The International Criminal Court (ICC) has issued an international arrest warrant for President Vladimir Putin. The court wants the Russian leader to stand trial for war crimes. But, if Putin is ever to be held account for the intent of his actions during the war in Ukraine, then the ICC’s prosecuting case will have to rely on evidence taken from the ground in Ukraine.

A new briefing report prepared for the European Union Advisory Mission by the NGO Blue Shield International (BSI), has tentatively made the claim that the Putin regime has premeditatively, systematically—and provably— targeted heritage sites in Ukraine. If the report is correct, the critical legal threshold needed to prosecute Putin for a war crime is now significantly closer.

The report has capitalised on what appears to be a turning tide in the 19-month long war. As the Russian frontline retreats, Blue Shield operatives have, often for the first time, been able to visit, in person, eight damaged sites that have only previously been monitored via satellite footage and social media posts. Instead of relying on digital material, they have been able to acquire first-hand witness testimony. Their findings have been shared with The Art Newspaper exclusively.

In April 2022, two months into the war, The Art Newspaper made an assessment. The Western media, at the time, played host to widespread claims that Russia was targeting Ukrainian heritage sites and places of collective identity in a campaign of cultural cleansing. This publication assessed that the available evidence, at that juncture, was not comprehensive enough to demonstrate beyond doubt that a coordinated cultural cleansing operation was indeed taking place. The damage was criminally indiscriminate, but it could not be proved that it was targeted and intentional.

That assessment has now changed. Between November 2022 and August 2023, Blue Shield personnel were able to visit a sample of damaged sites across territory now controlled by the Ukrainian government. They have found what, they argue, is limited but strongly indicative evidence of deliberate targeting in at least two cases, and of looting, potentially linked to the manipulation of cultural identity, in two others. Two religious sites close to the Belarus border were deemed too dangerous to visit. Some sites have been well reported; others not. The sites cannot yet be individually identified in order to protect local eye-witnesses should the war shift once more in Russia’s favour.

The briefing, titled Assessment of Damage/Destruction of Cultural Heritage Sites in Ukraine, November 22- August 23, is a feasibility study: an assessment of the practicality of a proposed plan. In this case, it is designed to look at material damage in relation to potential violations of international humanitarian law as it relates to cultural property law enshrined in the 1954 Hague Convention.

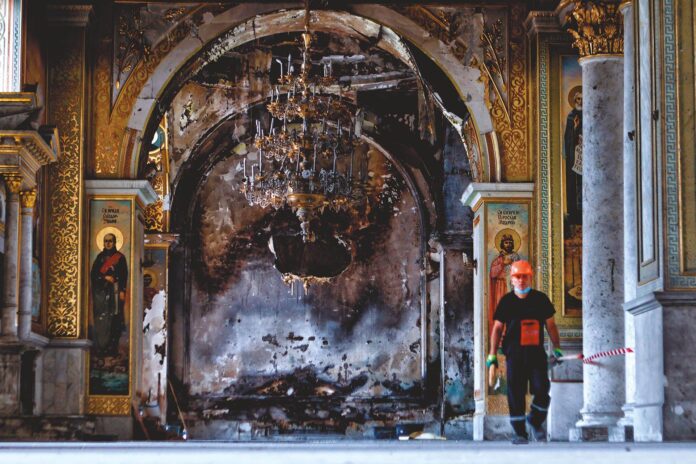

Appalling events like the deadly airstrike on the Mariupol Theatre in March 2022 may be a war crime—but it has been not considered under the heritage rubric because the theatre, a reconstruction from 1960, is unlikely to qualify as a heritage site under the Hague Convention. (Odesa’s Transfiguration Cathedral,severely damaged by a missile in July of this year, is a legally off-limits place of worship, so outside the parameters of the recent World Heritage List so it isunlikely to qualify as a heritage crime.)

The Transfiguration Cathedralwas added to the World Heritage List by Unesco in January, but was damaged last month by a Russian missile which broke through the roof

© Yan Dobronosov/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images

Collateral, or Intentional?

Blue Shield assess that “the majority of damage to and destruction of cultural property in the oblasts [regions] visited has been collateral,” the report states.

“However, visiting sites identified through satellite imagery, evidence has been found on the ground at several sites where violations have potentially taken place,” it says. “There are at least two instances where there is evidence that sites have been specifically and intentionally targeted.”

Claims of targeting at these sites were made at the time of the strikes—but they were not evidenced. Now, Blue Shield has been able to combine on-the-ground evidence gathering with all available digital imagery.

One of the cultural institutions cited is an important art and local history museum in the Kyiv oblast. It is strongly linked to Ukrainian identity and was located in an area formerly occupied by Russian troops, who used it as a staging site. The museum was burned out but the nearby village and adjacent houses remained undamaged.

Eye-witness testimony collected by Blue Shield states the museum was destroyed by a single rocket or artillery strike in February 2022. It remains unclear whether Ukrainian secret police or uniformed officers were able to collect forensics, including ballistic fragments.

The second institution is a literary museum in a historic house. It was partially destroyed in March 2022 during the Battle of Kharkiv with a single missile strike, launched from the south, which hit its roof. The museum is dedicated to a figure closely linked to Ukrainian self-identity. There was no fighting anywhere nearby. Here, the gathering of evidence has been hampered by the rapidity of repairs to the building but also, as witnessed by museum staff, by the removal of ballistic fragments by unknown parties.

Whether a third impacted site was targeted —another local history museum in the then Russian-occupied Kharkiv region—is uncertain. According to the report, there is evidence of small arms fire and a potential mortar impact adjacent to the building that damaged it, but the assessment visit was probably too long after the fact for accurate verification. Extensive damage to other nearby heritage sites makes it hard to demonstrate a deliberate singling out rather than incidental damage.

The report also details witness testimony of two well-established incidents of looting in the Kherson region, where thousands of artworks and other holdings were removed by uniformed personnel in military vehicles under the direction of the Russian secret services, and according to eye-witnesses, with the assistance of academics from Moscow and occupied Crimea.

Blue Shield also visited Kyiv, Odesa, Chernihiv, Kherson, Kharkiv and Donetsk oblasts to assess the current activities of the Ukrainian heritage community and armed forces when it comes to gathering evidence. This included a fourth potential incident of deliberate targeting – a local history museum in the east of Ukraine which was possibly struck by a Russian S-300 missile. There were no military objectives nearby.

Despite the report’s relatively confident assessments, it states that not enough is being down to investigate and secure the evidence needed to buttress the extensive claims that Putin is targeting cultural sites. Blue Shield’s small sample is the first systemic analysis of its kind. “No [country] has done enough,” Blue Shield’s president, Professor Peter Stone, said. “Even in these two cases, there may not be enough evidence to stand up in an international court.” Evidence, says Stone, preferably needs to be gathered during the week following an incident. This is often impossible in a war zone.

This report can act as a template. The expansion of Blue Shield’s sample study to a comprehensive survey of forensic and witness evidence would begin to establish intent as well as responsibility—only then can justice be done, and those responsible be held to account.

• Robert Bevan is an author and member of Blue Shield UK and ICOMOS-ICORP