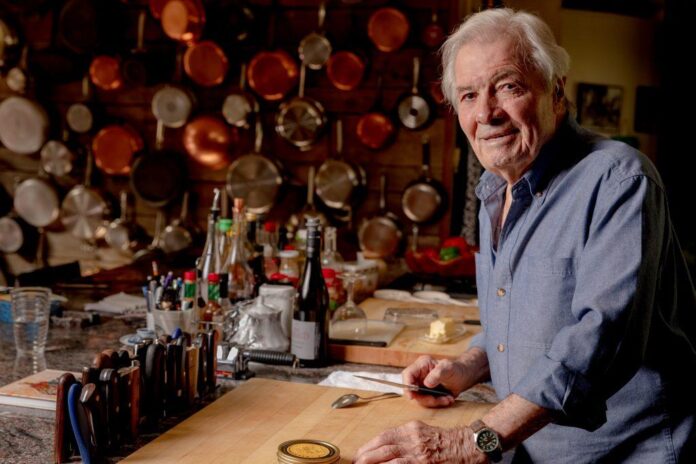

Jacques Pépin surprised fans earlier this year with the announcement that his 32nd book would break from previous recipe collections to feature the celebrity chef’s paintings.

The 256-page volume, , hit shelves last month, and has since become a bestseller.

We spoke with the sizzling savant to learn more about how painting and cooking interact with each other in his career, and why poultry, of all cuisines, inspired his latest creative endeavor. Of course, we peeked the pages in the process to bring you dozens of Pépin’s chicken paintings, from his collection of hundreds.

Jacques Pépin, , 2021.

Out of all the subject matter you could paint, why did you choose the humble chicken over, say, vegetables or flowers?

Chicken is part of my DNA, where I was born in France, Bourg-en-Bresse. It’s a town very well known for chicken, maybe the best chicken in France. So from the moment I was born, until when I was in apprenticeship, I was in the same town, cooking chicken, from the moment you wake up in the morning, listening to the cock raising hell. In France, it’s a symbol.

What keeps chicken interesting to you after all these years?

I could probably do a book of 10,000 or 15,000 recipes of chicken. I’ve been to China, Russia, West Africa—every part of the world—and I don’t know one country that doesn’t use chicken. This is probably the most democratic food.

You took some early painting and art classes at Columbia University in the early 1960s, and you spent some time in Woodstock, New York, practicing your skills. At that era in your life, did you ever think you would publish an art book?

Oh no. I am very lucky that I have a friend here, Tom Hopkins, who did my archive—he’s been working with me for 40 years now doing books.

The first time that I showed some of my paintings was in the library in Stony Creek [New York]—20 years ago, 25 years ago. I went there with my wife. We had some food and some wine to bring, we had all our friends—there were maybe 50 paintings on the wall, and they all went home with one of them. If anyone said, ‘I like that one,’ I said, ‘alright, take it.’ I used to give all my paintings away like that, for years and years.

Jacques Pépin, , 2020.

Do you find there’s a different state of mind that inspires you to pick up a paintbrush rather than turn on the stove?

Cooking is different in the sense that it’s an occupation… It gets less and less complicated. Certainly my younger self tended to add and add to the plate. Over time, your metabolism changes, you take away from the plate to be left with something more essential. If I have a good tomato from the garden with a bit of salt on top, that’s it.

I don’t know whether I could analyze it in the same way for painting, but as you get older your aesthetic changes, your point of view changes. I don’t question myself. I react to some emotion, whether it’s cooking or painting.

Do you feel that expanding your art practice has influenced your cooking at all?

I don’t know. I know something for sure—with the coming of nouvelle cuisine in the ’70s, all of a sudden the chefs started doing everything, plates all decorated, and still that happens at three-star restaurants. I never really followed that… I like a plate to be nicely presented, but very naturally.

For me, the most important thing in food is the taste. If it looks good, great, but it’s not absolutely essential. The aesthetic of food itself, I never really emphasize it much. Of course it’s different in painting, but to a certain extent I don’t know exactly where I’m going when I start. I have an idea, but sometimes it starts changing. Eventually at some point, usually, the painting will take a hold of me and I react to it. I put that color here, that shape, because it looks good, it feels good. I don’t know whether it’s good or bad. I just react to it.

Jacques Pépin, , 2020.

How do you judge the success of a dish versus the success of a painting?

This is different than painting, because you always cook for someone else. It’s a great act of love in a sense to cook for someone else. You always cook to please someone. If I have a rack of lamb on the menu, and if no one said anything, I will do that rack of lamb the way I like it—that is, medium rare. But this is not the way that people always like it—some like it well-done, or very, very rare. I do it the way they like it, because to cook for someone is to please someone, not to please yourself.

Then how do you know if a painting is successful?

I never know whether the painting is successful… Actually it’s pretty important to know when to stop, too. The same thing with a dish—you can continue cooking something and adding and adding, and all of a sudden you blew the whole thing. You have to know when to stop.

It is interesting for me to look at paintings that I did 15 years ago and think I would never be able to do that [now]. Does that mean that it’s good or bad? It just means that I don’t feel the same way, I would not use the color in the same way.

I would absolutely love to be able to taste food that I did 50 or 60 years ago. Food of course is very evanescent… with a painting, you can look back.

Jacques Pépin, , 2017.

What do you hope longtime fans and new dilettantes get from your book?

This is a different type of book. I did a book called The Apprentice 20 years ago, and it was a memoir. But since I have 31 books on cooking, I asked my publisher [about doing this book] and, as soon as they saw a painting of a chicken, they said, ‘Can we have recipes with it?’ I said, ‘I don’t want to do recipes.’ That’s not the idea, the idea was for me just to do a book.

Finally we decided that I would do a story, just like I did in The Apprentice, but about chickens and eggs from when I was a kid. The recipes are in narrative style. Some of the recipes you can probably do; other ones are not doable because they were done in the old style, using an unborn egg, sweet bread, all kinds of things that people don’t use anymore. For me, this book was totally different. It wasn’t a cookbook and it wasn’t an art book only. It was a mixture of both. I thought it could be a real flop. People would say, ‘What kind of book is that?’ But apparently it’s been pretty successful. I’m surprised, to tell you the truth.

What artists inspire you?

The Impressionist period, from Monet to Manet, and even Picasso, because of his complexity and being so good at so many different ways of looking at things. But I’ve been told many times that I have no style. I love to do flowers and some abstraction, and of course chickens. But I don’t think I have a style.

Jacques Pépin, , 2019.

Is that what you like about impressionist painting too, that open-ended potential?

Yes—this is why I like to do flowers. Flowers for me are the perfect medium between abstract and representational painting. I start on a canvas applying a batch of color, very abstract in a sense, and eventually taking the form of a bunch of flowers. It’s a good foundation for me.

What’s next for you?

I have another book coming out next year, a book of recipes this time. Next week I’m going to Austin, Texas, the week after that to Florida, to Amelia Island, to play Bocce in a competition. Then I’m on a cruise during Christmas [serving as a culinary director] in the Caribbean.

More Trending Stories:

Click Here to See Our Latest Artnet Auctions, Live Now