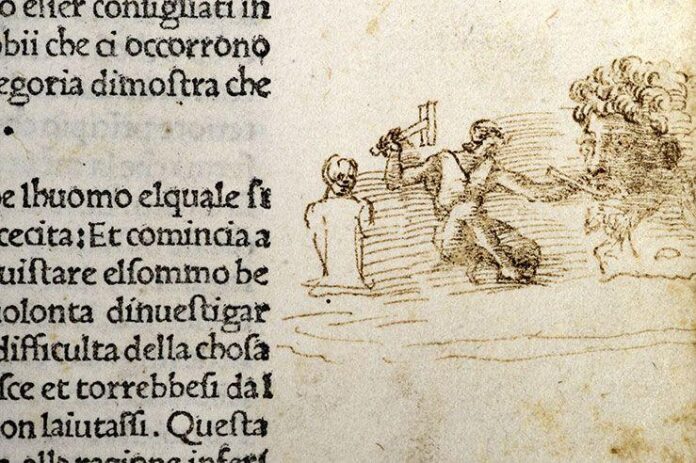

A drawing nestled in the margin of a 15th-century edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy shows Michelangelo at work, says the author and scholar James Hall who researched the sketch for his new book, The Artist’s Studio: A Cultural History (Thames & Hudson). “The sculptor, hitherto unrecognised, can only be Michelangelo during or shortly after his triumphant achievement carving the David (1501-4),” writes Hall.

Hall’s interest in the illustration was piqued at a lecture on the Dante book given by Bill Sherman, the director of the Warburg Institute in London, a centre for academic research into the Renaissance. “I briefly saw this amazing drawing at the lecture. I wondered if I might include it in my book. After several months, I suddenly thought that a lot of the pieces of the jigsaw seem to fit Michelangelo,” Hall says.

The drawing shows an artist at work sculpting a colossal head, wielding a mallet. An armless statuette stands behind him. “You don’t usually get something that looks naturalistic and human which is telling an extremely interesting story, illustrating a simile in Dante,” Hall tells The Art Newspaper. The drawing appears in the first canto, Inferno, at the point when Dante boldly decides to take the “high path” through Hell.

The sculptor has abandoned the more frivolous statuette to carve the colossal head. “Its head seems to be turning over the shoulder, with a smirk. I think it’s supposed to be a faun,” says Hall. “It reminds me a lot of the faun clinging to the leg of Michelangelo’s Bacchus (1496-7). Also, on the Sistine ceiling, there are decorative putti [cherubs] fixed on to the architecture flanking the prophets and sibyls [oracles], who are similar, turning with cheeky expressions on their faces; it seems very much in that spirit,” says Hall.

Crucially, the colossal head is similar in appearance to Michelangelo’s statues of St Paul and Peter (1501-4), made for an altar in Siena cathedral. “The heads are very classical in style and that also fits the Dante passage where, still hesitating, he says, ‘I am not Aeneas, nor St Paul.’ So Dante is saying I’m not one of these great figures,” Hall says. “But that is what he becomes when he enters Hell. So too Michelangelo when he makes vast works that surpass antiquity.”

The artist behind the lively drawing is the subject of debate. “The Dante edition was thought to belong to the Sangallo family who were architects and sculptors, mostly based in Florence and Rome. But recently that has been questioned because the handwriting of the annotations in the book does not seem to match up with the Sangallos,” he adds.

A Tuscan artist or even a talented amateur could have created the Michelangelo depiction, Hall adds. “It would have been a labour of love; whoever had this book would have gradually annotated it over the years. In this drawing, you see different styles: the faun is made in a lightly drawn linear style whereas the rest of the drawing has got lots of shading. What makes the style particularly unusual is the way the artist fills in the background with parallel hatching, a technique sometimes seen in the prints of [the 15th-century artist] Andrea Mantegna.”

The Artist’s Studio: A Cultural History, James Hall, Thames & Hudson, 288pp, hb