Harry Belafonte, the legendary civil rights champion, singer and film star, has died aged 96.

Belafonte, whose memory is closely associated with the political and social activism of Martin Luther King, Jr, Paul Robeson, Langston Hughes and James Baldwin, ranked visual art and artists high as inspiration for his civil rights work and in the numerous creative collaborations he engaged in to help the cause of Black people and the disadvantaged in the United States and across the world.

The National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee, said in a statement “it joins the world in grieving the loss of a civil rights activist, cultural icon, and its 1999 Freedom Award honoree, Mr. Harry Belafonte”.

“From his early years of meteoric rise to celebrity in the 1950s,” the museum said, “he was connected to the American Civil Rights Movement and put his money where his mouth was by funding the efforts of organisations like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Student Nonviolent Co-ordinating Committee. He was part of the power-packed slate of Hollywood celebrities present during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom 60 years ago.”

In an interview with Forbes magazine in 2018, Belafonte elaborated on his belief that artists “have always been there” for social causes. “Go back to Charlie Chaplin, Paul Robeson, if you go back to a lot of art, not just in the performing arts, but certainly a lot of artists like Picasso and others who have always been deeply involved in social causes or social interests, from the point of view of activism, artists, from my experience, have always been there,” he said. “Much of what I have come to understand, as an activist, was learned from the artists who preceded me and who heavily influenced my beliefs.”

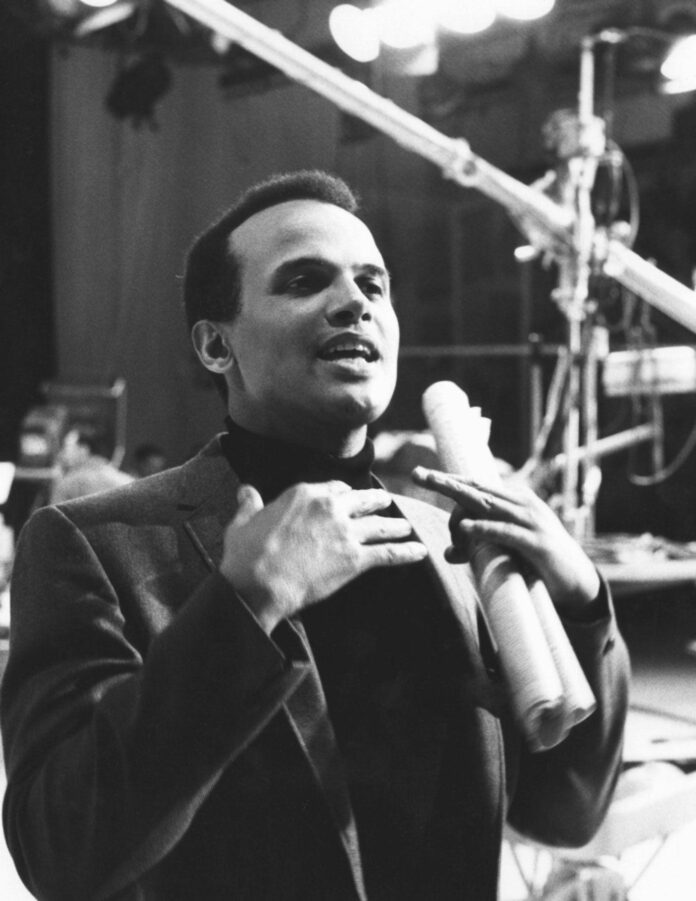

Carl van Vechten, portrait of Harry Belafonte, 18 February 1954 Library of Congress/Public Domain

His enormous success as a folk singer—with the 1953 single Matilda and then his album Calypso (1956), reportedly the first ever to sell a million copies—and as a screen actor, and his charismatic good looks, made him one of the most photographed people of his era, notably by Carl van Vachten. His friend and fellow folk singer and social activist Joan Baez painted a portrait of Belafonte in 2017, after more than 50 years of friendship. “He was the first singer I heard in folk music, before Pete Seeger and Odetta,” she wrote at the time. “I couldn’t know at that early age that we would end up marching with Dr. King.” Of the portrait, she added: “His was the easiest portrait I’ve ever painted. He’s so … handsome.”

Martin Luther King Jr, Joan Baez and Harry Belafonte, c 1965-66 Bob Fitch photography archive, © Stanford University Libraries

Belafonte’s success also gave him the resources and the profile to make a profound contribution to the Civil Rights movement, notably after meeting King in 1956, becoming one of his main supporters, offering King a home away from home in his New York apartment and bailing him out of prison on occasion. Belafonte supported King’s widow Coretta Scott King and her children financially and personally following King’s assassination in 1968.

The Kings’ youngest daughter, the lawyer and minister Bernice King, recalled, “When I was a child, Harry Belafonte showed up for my family in very compassionate ways.” She posted an image of Belafonte supporting Coretta Scott King at her husband’s funeral, writing: “Here he is mourning with my mother at the funeral service for my father at Morehouse College. I won’t forget…Rest well, sir.”

The visual artist that Belafonte is most closely associated with is the Chicago-born draftsman Charles White. They first met in 1947 at a meeting of the Committee for the Negro in the Arts. At the time of a 2018 retrospective of White’s work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Belafonte recalled the day: “I had just come out of the war and uh, I had no identity. I walked into a place that just blew me away. A lot of Black people gathered in a room making noise and talking and looking like they had purpose in life … The purpose was to advance black culture. It was to become major participants in the American cultural scene. We could convene and debate and get a grasp on what the collective power of Black art could do. It was the centre of rebellious thought, glorious thought, and the leaders of that were people like Charlie White and Langston Hughes and James Baldwin.”

Belafonte became a collector of White’s work, and then in 1957 when Belafonte, by then a huge pop star, was offered an hour of primetime television to host, he commissioned White to make an image—Folksinger (Voice of Jericho: Portrait of Harry Belafonte) 1957—for use on the show.

As Belafonte recounted 60 years later: “I couldn’t find enough ways in which to let the world be exposed to Charlie. I was so caught up in his work. I said in this special not only will they hear the beauty of the songs but the audience would have a visual experience—not just a set—but something that was filled with passion. It shook up television because they never quite saw anything like that, all this blackness. It was incredible.”

Born in New York City, to a father born in Martinique and a mother born in Jamaica, Belafonte grew up in Harlem but spent 1936 to 1940 in his mother’s native island before being reunited with the rest of his family in New York. After serving in the US Navy he took up acting in New York and his growing celebrity as singer and actor meant he was a natural choice for the gala that Frank Sinatra planned for the inauguration of President John F Kennedy in 1961.

The actor Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte at the National Monument, Washington DC at the conclusion of the March on Washington, 1963

In 1963, Belafonte rallied his Hollywood colleagues, including Charlton Heston, Marlon Brando, James Garner and his friend Sidney Poitier to attend the conclusion of the March on Washington, when King gave his immortal “I have a dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial. The following year, James Baldwin reflected in The Uses of the Blues (1964) of how little had changed: “The fact that Harry Belafonte makes as much money as, let’s say, Frank Sinatra, doesn’t really mean anything in this context. Frank can still get a house anywhere, and Harry can’t. People go to see Harry and stand in long lines to watch him. They love him onstage, or at a cocktail party, but they don’t want him to marry their daughters. This has nothing to do with Harry; this has everything to do with America.”

Belafonte’s memoir My Song: A Memoir of Art, Race, and Defiance (2012) is a vivd, beautifully written account of a packed, consequential life. After the March on Washington and the publication of Baldwin’s The Uses of the Blues, he still had another six decades of campaigning ahead of him, most recently in urging people to vote in the 2016 and 2020 US presidential elections.

In the 1980s he supported the cultural boycott of South Africa and was part of efforts to combat starvation in Africa, taking part in the 1985 Live Aid concert in London and the recording of the all-star fund-raising single We Are the World. In 2013, talking of the record and preparing for its 30th anniversary, he returned to the theme of the artist’s role in society. “People who represent art have the public trust,” he said. “I think we are trusted by people who listen to our songs and look at our paintings. And that’s a huge gift. To think that artists can do best is to focus a spotlight on any given subject … and more often than not the public will respond.”

- Harold George Bellanfanti (Belafonte); born New York City 1 March 1927; married 1948 Marguerite Byrd (marriage dissolved 1957); 1957 Julie Robinson (marriage dissolved 2004), 2008 Pamela Frank; National Medal of Arts 1994; died New York City 25 April 2023