In the early 1960s, Lee Mullican, the San Franciscan artist best known for his modernist abstractions, swapped his paintbrush for the painter’s ink knife. Using its thin edge, he would apply paint to his canvases, building color in finely textured lines he called “striations” that lent his cosmic compositions a rhythmic quality. It’s a technique he would deploy for the rest of his career—except for a brief time in the spring of 1987, when Mullican would trade his knife for a computer program.

During his three-decade tenure as a faculty member at the UCLA School of the Arts and Architecture, Mullican participated in the university’s Program for Technology in the Arts, which granted him access to an IBM 5170 loaded with a Truevision Advanced Raster Graphics Adapter and linked to a stylus.

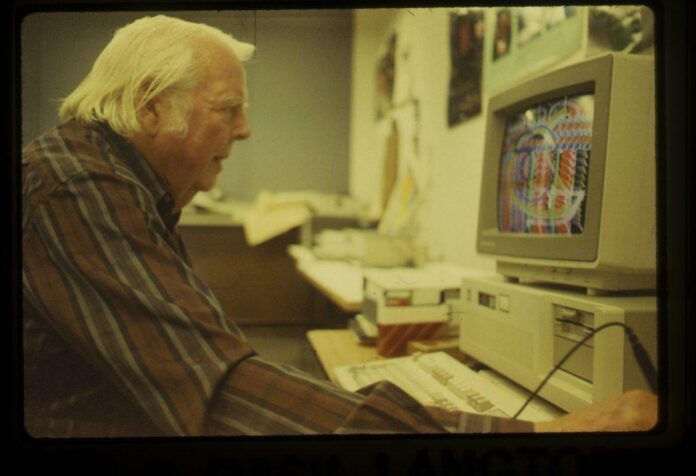

With the machine, the then 67-year-old began experimenting with digital pattern-making, generating more than 300 16-bit landscapes of otherworldly striations in vibrant neons. To document his process, he took photographs of the screen as he worked.

“I found that beyond what one thought, the computer as being hard-lined, analytical, and predictable,” he reflected, “it was indeed a medium fueled with the automatic, enabled by chance and accident, the discovery of new ways of making imagery.”

Lee Mullican at the computer (1987). Photo: Basil Langton, courtesy of the Estate of Lee Mullican and Feral File.

On March 23, a group of Mullican’s computer artworks is resurfacing by way of an NFT drop by Feral File. The collection, titled “LeeMullican.PCX,” encompasses 12 of the painter’s digital experiments, with each purchase bundling the original .PCX file (the Picture Exchange image format), an enhanced 35mm slide scan, and collector rights.

Minted on Tezos, the series will first be sold through 20 sets featuring an edition of all 12 artworks for $2,400, before the remaining sets are sold as individual editions, priced at $200 each.

Lee Mullican, (1987). Photo courtesy of the Estate of Lee Mullican and Feral File.

The release has been curated by Anika Meier, the curator and writer who organized Marina Abramović’s NFT debut, and Cole Root, the director of the Estate of Lee Mullican. For both, the artist’s work with computers is in line with his conviction, as one of the pioneers of the heady Dynaton movement in the 1950s, that art should be liberated and liberating.

“Lee’s digital works demonstrate relentless experimentation,” Root told Artnet News. “He wasn’t running away from new tools and technology of the day. He embraced them and shared what he learned with his students.”

Lee Mullican, (1987). Photo courtesy of the Estate of Lee Mullican and Feral File.

“Mullican came from painting,” Meier added. “He used his knowledge of painterly techniques as a guide when he began working with computers and found common ground between his own style of painting and the chance made possible by the computer.”

Chance and automatism are indeed bound up with Mullican’s practice, which folded in influences as varied as topography, mysticism, ancient philosophies, and Surrealism. His works in the late 1940s led the Bay Area’s short-lived Dynaton movement, the meditative canvases of which, created by the likes of Gordon Onslow Ford and Wolfgang Paalen, stood in contrast to the action-driven Abstract Expressionism on the East coast.

Lee Mullican, (1948). Courtesy Marianne Boesky Gallery.

Mullican’s digital pieces are as meditative as any of his physical canvases, their creation similarly relying on chance and possibility. As the artist recalled in the 2008 documentary Finding Lee Mullican, “You can wipe out something [on the computer] in one minute and then have it back in a different way. It was truly a creative experience for me.”

“LeeMullican.PCX” is not the first time that Mullican’s computer art has come to the NFT market. In November 2021, Web3 platform Verisart, in partnership with Marc Selwyn Fine Art and Mullican’s estate, released 15 of his digital works as NFTs in a sale titled “Computer Joy,” which yielded 35 ETH (about $62,675).

In intention, this latest release also joins a run of other NFT projects similarly minting early computer artworks, including Herbert W. Franke’s Math Art drop on Quantum Art in May 2022 (also overseen by Meier), and Sotheby’s “Natively Digital 1.3” sale in 2022 which featured pieces by Vera Molnár, Charles Csuri, and Roman Verostko. The aim isn’t just to situate contemporary digital art within the lineage of computer art, but to fold these trailblazers into the blockchain age.

Lee Mullican, (1987). Photo courtesy of the Estate of Lee Mullican and Feral File.

Further, Meier is quick to put to rest any criticisms that these pioneering works are being “used to legitimize NFTs as art.” In her view, “it’s more the other way around: NFTs bring attention to the beginnings and history of digital art. Many of the pioneers are finally getting the recognition they deserve for their achievements, their fighting spirit and spirit of discovery, and their perseverance.”

And all the more so for Mullican’s digital experiments, which, as Root put it, the artist embarked on “not for anyone else or a market.” That they are now finding an appreciative audience is a credit to the art itself, if not Mullican’s spirit of freeform exploration.

“I think a significant takeaway from this work is that Lee was making it for his own satisfaction and enjoyment. That’s why the work holds up, because it comes from a pure place of joy and creativity,” Root added. “He was having fun and it shows.”