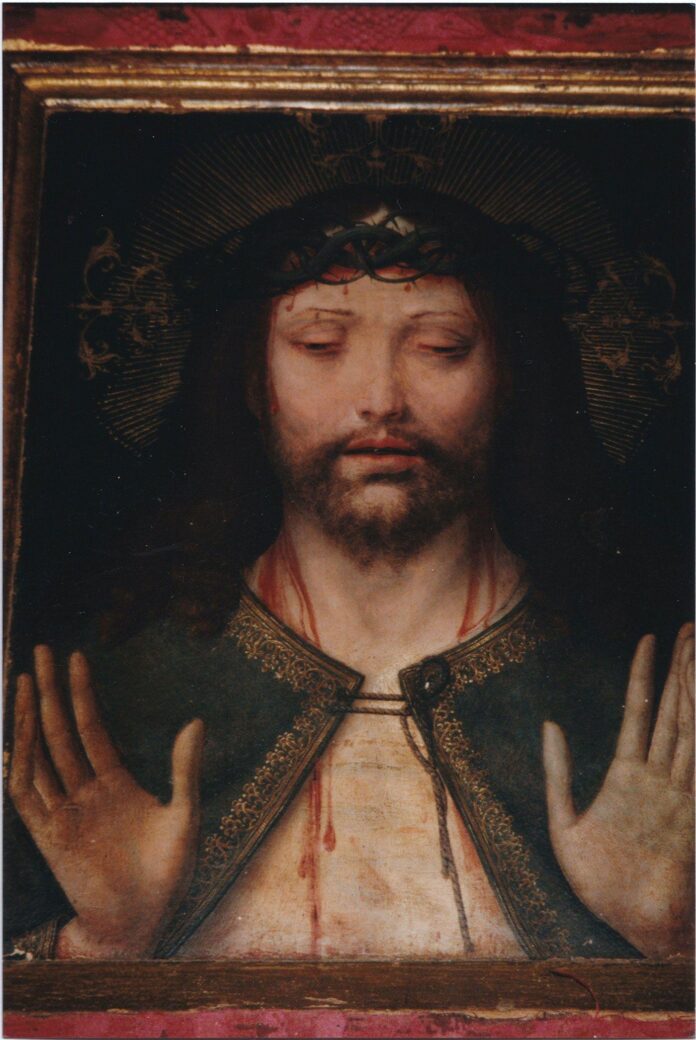

A beautiful European “Christ and the Crown of Thorns” of around 1500 was for centuries the Ethiopic emperors’ most revered emblem. It was taken by the British in 1868. Where is this painting, which is so much more than just a work of art, now?

In Ethiopic sources it is known as the “kwer’ata re’esu” (in Ge’ez: “the striking of His head”, St Mark XV, 19). Through the 17th and 18th centuries, it inspired numerous Ethiopic copies—manuscript illuminations, icons, church murals.

A debate has raged over the painting’s origins among art historians. It has been attributed to Quentin Matsys, Adriaen Ysenbrandt, Hans Memling and Bartolomé Bermejo. It may even have been painted in Ethiopia itself by Lazaro de Andrade, an artist with the Portuguese embassy of 1520-26 whose only identified work is a portrait in the Vatican collection of Lebna Dengel, the Ethiopian emperor at the time. If not de Andrade’s work, it can only have reached this mountaingirt outpost of Christianity through Portuguese connections from the period between 1520 and the expulsion of Jesuit missionaries in 1634, a time when Ethiopia forsook a habitual isolationism and entered into contracts with another Christian power.

This painting was carried into battle at the head of Yohannes I’s army in 1672, a practice continued during campaigns of following reigns against restive parts of the emperor’s domains or against Muslim regions on the fringes. In time it became the most revered item of the imperial regalia, and loyalty was sworn to the emperor in its name.

In 1744, it was lost in battle against a Sudanese Muslim tribe, then to be returned by ransom. James Bruce, one of the few Europeans to reach Ethiopia in nearly a century, wrote a few years later that Gondar was “drunk with joy” upon its return.

The last Ethiopic references occur early in the reign of Tewodros II (Theodore), which ended with suicide as British troops under General Robert Napier attacked his stronghold of Maqdala in 1868. Manuscripts and other treasure saved in the subsequent looting were auctioned a few days later. The largest purchaser, whose acquisitions comprise the bulk of the British Library’s Ethiopic collection to this day, was Richard Holmes, an archaeologist on secondment from the British Museum. Nowhere in the copious documentation of these events is there any reference to the painting.

In 1872 Yohannes IV tried to get the painting back to bolster his authority over his subjects, and wrote to Queen Victoria requesting its return. A search among the repositories of the Maqdala loot failed to unearth it, and Victoria later replied to her Ethiopian counterpart: “Of the picture we can find no trace and we do not think it can have been taken to England”. However, in 1890, a year after the death in battle of Yohannes IV, Holmes, who had been among the first civilians to enter Maqdala after its fall, discreetly revealed his possession of the painting to some art historians on the continent. He had resigned from the museum’s employ in 1870 to take up the post of Librarian at Windsor Castle, and with his known closeness to the Queen and her family he can scarcely have been ignorant of Yohannes IV’s request.

In 1905, an anonymous article on the painting appeared in the Burlington Magazine, illustrated by its only known photograph, and perhaps written by Holmes himself who was on the periodical’s consultative committee. While acknowledging the former ownership of Theodore, the article argues a Flemish origin. A revealing detail in the photograph, not commented on in the article, is a faint Ge’ez superscription in eighteenth-century lettering which reads: “How the head of our Lord was beaten”.

In 1917, Holmes’ widow sold the painting by auction through Christie’s. It reappeared on the art market in 1950, purchased by Luiz Reis Santos, an art historian from Coimbra who had known of its existence for some time and who had previously declared it to be a Portuguese work. Mindful of its Ethiopian links, he later offered it for sale to the Portuguese government to present to Haile Selassie during his State visit to Portugal in 1965. The offer was declined.

The painting appears to remain in Portugal, in the hands of a private collector unwilling to be identified. Aside from the interest within Ethiopia in its return, the possibility has surfaced of a royalist involvement, linking its restoration with that of the ancient Solomonic monarchy, which ended with the deposition of Haile Selassie in 1974.