The US Copyright Office has received applications to register a wide variety of arguably creative objects for copyright protection in recent years, including driftwood that has been shaped and smoothed by the ocean, a photograph taken by a monkey, a mural painted by an elephant and the look of natural stone for its cut marks, defects and other qualities. In every instance, its response has been the same: no. The Copyright Office Compendium, its guide to policies and procedures, explicitly states that works created by nature, animals or plants cannot be registered. That also includes “works produced by a machine or mere mechanical process that operates randomly or automatically without any creative input or intervention from a human author”.

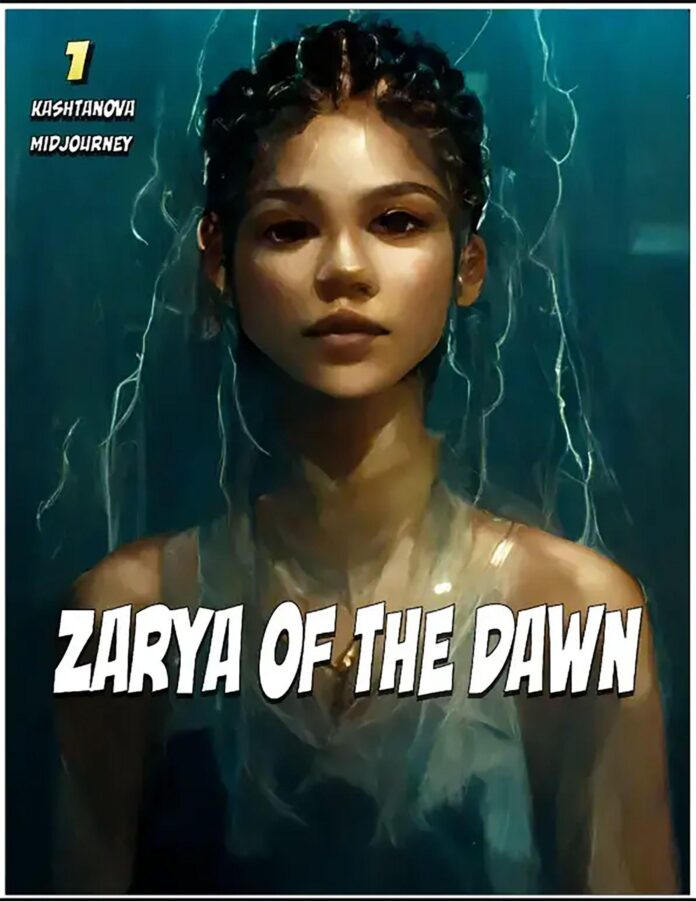

Some wiggle room may be added to this realm, the result of the new guidelines issued by the Copyright Office and a recent decision regarding the copyright registration of a comic book, Zarya of the Dawn, authored by New York-based artist and artificial intelligence (AI) consultant Kris Kashtanova with images generated through the AI platform Midjourney. The Copyright Office granted copyright to the book as a whole but not to the individual images in the book, claiming that these images were not sufficiently produced by the artist.

Perhaps recognising that there is a growing number of images created by humans and modified by way of AI or generated by AI and modified by human activity, and that Zarya will not be the last of its kind, the Copyright Office in March offered additional clarification of its “human authorship requirement”, some of which describes a path forward for artists in this new realm. In this new clarification, the Copyright Office asserted that when “a work’s traditional elements of authorship were produced by a machine, the work lacks human authorship and the Office will not register it”. However, there may be instances in which “a work containing AI-generated material will also contain sufficient human authorship to support a copyright claim. For example, a human may select or arrange AI-generated material in a sufficiently creative way that ‘the resulting work as a whole constitutes an original work of authorship’.”

The Copyright Office likened some uses of artificial intelligence to more traditional mechanical tools, such as a visual artist’s use of Photoshop or a musician creating different sounds through a guitar pedal, which would be permitted for those seeking copyright registration: “[W]hat matters is the extent to which the human had creative control over the work’s expression and ‘actually formed’ the traditional elements of authorship.”

A partial and temporary solution

Only human authors or artists should be named on applications for registration, with any artificial intelligence technologies noted in “a general statement that a work contains AI-generated material. The Office will contact the applicant when the claim is reviewed and determine how to proceed.” In other words, decisions will be on a case-by-case basis.

The process of publicising policies with regard to the use of AI in the arts is, to a degree, a work in progress, and the Copyright Office has plans for “public listening sessions” throughout 2023 in order to obtain more information about technologies and their impact.

Van Lindberg, an intellectual property lawyer based in San Antonio, Texas, who represented Kashtanova before the Copyright Office, says that “thousands of AI-assisted works are being generated every day” and that new guidance for how it will treat this type of artwork promulgated by the Office “is a step towards accepting it. I am glad that the Office has indicated that they are willing to evaluate AI-assisted works for registration.”

Even though the expanded guidelines do not go as far as Kashtanova would have liked, “there is a lot in this guidance that I agree with”, Van Lindberg says. “The Copyright Office is correct that copyright requires human authorship, and the human-provided creative elements are what lead to protectability.” He adds that “non-human authorship is still a barrier and will be until that is changed by the Supreme Court or Congress”.

Where humans end and machine-learning begins is a difficult line to draw. Scott Hervey, an intellectual property lawyer and partner in the California-based Weintraub Law Group, says that “a human may select or arrange AI-generated material in a sufficiently creative way that the resulting work as a whole constitutes an original work of authorship. Or, an artist may modify material originally generated by AI technology to such a degree that the modifications meet the standard for copyright protection. In these cases, copyright will only protect the human-authored aspects of the work, which are independent of and do not affect the copyright status of the AI-generated material itself.”

These scenarios acknowledge that AI is a tool to be used, but it also is intended to create outcomes independent of humans. “If humans can control the end product”, he says, “is it really AI?”

Another complex copyright issue involves AI platforms that are fed existing copyrighted images, which users of this technology are able to alter to produce derivative images that may be put up for sale. Getty Images and a number of artists have filed lawsuits against some of these platforms—Stable Diffusion, Midjourney and Deviant Art—for copyright infringement. Those cases have yet to be heard in court. James Lorin Silverberg, an intellectual property lawyer in Washington, DC, says the Copyright Office is looking into whether or not modifications should be made to the federal copyright law with regard to the relationship of the original copyrighted material and AI-generated images based on it. “It is possible that an AI work does not present the underlying work’s copyrightable content at all, but merely learned from it,” he says.