It’s been 200 years since French artist Rosa Bonheur was born and people are still talking about what she was wearing when she painted live lions and tigers and cows.

Bonheur was one of a handful of mid-19th century women issued a police permit allowing them to wear men’s clothes. Yes, it’s true: the accomplished Bonheur—who audaciously used the monumental scale typically reserved for history painting to depict livestock, and was likely the most commercially successful woman artist of her time—wore pants.

But fascination with Bonheur’s persona has detracted from a closer look at her work, which portrayed animals with psychological presence and meticulous anatomical detail.

“There are so many things to [uncover] about Rosa Bonheur, because we study her more for her unconventional life than for her art,” said Lou Brault, assistant director of the Château de Rosa Bonheur, a museum opened in 2017 in the artist’s longtime house in the town of Thomery. To some, Bonheur is a model for women’s liberation because she never married (deciding instead to spend her life with another woman), was childless, and supported herself financially. “There are not so many studies about what she’s fighting for through her art.”

Rosa Bonheur, Deux Lapins (1840). © Mairie de Bordeaux, musée des Beaux-Arts, photo: F.Deval.

In honor of the bicentenary of her birth this year, a retrospective of some 200 paintings, graphic works, sculptures, and photographs reintroduces Bonheur’s work to French audiences and offers new ways to look at the artist. The show recently debuted at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux, where it broke attendance records, and opens at the Musée d’Orsay later this month.

Exhibitions about Bonheur’s lost artworks and photography (a barely researched aspect of the artist’s work, even though she left behind her darkroom and thousands of exposures) have opened concurrently at the Château de Rosa Bonheur. Bonheur’s last show in Paris was a full century ago, and there has never been an exhibition of this scale devoted to her work in France.

“We were shocked by how important she was in the 19th century,” said Brault. “Here in France, in the 21st century, nobody knows her anymore.”

There are a few reasons why, including the fact that Bonheur’s chosen genre, animal painting, wasn’t highly regarded in France. “Being a woman artist and painting animals were two ‘mistakes,’” explained Leïla Jarbouai, chief curator at the Musée d’Orsay. “She made popular art, and her art was duplicated in prints, another mistake. And she sold most of her works abroad, in the United Kingdom and in the United States, so French visitors could not see her accomplished work.”

Rosa Bonheur, Têtes et encolures de bœuf brun. Château de Rosa Bonheur. Photo © musée d’Orsay /Alexis Brandt.

Bonheur has always been more famous abroad than at home, even modeled into a popular doll for young American admirers in the 19th century.

Bonheur’s ‘mistakes’ may have turned French art lovers off from the major canvas she did leave in her native country, such as Ploughing in the Nivernais (1849), of oxen trudging through rich dirt, but some novelties on view at the retrospective may pique their interest.

The painting reproduced on the publicity poster for the Musée d’Orsay exhibition, The King of the Forest (1817), is of a regal stag staring piercingly at the viewer and it has never been shown in France, not even during Bonheur’s lifetime. Some recent discoveries excavated from storage at the Château de Rosa Bonheur, also never exhibited, are being debuted, including a grand preparatory sketch for her famous painting The Horse Fair (1852-55), and a cyanotype of a horse. The exhibition also includes personal things that Bonheur never meant to show, like painted pebbles and caricatures.

Jarbouai believes that the crowds that visited Bonheur’s retrospective in Bordeaux, and the growing curiosity about her in general, are linked to a greater interest in women artists today. There has also been a concerted effort since 2017 to revive Bonheur’s legacy in the place where she lived and worked for the last four decades of her life.

Rosa Bonheur, Cheval de face avec son palefrenier (ca. 1892). Château de Rosa Bonheur. Photo © musée d’Orsay /Sophie Crépy.

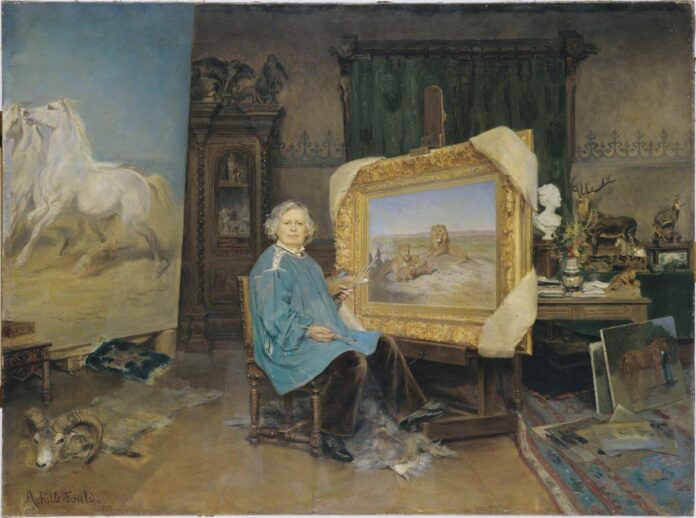

Bonheur bought the Château de By near Fontainebleau with earnings from selling her monumental The Horse Fair, which was shown at the Paris Salon and ultimately donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art by Cornelius Vanderbilt. In By she lived among a menagerie of creatures including monkeys, tigers, and lions (the skin of Bonheur’s pet lioness, Fathma, ultimately became a rug strewn near her easel). Bonheur bequeathed the château to her companion, American painter Anna Klumpke, who in turn left it to her niece. Until 2017, the house and all its untouched contents were passed down within the same family, who they claimed that they tried to sell it to the French government but that there was no interest.

“People didn’t care about her. She was just, like, painting cows,” said Brault, whose mother bought the château in 2017 in order to convert it into a museum. After securing funds to open it up to visitors year-round, the Château de Rosa Bonheur started inventorying her archives to encourage research.

“This place needs to be here to make people talk about Rosa Bonheur,” said Brault. “There was a Rosa Bonheur street, there was a famous café in Paris named Rosa Bonheur. Rosa Bonheur was a name people already knew but they didn’t know who she was. What we hope is that the bicentenary and the exhibition change this, and that afterwards people know she was a very famous artist of the 19th century and she painted animals.”

More Trending Stories:

Has the Figuration Bubble Burst? Abstract Painting Dominates the Booths at Frieze London

Jameson Green Won’t Apologize for His Confrontational Paintings. Collectors Love Him for It

Auctions Live Now: