The busiest week of London’s art world calendar is almost upon us. As everyone gears up to take on Frieze’s big white tents and a buffet of blockbuster museum shows, they may wonder when they’ll ever be able to have a break. The insider tip is to visit All Saints Chapel, an oasis of calm just off Oxford Street that boasts magnificent decorative features, including a sweeping crucifixon fresco and stained glass windows by the Victorian artist John Richard Clayton.

This unique 19th-century space is being used to stage the intimate exhibition, “Living Memory,” which presents sculptures by Louise Bourgeois and paintings by Israeli artist Gideon Rubin against a soothing soundscape by French musician Nicolas Godin. The show explores how each artist has been informed by memory, and foregrounds their ability to morph materials into strangely familiar, human forms.

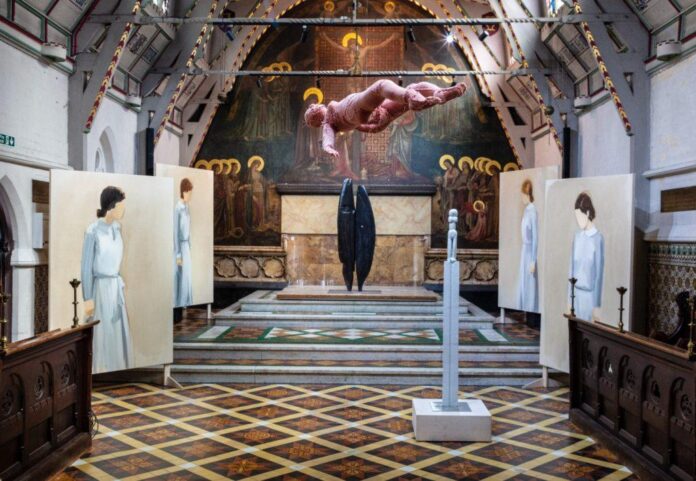

Installation view of “Living Memory” at All Saints Chapel in London. Photo: Richard Ivey.

Adapted for all-women convent, Clayton’s crucifixion scene is unusual for only depicting women attendants. These dutiful figures are explicitly echoed in new paintings by Rubin, which were modeled on stills from the German film (1931) by female director Leontine Sagan. Almost life-size, they have a commanding presence, but without faces and dressed in plain white dresses they never overwhelm their ornate surroundings.

“Gideon has always used found photographs from flea markets that are completely anonymous to him, and he’d reimagine their lives,” said the show’s curator Beth Greenacre. “Its very much about time passing and the loss of detail.”

Stealing the show, inevitably, are the three sculptures by Bourgeois, two of which belong to her “Personages” series from the 1940s. These tall abstracted forms are a masterclass in how little detail is needed for a composition to be richly suggestive. (1949), which takes centre-stage in place of an altar, consists of two curved slabs of woods that merely brush against each other but instantly communicate familial affection.

“She had just left Paris and was an emigré in New York,” said Greenacre. “She talked about these as memories of the families and friends she’d left behind. They’re totems of characters and they become what we want them to be as well.”

Installation view of “Living Memory” at All Saints Chapel in London. Photo: Richard Ivey.

As in Rubin’s work, much can be read into a single gesture, post or tilt of the head. “In that space between abstraction and figuration, what is possible?” said Greenacre. “Its interesting to think of Bourgeois’ history of psychoanalysis and how she uses her art as a way of releasing challenging moments from her past.”

Leaping forward many decades to Bourgeois’ later life, (2000) is a splayed naked body, somehow simultaneously limp and taut, and roughly stitched together with scraps of unnaturally pink fabric. Suspended from the ceiling, the small doll slowly spins on its see-through string. The work is inspired by the idea of the “hysterical” (presumed female) patient confined and studied by the male neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, about whom Bourgeois felt both critical and curious.

Though in some sense, references like these might feel out of place in a chapel, the space’s unique capacity for peaceful contemplation feels entirely appropriate for artworks that, much like the religious art that came before them, speak to universal themes of remembrance, loss, spirituality, and transformation.

More Trending Stories: