By the end of Brian Piper’s research trip to the rare book library at Emory University, he had already seen much of its historic photo collection. But then a file landed at his table, containing a striking full-length portrait of a gentleman in hunting attire complete with dogs, a shotgun and a bundle of dead birds. The gelatin silver print was produced by Washington, DC-based photographer Addison Scurlock—who famously captured sitters including W.E.B. Du Bois, Marian Anderson and Martin Luther King Jr.—and yet Piper, who specialises in African American studio photography, had never seen a Scurlock image quite like this.

“Scurlock was known to be a bit of an autocrat in the studio. This [sitter] either had enough influence or was willing to pay to let him insert that much of his creative vision into how he saw himself,” says Piper, co-curator of upcoming exhibition Called to the Camera: Black American Studio Photographers at the New Orleans Museum of Art (16 September 2022-8 January 2023). “It’s done in that classic Scurlock, heavily polished style. I had to walk away from the table, it’s really, really great.”

Arthur P. Bedou, Sisters of the Holy Family, Classroom Portrait, 1922 XULA University Archives and Special Collections. Image Courtesy of Xavier University of Louisiana, Archives & Special Collections © Arthur P. Bedou

This regal likeness of an anonymous man will be on view in Called to the Camera and encapsulates the show’s goal to illustrate the self-representation of Black individuals and communities, through the lens of Black professional photographers, from the earliest day of the medium. Like this hunting portrait, many of the over 170 vintage prints in the exhibition are drawn from archives and history museums and rarely shown in art museums. “The photographs do belong in historical archives,” Piper says. “But, if we are doing our job properly as historians of photography in an art museum, we need to be showing them here, too.”

This show is the first to focus on Black American studio photographers from the 19th century onward, demonstrating their activity from the camera’s introduction to the US (which preceded the end of slavery by over 20 years). “You would think that we would be past the moment where a show like this is groundbreaking, but we’re not,” says co-curator Russell Lord.

James Presley Ball, Alexander S. Thomas, late 1850s Cincinnati Art Museum, Gift of James M Marrs

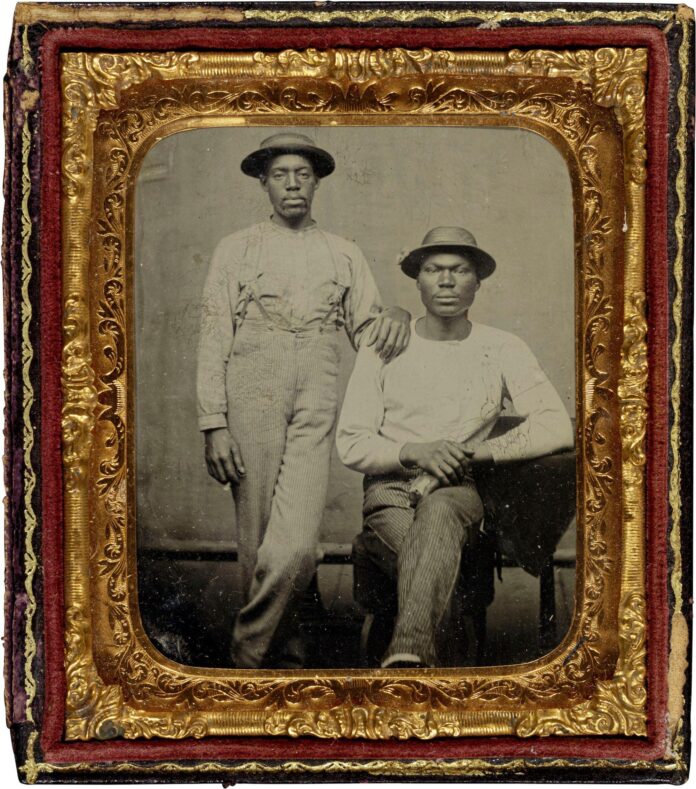

Photographers such as Augustus Washington, James Presley Ball, James C. Farley and The Brothers Goodridge started working soon after daguerreotypes came to America in 1839, with most of this first generation of professional photographers active in the North or Midwest. On the sitters’ side, portraits were a means of asserting personhood. Growing evidence shows that enslaved people both openly and secretly sought out photographic likenesses of themselves across the American South.

Over three dozen photographers from across the United States are included in the exhibition, some nationally known and others active regionally like Robert and Henry Hooks in Memphis, and Morgan and Marvin Smith in New York. A rare example of a woman-owned studio is that of Florestine Perrault Collins, whose shop was prominent in early 20th century New Orleans. The survey spans a range of formats, from daguerreotypes to panoramic photographs, tintypes and hand-painted gelatin silver prints.

Florestine Perrault Collins, Portrait of a young woman dressed in white, 1920-1928 The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2001

There are multiple formats of portraits of abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who is considered the most photographed American of the 19th century and sat for four Black photographers in his lifetime.

Other, lesser-known images are being exhibited for the first time, such as original prints from the Hooks Brothers Studio in Memphis—established in 1907 and among the oldest continuously operated Black-owned businesses in that city.

Hooks Brothers Studio (Robert and Henry Hooks), Al Green in the Hooks Brothers Studio, around 1968 Collection of Andrea and Rodney Herenton.

The Hooks Brothers Photograph Collection, consisting of original photographs, negatives, equipment, and ephemera was acquired by the RWS Company, LLC in 2018.

“The vision for the show is adjusting the historical narrative of photography by putting this work in our understanding of what makes ‘art’ photography today, in part because [studio portraiture] was a prominent way that Black Americans were participating in photography,” says Piper.

“Marginalized histories and marginalized objects go hand in hand, because if you don’t expand the types of photographs that you show in an art museum then you won’t be able to include all of those histories,” Lord says. “You hear the term ‘democracy’ applied to photography a lot, but you don’t see it illustrated in art museums.

Morgan and Marvin Smith, Untitled, [Marvin and Morgan Smith and Sarah Lou Harris Carter], 1940 Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library Photograph © Morgan and Marvin Smith.

Austin Hansen, Eartha Kitt Teaching a Dance Class at Harlem YMCA, around 1955 Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library Photograph by Austin Hansen used by permission of Joyce Hansen.

- Called to the Camera: Black American Studio Photographers, 16 September 2022-8 January 2023, New Orleans Museum of Art