The blowing up of the Bamiyan Buddhas in March 2001 has long stood as a symbol of the barbarity of the Taliban. However, there is unexpected evidence that the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA), the Taliban government in power since August 2021, is showing respect for Afghan cultural monuments, including pre-Islamic ones, and is aware of their importance to the country and in the eyes of the world.

On 13 March, a meeting was held at the Kabul Museum attended by Taliban officials and museum staff. The proceedings were in Pashto, so it was not directed at an international audience.The sole Westerner present was Jolyon Leslie, an advisor to the Afghan Cultural Heritage Consulting Organisation (ACHCO), an independent entity funded by international donors such as the Aliph Foundation. He says that in the course of it, Zabihullah Mujahed, the leading spokesman for the IEA, expressed regret at having failed to protect the cultural heritage in the past, while not mentioning the Bamiyan Buddhas explicitly.

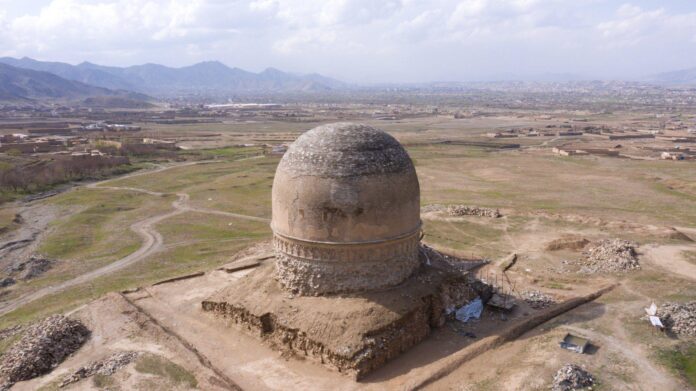

Leslie says that shortly afterwards the IEA’s deputy head of culture, Mawlawi Aliqullah Azizi, visited Shewaki in eastern Kabul, the second biggest Buddhist stupa in Afghanistan, currently being restored by the ACHCO. Azizi sat down with the Afghan craftsmen working on it and asked them what it meant to them. Leslie reports that Azizi then said that the government intended to go on supporting the conservation of this site.

Leslie knows Afghanistan intimately. He is a British conservation architect who has been in the country since the early 1990s, working for the UN from 1996-2000 under the first Taliban regime and then managing the programme of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture in Afghanistan. He travels widely in the country and speaks fluent Dari. Leslie says that the government’s interest goes beyond the physical preservation of monuments; they are fascinated by Afghanistan’s pre-Islamic past and have asked ACHCO to do more work on Buddhist sites and provide translations of texts about them into Dari and Pashto.

This does not square with the many articles that have accused the Taliban of allowing looting at the site of the Bamiyan Buddhas and inappropriate buildings to go up in front of the empty niches. Leslie says, however, that there is a long history of inconclusive interventions in the valley, and, while the new bazaar is worrying in its form, “it is probably driven by a wish by the current authorities to be seen to be doing something”. He adds that “Unesco has spent a fortune over the past decades on a series of ‘master plans’ for the valley, with little idea of how these might actually be realised”. He says that lucrative and illegal development has been going on in the valley for decades and that the Unesco plans for the valley have largely come to nothing.

The ancient Buddhas of Bamiyan, the sculptures in Afghanistan that were built in 507AD and 554AD, were the largest statues of standing Buddha on Earth until the Taliban blew them up in 2001 Photo: US Army / Sgt. Ken Scar, 7th Mobile Public Affairs Detachment

An anonymous senior figure at the Aga Khan Trust for Culture confirmed the Taliban’s current interest in preservation. He said that people from the trust—an arm of the Aga Khan Foundation, a private, not-for-profit international development agency—are going around the country documenting sites and that they are not seeing deliberate destruction of anything. “The Taliban are intelligent and know what is of interest to Westerners. They learnt their lesson from the Bamiyan Buddhas and were in favour of protecting the tangible heritage even before taking over in 2021”. Looters and illegal excavators are being punished, as with the arrests at the Hellenistic and Khushan site of Zargar Tepe in Balkh Province, according to the Aga Khan Trust.

The Taliban are, however, a precarious balance of affiliates often at variance with each other and what is decided in Kabul is not always respected in all parts of the country. In addition, the government must contend with the destabilising efforts of the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) based in the east of the country. This affiliate of Isis is hostile to the Taliban government’s attempts to normalise the administration of the country and practise relative religious tolerance, and it makes itself felt with terrorist actions such as the powerful explosion at a Sufi mosque in Kabul last month.

The world’s nations, led by the US, have refused to recognise the Taliban regime, which is, however, giving some proof of evolution from a guerrilla force to mastering the modern requirements of administration. This refusal affects all aspects of life, including the cultural. For example, in Kabul there is the early 16th-century Babur Garden—with its roses, pavilions, water channels, and cascades, the only surviving example in the early Persian and Timurid tradition—which has been restored over the last 20 years by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture in Afghanistan. It is a precious, free resource in a stressful city, enjoyed by hundreds of thousands of Afghans with the approval of the Taliban. An application was made to Unesco in 2009 for World Heritage Site status but it did not go forward because of the threat under the previous regime of uncontrolled development around the garden’s perimeter. Now the obstacle is that World Heritage Site status can only be granted to a member state, so until Afghanistan has a recognised government, it cannot happen.

The Taliban are trying to run a country where the economy has nearly collapsed due to the withdrawal of Western aid and the economic sanctions imposed mainly because it has not kept its promises regarding the rights of women. Large areas of the country are suffering from great hardship and famine. This means that it has tough choices to make, such as at Mes Aynak, where the Chinese want to extract a rich seam of copper. But this is also a 5.5-hectare Buddhist site and the question is, which will the government put first: the chance to earn hard currency so that it can pay for basic services, or the chance to preserve the relics of the past? The sanctions on Afghanistan are not only affecting the lives of Afghans today, but may also affect what survives of the people who have lived here over the centuries.