Helena Schjerfbeck, one of Finland’s most famous artists, is surprisingly little known outside her country. Her unique paintings will now be on display in a major exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. This is an opportunity for us to learn more about the life and work of a woman called the “Finnish Munch”.

Schjerfbeck was purposeful, ambitious, prone to recluse, but at the same time a great fashionista. The pinnacle of her work – the self-portraits she created throughout her life – was a study of mortality, which connects the artist with Goya, Rembrandt, Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud.

Helene Schjerfbeck, “Self-Portrait on a Black Background” (1915). Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki.

The “Face” of the retrospective in London was a self-portrait ordered in 1915 by the main Finnish museum Ateneum. The institution was preparing an exhibition in which Schjerfbeck was the only woman (she was not a militant feminist, but supported the right to vote for women – Finland was the first European country that gave women such a privilege).

In the resulting painting, the artist made herself a blush mask and put a bright red paint cistern next to it, and in the background painted her name in the Golbein style.

Helena Schjerfbeck was born July 10, 1862 in Helsinki. It is said that her artistic life began when at the age of four a girl fell from the porch and broke her hip. A badly compounded fracture left her limp for life, but during her recovery her father gave her pencils, and she started drawing (isn’t that reminiscent of Frida Kalo’s story?). Later on, Sheurfbeck said: “When you give a child a pencil, you give him the whole world.”

The talent of the girl was discovered by her teacher when she was 11 years old. She got a scholarship to the Finnish Art Society’s drawing school in Helsinki. Two years later, her father died of tuberculosis. The family could never boast of wealth – Svante Schjerfbeck started as a merchant, went bankrupt and became the manager of a railway workshop. His death further undermined the family’s budget. Olga, Helena’s mother, took guests and sewed to make ends meet. But she never considered painting a suitable career for her daughter. Young Helena was supported only by her father.

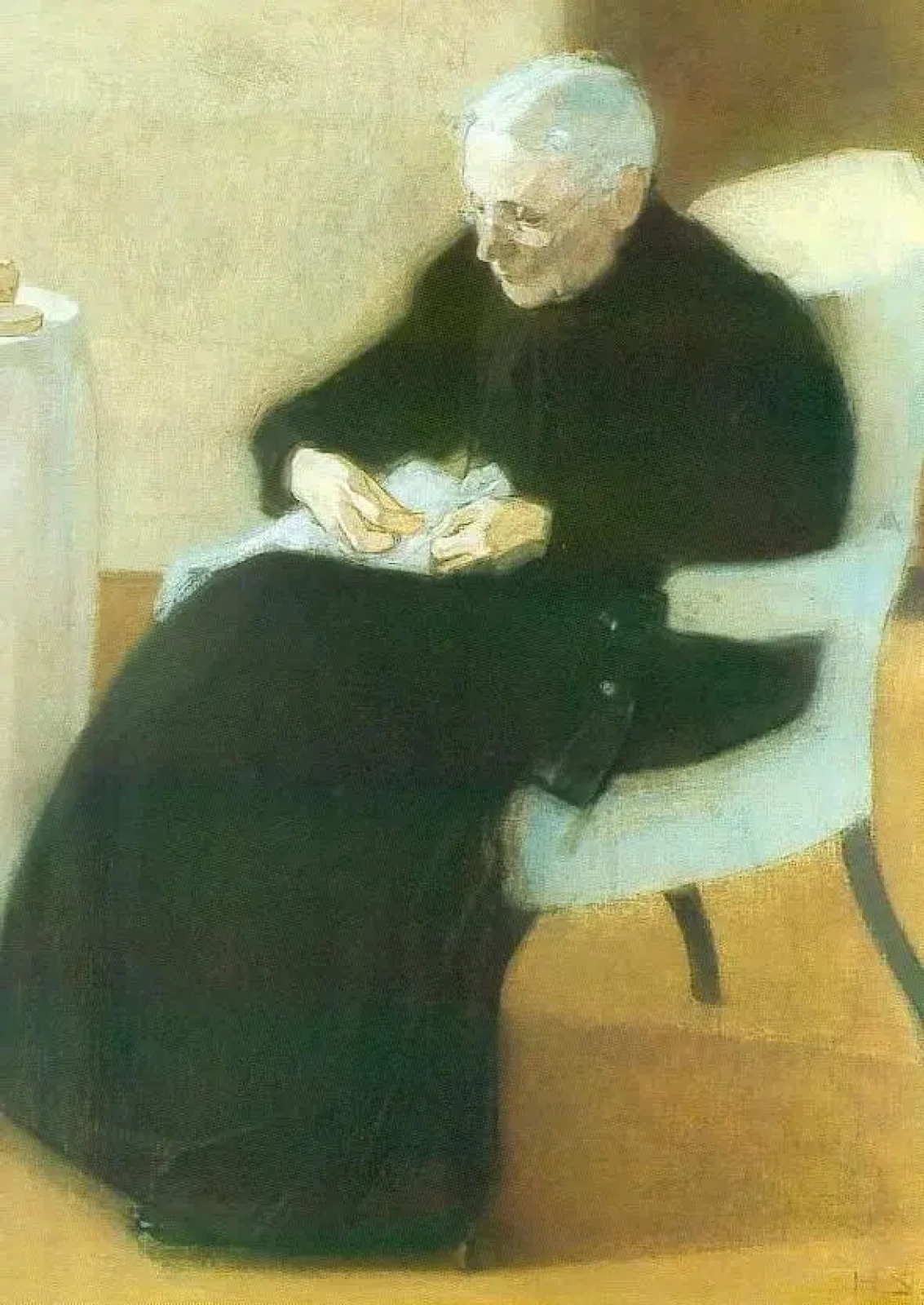

Helena Sofia Schjerfbeck

1912, 43.5×42 cm

Fortunately, help has been found. The girl was given an additional scholarship to promise oil painting at the Academy of German artist Adolf von Becker from 1877 to 1880. In 1880, 17-year-old Helena painted a picture that marked the beginning of her career – “Wounded soldier in the snow”, characterized by carefully considered naturalism. At that time, the military theme without aggression was rare, and female artists more often painted floral still lifes.

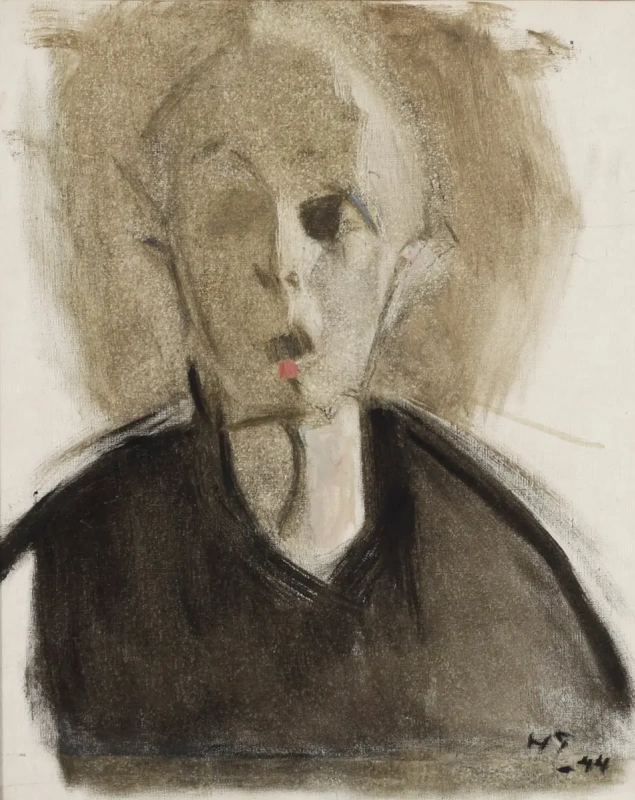

Helena Sofia Schjerfbeck

1880, 39×59.5 cm

At Sherfbeck’s right side of the canvas you can see tiny human figures, but it’s hard to say if they are coming or going. She is said to have depicted her own situation: a teacher and senior pupils went to Paris for an exhibition, leaving at home a young artist, who was too early to show her work in the French capital. But in the end, thanks to this painting, she received a grant from the Finnish Senate for a trip to Paris.

During her life in the British St. Ives, Schjerfbeck wrote her most famous work “Recovery” (1888). But the background of this painting, she did not want to tell, and the biographers had to work hard to dig it up. From family records it became clear that between 1883 and 1884 Helena was abandoned by his beloved. He wrote her an engagement letter, allegedly on the grounds that she was not strong enough to bear children. The artist destroyed the letter and asked her friends to burn all the correspondence, which mentioned this man. His name could not be restored, and Sheriffbeck herself never became a mother.

Helena Sofia Schjerfbeck

1888, 92×107 cm

The painting “Recovery” was the result of the mental experience of the artist. The little girl with torn hair leans forward in a wicker chair, half wrapped in a sheet. On the table in front of her, she holds a twig of young leaves in a blue and white circle. The painting’s theme is recovery, not despair. It is said that a six-year-old girl was an incredibly active child, and her teacher was happy to “provide” her Sheriffbeck for posing.

The canvas may seem traditional to the modern viewer, but at the first show in Finland, it was considered “too modern, underdeveloped and too French”. Not surprisingly, the French liked it: the work was awarded a bronze medal in Paris, and only then it was bought by Ateneum. Now it is one of the most popular exhibits in the museum.

In 1918, the artist painted Einar’s portrait “Sailor” – one of her best works in addition to self-portraits. She introduced us to a tanned young man with a naked torso, a sluggish head turn, a split chin and a light mustache. Artists often painted naked women, but not sensual portraits of men. This painting was exhibited in Finland only twice in 1918 – and never again during the life of Sherfbeck.

Helena Sherrfbeck, “Sailor” (1918). Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki.

Helen paid Einar a visit to a Norwegian sanatorium (the Finns at the time were literally obsessed with recovery in sanatoriums), and on the trip he got engaged to a young woman. Sherfbeck barely survived the news (she even wrote a will). Eventually they became friends again and she painted a second portrait, which is simply called “Einar Reuter”. The mustache and chin are in place, but her eyes don’t express anything – they’re just two dead circles of paint. “Sailor” is missing.

As Schjerfbeck grew older, she started to appreciate simplicity more and more. Some of her late still lifes are close to abstractions. In Still Life with Darkened Apples (1944), maturity is not yet the final, the fruit on the right is already black: there is the beauty of life and death, the unexpected brilliance. And it is not difficult to connect these paintings with late self-portraits that the artist painted while dying of cancer in a sanatorium. Simplicity is most extreme and touching in her last self-portrait, a coal sketch made in 1945. It is reminiscent of woodcarving: the face is presented schematically, as if carved out with a knife. The mouth is one line, the eyes are illegible: it’s the final, the last still life. Helen Schjerfbeck defies death, knowing that the work will survive it.