Hilary Bourne’s name is displayed proudly in Ditchling, the Sussex village where she was brought up and taught to weave by a neighbour. It is on the foundation plaque of the lovely crafts and local history museum she founded with her sister Joanna in 1985 and on a beautiful curtain she wove for a local church. But the Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft is only now restoring the missing name of Barbara Allen, Bourne’s partner in work and life, in an exhibition celebrating their achievements—not just as weavers, but as pioneering Modernist artists and designers.

As their research developed, fashion historian and curator of queer culture E-J Scott and textile historian Veronica Isaac were increasingly struck by how often Bourne and Allen’s names were missing from the record. They made textiles for the upscale London stores Liberty’s, Heals and Fortnum & Mason, winning glamorous and prestigious commissions, yet their work was rarely credited. They wove hundreds of yards for the 1959 epic Ben-Hur, a task so challenging they initially quoted an outrageous price, thinking MGM would refuse. The duo got the job and created the Hollywood star Charlton Heston’s costume, but the Oscar, and the credit, went to costume designer Elizabeth Haffenden.

A fabric sample, woven by Hilary Bourne, that was made for the actor Charlton Heston to wear in the 1959 sword-and-sandal epic Ben-Hur Tessa Hallmann for Ditchling Museum of Art and Craft

In 1951, Bourne and Allen created spectacular textiles for the Royal Festival Hall, the jewel of the Festival of Britain, which was celebrated by The Architectural Review in a special issue. In tiny letters on the inside back page, among hundreds of other names, it lists “Hilary Bourne and Barbara Allen: Fabrics”. A two-page spread is devoted to photographs, plans and a fabric sample for a meeting room; the captions mention a giant curtain, designed to be viewed from either side as a room divider, but the only name listed is Robin Day’s—for the furniture. Another Bourne and Allen fabric sample is seen in a spread of the foyer, again uncredited. A charming photograph of the 25-year-old then-Princess Elizabeth at the opening shows the royal box lined with yet another beautiful but anonymous curtain.

Unsung heroines of textiles

If Bourne and Allen were hurt by these omissions—after attending the opening reception using stripy tickets they had also designed—there is no record of it, as with so much of their lives. Staff at the Royal Festival Hall, when asked for any additional archival material, responded that they thought the textiles were designed by Sadie Speight, wife of Leslie Martin, joint architect of the hall. (Fortunately, samples survived and will be in the Ditchling exhibition.) When the Royal Festival Hall reopened in 2007 after a £111 million restoration, the Bourne and Allen textiles were not recreated.

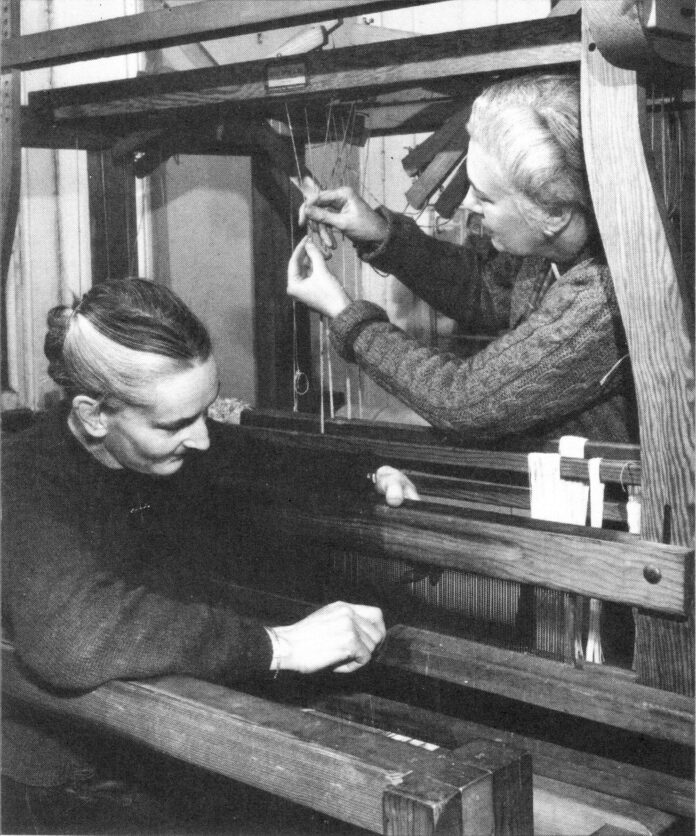

Scott and Isaac (who have co-curated the exhibition with textile, dress and women’s historians Jane Hattrick, Shelley Tobin, Jane Traies and Suzanne Rowland) have found only fragments about the pair in Bourne’s scrapbooks—the Evening Standard mentions they had recently woven “furnishings for a wealthy American’s yacht”, so far untraced. There’s a lovely photograph in the Eastern Evening News of the pair at their loom (above), noting their usual output is just three yards a day, and a short interview relating that they weave and make their own clothes, “which never wear out”.

Neither Bourne or Allen come up if you search the websites of the Crafts Council or Arts Council England. The Victoria and Albert Museum’s site does have references to Bourne, with four pieces of fabric hosted in its Textiles and Fashion Collection.

The absence of the spotlight on their work, Scott believes, is plainly due to Bourne and Allen being not only a professional team but also a couple. Given the era, this fact could not be revealed, let alone celebrated. “Where is the evidence for queer couples? There are no marriage certificates, no eulogies at their funerals, no children. They are just missing from the records,” Scott says. “But they were there, and it is our job to bring them back into the light.”

Bourne was born in India in 1909 (d. 2004) but when her father died, she came with her family to Ditchling—then the centre of a remarkable group of artists and designers, including the now disgraced sculptor Eric Gill. Allen was born in Croydon in 1903 and initially worked as a stage designer. The two met at Westminster Theatre in Victoria and were together for almost 40 years. Scott says they were supported by a network of women artists and galleries—whose importance in the history of British 20th-century art is only now being unravelled—and accepted as an unstated couple, living together and sending and receiving joint Christmas cards and presents. When they managed to save enough money, they travelled widely, often learning new techniques and collecting beautiful textiles. In 1972, they stayed overnight in a hotel in Cambridge before an overseas adventure. A fire broke out. Allen died, and Bourne was left injured and emotionally devastated. She sold their house in Yorkshire—destroying a mass of records, to the despair of present-day researchers—and returned to the south to spend the rest of her life in Ditchling.

“When Hilary and her sister created this museum, it was surely partly as a memorial to Barbara—but even then, this couldn’t be stated openly,” says Isaac.

“You find a mention here, a mention there, but this is just the starting point, the first delve into their history. There are years of work still to be done.”

“Even where they are being remembered, they are being separated,” says Isaac. “We want to put that right.”

- Double Weave: Bourne and Allen’s Modernist Textiles, Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, 16 September-14 April 2024