The long-established trade in Old Masters faces plenty of challenges in today’s globalised, digitised art market. The biggest of all, as ever, is finding desirable pictures to sell.

With war waging in Ukraine, and inflation and interest rates rising across the world, there was a clear tightening of supply at the latest summer series of high-end Old Master auctions in London. On Wednesday evening, Sotheby’s raised £7.1m from a slimline mixed-owner offering of 20 lots that took just half an hour to sell. Sotheby’s equivalent pre-pandemic auction in 2019 grossed £56.1m from 37 lots.

“Short on quality, short on interest,” says Nicholas Hall, a dealer in Old Master paintings based in New York, commenting on Sotheby’s Wednesday evening auction. Last month at the rescheduled TEFAF fair in Maastricht, Hall confirmed the private sale of a rare circa 1495 Vittore Carpaccio panel of the Virgin and Child With Saints Cecilia and Ursula, with an asking price of between $10m and $15m. “It’s a gamble selling at auction, and people don’t like the odds at the moment,” adds Hall, a former specialist at Christie’s.

The Netherlands-based Kramer-Lems Foundation’s gamble of offering an impressive Willem van de Velde the Younger seascape to fund the purchase of a 1718 Stradivarius violin didn’t pay off at Sotheby’s. Estimated (but not guaranteed) to make at least £4m, The surrender of the Royal Prince during The Four Days’ Battle, 11–14 June 1666, was the stand-out lot of the evening, but failed to draw a bid. Ten years earlier, it had sold at Sotheby’s, London, for £5.3m.

Ludolf Backhuysen’s A States Yacht and other Ships on the Sea in stormy Weather (1675) sold for £730,800 to a telephone bidder at more than three times the pre-sale estimate Courtesy of Sotheby’s

With the star lot flopping, Sotheby’s main success was the fine signed and dated 1675 Ludolf Backhuysen canvas, A States Yacht and other Ships on the Sea in stormy Weather, that had been in the same Dutch collection since 1964. This sold for £730,800 to a telephone bidder at more than three times the pre-sale estimate.

It was a similar story with the small, ethereal Fragonard canvas, The Fountain of Love (around 1784), which hadn’t been on the market since 1988 and sold for £718,200, again on the telephone. “It was a bargain,” says Hall, who was one of several underbidders.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Fountain of Love (around 1784) sold for £718,200 Courtesy of Sotheby’s

“Good material has become increasingly difficult to find,” says the Amsterdam-based art adviser, Johan Bosch van Rosenthal. “Being able to present a good auction has increasingly become dependent on discoveries and what is left in old family collections,” he adds, pointing out how the auction houses are having to pad out their Old Master offerings with sculptures and prints.

Given the various headwinds currently faced by the trade in Old Masters, particularly in post-Brexit London, dealers were impressed by the material Christie’s managed to gather together for its auction on Thursday evening.

The Christie’s sale was anchored by two museum-quality rarities from the collection of the late British philanthropists, Cecil and Hilda Lewis. Boosted by these prime lots, Christie’s 36-lot sale raised £28.1m, almost twice the £14.9m its equivalent mixed-owner sale achieved in July, 2019.

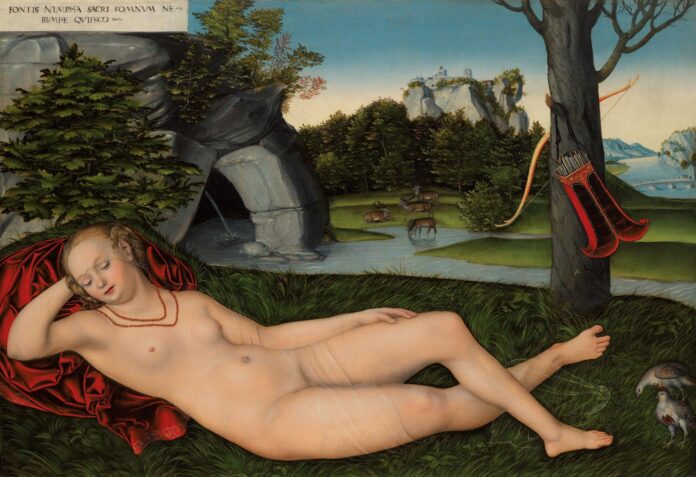

Lucas Cranach the Elder’s early 16th-century Nymph of the Spring was one of at least 12 known variations by the German artist on the theme of a reclining nude in a landscape. Owned in the 17th century by Queen Christina of Sweden and never offered at auction before, this impressively large version enthused at least five telephone bidders, resulting a price of £9.4m, an auction record for the artist.

The same family collection yielded a superb signed and dated 1633 still life on panel, Pewter Jug and Silver Tazza on a Table, by the enigmatic and little-heralded Amsterdam painter Jan den Uyl, whose reputation rests on only about a dozen works. Like the Cranach, this hadn’t been seen for more than 30 years. It sold to a telephone bid of £3.1m.

Anton Raphael Mengs’s portrait of Friedrich Christian, Prince of Saxony (1722-63) sold to the the London dealership Agnews for £475,000 CHRISTIE’S IMAGES LTD. 2022

Canova’s recently rediscovered “long-lost masterpiece,” The Recumbent Magdalene (around 1819-22), was in too weathered condition to find a buyer at £5m and went unsold, but there was plenty of competition for a spectacular Anton Raphael Mengs’s portrait of Friedrich Christian, Prince of Saxony (1722-63), who was the son of Augustus II the Strong. The sitter wasn’t exactly classically handsome, and Mengs isn’t the most famous art historical name, but dealers recognised the exceptional quality and condition of a painting that had seemingly remained in the same family since its original commission. Estimated at £100,000-£150,000, it sold to the the London dealership Agnews for £475,000, unusually, for stock. While hardly a “sleeper,” Anthony Crichton-Stuart, the director of Agnew’s, thinks this is a work with the potential to appeal to a museum. “We feel there’s a lot more to be learned about this painting. Mengs was an important figure in Europe, and it’s in fabulous condition.”

These sales at Sotheby’s and Christie’s show that somehow the auction houses continue to unearth Old Master rarities that keep business bubbling along. But these days it’s a struggle for both houses to do so in the same week.