chrysler. “For director Neil to return to this disproven ‘copy’ storyline is a telling admission of their realisation that law and ethics are not on their side,” he says.

For Neil, that’s still not enough proof: “The fact that we know there were other versions in existence means that we cannot categorically assume that the two pieces are one and the same; it is a matter of possibility or probability but not certainty.”