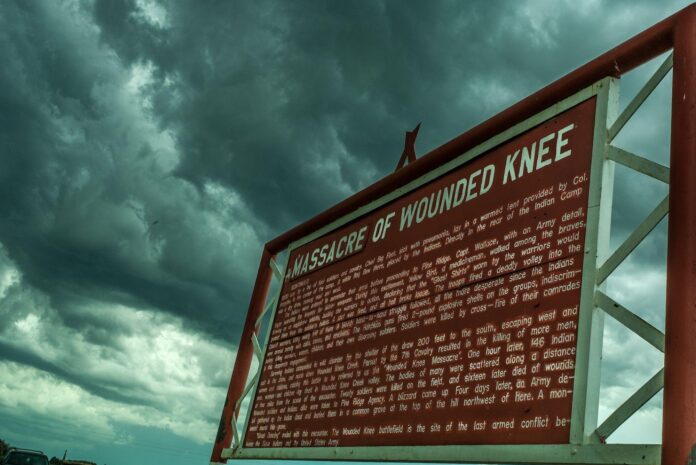

Last November the Founders Museum, a small institution housed in a library in Barre, Massachusetts, repatriated 150 ill-gotten artefacts to the Laktoa and Sioux nations of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, the site of one of the deadliest massacres initiated by the US military against the Indigenous Americans.

Many of the items in question—ranging from ritual clothing to moccasins—were believed to have been plucked from the battlefield in the wake of the carnage in 1890. Their return marked an important coda to a century-long struggle for members of the nations affected by that massacre, in which around 300 Lakota are believed to have been killed. But it also raised complicated questions about the next step in the recovery process: what happens after the artefacts go home?

There isn’t yet consensus regarding the ultimate fate of the objects returned by the Founders Museum, according to a recent report by The New York Times. Some tribe members want to bury or burn the funerary items in accordance with religious practices, while others would like to see them displayed in museums run by tribal councils. Still others believe that the objects should be returned to the descendants of those who originally owned them.

“It’s the tribe’s prerogative however they wish to utilise or reinvigorate the item,” Shannon O’Loughlin, the chief executive for the Association on American Indian Afairs and a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, told the Times.

Last year it was reveal that less than half of the institutions subject to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (NAGPRA)—which requires government-funded institutions to acknowledge their ownership of Native human remains and sacred objects—had returned those items to the groups to which they belong. In October 2022, the Department of the Interior proposed to overhaul regulations to speed up implementation of the act and repatriation of sacred cultural and burial objects, as well as human remains.

The Founders Museum did not repatriate objects in its collection for decades, claiming it was not covered by NAGPRA because it didn’t receive federal funding. Last November’s repatriation occurred more 130 years after the Wounded Knee Massacre and a decade after an agreement was reached between the tribes and institution.

Marlis Afraid of Hawk, whose grandfather survived the massacre, told the Times she supported burning the artefacts. “When your relative died, you burn their belongings”, she said.

Ivan Looking Horse, whose ancestors were killed at Wounded Knee, advocated for a more varied approach. “Some things are for burning, some are for burying and some things are for educating,” he told the Times. “Others can be used for praying with generations to come”.

For now, the objects are being housed at Oglala Lakota College in Kyle, South Dakota, where a caretaker will continue to pray over them daily.