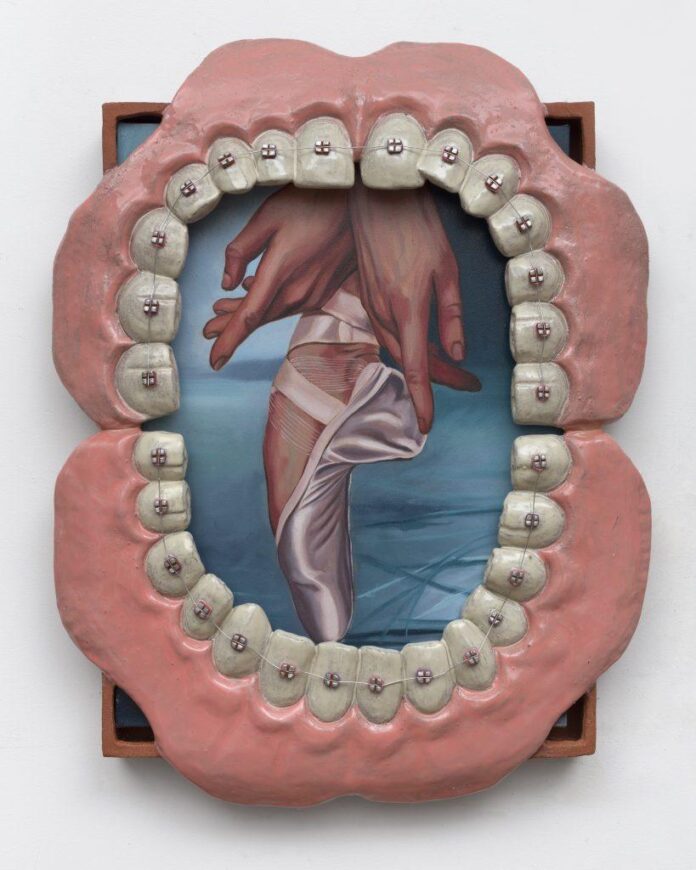

“It’s the flotsam and jetsam of daily life,” said Stephanie Temma Hier, describing the decadent visual contrasts that characterize her artwork. Her works combine three-dimensional ceramic sculptures made in a veritable heap of forms—lobsters, teeth, horses—that frame her glossy, meticulous oil paintings, offering up an uncanny visual tension.

In the backyard of her Brooklyn studio, Hier points to a pile of three car tires she’s found around the industrial neighborhood. She’s using these as molds for an in-progress new series of ceramic tires that will form a sculptural installation for an upcoming exhibition with Montreal’s Bradley Ertaskiran Gallery. Some of the tires will hold paintings in their hubs. “Other elements will be draped over them, I suppose. Some ceramic fish or flowers. Maybe an old teddy bear,” she mused. “There are going to be 30 or 40 ceramic tires.”

Stephanie Temma Hier and her new kiln, 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

She tapped the stack of tires with one hand. “I like repetition,” she said, noting that this will be her largest installation to date.

For the Toronto-born Hier (b. 1992), painting and ceramic elements hold equal weight in forming her witty, surrealistic, and at times disquieting tableaux. These singular creations have earned the artist a devoted collector following. This May, her works were a standout at Independent with Bradley Ertaskiran, where she’s working toward a solo show this fall. She also recently wrapped a solo exhibition “This Must Be the Place” at Nino Mier Gallery’s Brussels location this spring. She also has a show with Gallery Vacancy in Shanghai on the horizon.

With so much in the mix, Hier is abuzz with new ideas as she moved through her studio with palpable enthusiasm and razor-sharp wit. “The studio feels pretty empty after the show in Brussels, but I am filling the space back up quickly,” she said with a laugh.

Material Girl Meets Mad Scientist

Walking through the doors of Hier’s ground floor studio, one is greeted first by her dog Daphne and then by a mammoth, gleaming, stainless-steel kiln that resembles what could be a massive walk-in refrigerator. Genesis, the kiln’s brand name, is emblazoned on one side, conjuring up the biblical creation of Adam from clay, as the kiln is larger than human scale. “This is a major upgrade from the kiln I’ve been using for years and years,” Hier explained, pointing to her old kiln dwarfed beside it. “It’s been a very intense process. These kilns are few and far between. It took six months to manufacture, and it requires an unbelievable amount of power.”

Stephanie Temma Hier and her dog Daphne. Courtesy of the artist.

She points to a tangle of wires. “It’s a learning process,” she said. Hier is self-taught as a ceramicist. She trained as a painter at Toronto’s Ontario College of Art and Design University, but after years of painting, an interest in ceramics emerged organically. She’s learned through trial and error. “I don’t have a mentor I can call to guide me,” she said, looking at the hulking Genesis. “I say I’m self-taught, but I’m on a lot of ceramic internet forums. I would say I’m an internet-trained ceramicist.”

Courtesy of Stephanie Temma Hier.

On shelves beyond the kiln, a few rose-laden ceramic frames are drying. She pulls back the plastic guarding them. “Everything I make is hand-built. It’s very tactile, fitting these elements together,” she said. The ceramics, Hier explained, must be created before her paintings can begin. “I custom-make the canvases to fit perfectly, so I can’t actually start the painting until the ceramic is complete because clay shrinks quite a bit,” she noted.

A beach ball-shaped ceramic hangs against the wall, a circle at its center empty, where Hier will add a tondo-shaped canvas. “Coming from a painting background—and I’m definitely not the first person to say this—but painting has a lot of baggage that can be confining. I like flipping the narrative and letting crafty sculpture dictate the terms of the painting. That’s a satisfying process for me.”

Stephanie Temma Hier, (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Vacancy.

Material freedom is what keeps her ticking. “I’m a huge materials person,” Hier confessed, looking around the studio, and up at a shelf piled with clear plastic containers filled with ceramic pigments. “I can be a bit of a mad scientist with them,” she said, pulling out a notebook filled with handwritten homemade glaze recipes. The glazes, which are sludge-like in their plastic containers, transform when fired to produce unique effects.

“There is a push and pull between control and release, letting the work do its own thing. Painting is so direct. You make a mark and it’s there. It’s not changing,” Hier considered. “With ceramics and glazing, no matter how much testing you do, you can never actually control the process. What happens in the kiln is very organic. Every time I open the kiln, it’s like Christmas morning. I’m always surprised.”

Domestic Consumption and Dead Horse Bay

When Hier moved to New York about a decade ago, she lived in an apartment in Long Island City with a fascinating neighbor, an older musician who happened to be a longtime friend of the Talking Head’s David Byrne and Brian Eno (who had each actually spent time living in the building). “He had all these unreleased tapes of music they had been experimenting with,” she said. “I’d always try to get invited over for a beer, hoping to see what he had, but it never happened.”

Stephanie Temma Hier and her dog Daphne.

Hier’s recent exhibition, “This Must Be the Place,” at Nino Mier is a nod to the Talking Heads as well as her memories of that past apartment. “Brussels’ galleries are in townhouses, so I was playing with that side of my work—intimate personal domestic themes.” For this show, Hier incorporated found objects into her work for the first time, transforming vintage fire pokers, disassembling them, and adding ceramic teeth. She displayed these sculptures next to the gallery’s fireplaces. The show also included a wall work of oversized dinner plates, each with three-dimensional fish and bones surrounding tondo oil paintings of men wrestling, with a homoerotic lilt. An iron, a turkey, and dish gloves all make appearances. In one work, a horse’s body forms a frame surrounding a grid of painted mouths—these expressions included a mix of politicians shouting or people in orgasm—her wry play on the tradition of equestrian portraits. But the culminating work in the exhibition was a ceramic dollhouse. In the gallery, one recognizes miniature depictions of several sculptures installed around the small rooms, a meta-art viewing experience. But in what is ostensibly an upstairs bedroom, a man nods off with a cigarette lit in his hand, fire catching on the bedsheets. As with many of Hier’s works, tension builds between comedy and tragedy.

Courtesy of Stephanie Temma Hier.

Hier, who grew up in a middle-class family (her mother is a dietician), steeps herself in the language of Western consumption and waste, but winkingly—whimsically, even. “I keep my working process very free. I’m really interested in psychoanalysis and the gut reaction that you have to things that don’t necessarily go together,” she explained.

She sources such imagery from across the internet, books, and thrift stores. “I use a lot of vintage cookbooks and print imagery as well. I’m drawn to images or symbols that are loaded with meaning and can be interpreted in a lot of different ways. When I pull them into the lexicon of my work, they bring that meaning along with them,” she said.

One particular place that inspires her is Dead Horse Bay, a strip of marshland in Queens, New York, not far from the trendy strip of Rockaway Beach. Once home to a 19th-century glue factory (hence the name of the bay), the land is a wasteland of abandoned factory detritus. “It’s emblematic of the city that’s been abandoned,” she said. “You can drive out there and collect glass and ceramics, bones, lots of odd little collections. Go out there and tell me what you find. I like to hear what other people discover,” she said.

Stephanie Temma Hier, (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Nino Mier Gallery.

One work in progress for her fall exhibition is a large picnic blanket. Hier encourages me to touch the still-damp clay to feel its still-shifting potentiality. She’s been covering the tasseled blanket with plates and bowls, bones, and ants. She’s strewn all sorts of other trash across it. She notes the art-historical implications of the picnic, calling to mind Manet’s , Kerry James Marshall, a Roman feast—but how they balance with a kind of 1960s dream world, a performance of leisure. “I love the theater of it,” she said. “Art can be so painfully serious. Sometimes we need perspective, a bit of levity. I want to make work that feels important to me, but also, sometimes, work can be enjoyed—that is .”