Unplaceable Goodness

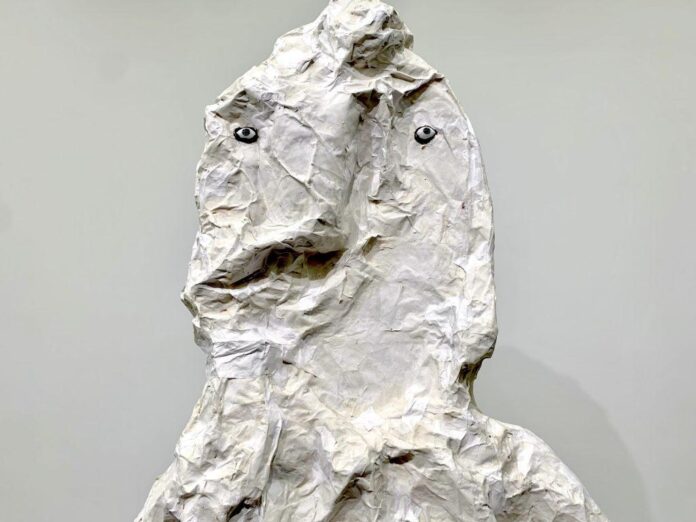

This one-gallery White Columns survey of the recent output of the well-regarded Brooklyn-based sculptor Carol Bruns (b. 1943) makes me think of ghosts. Not just because these sculptures are mainly all in ghostly white, but because ghosts are border characters, between alive and dead. And I take the attempt to achieve a kind of eerie, resonant in-between-ness to be where Bruns’s head is at.

Bruns’s sculptures are in-between in at least three ways. First, in that they are made with found materials, and both show it and don’t show it—you can sense the underlying forms of Styrofoam pieces or pipes found on the street, but Bruns has semi-finished them in white plaster and paint so that they hold together into one, gawky form. Second, they are in-between in that they conjure faces and figures, but always in a not-quite-there way, the final form being half-creaturely, half-object-like. And, finally and most subtly, they are in-between in emotional tone: Are these mask-like reliefs and sculptures spooky or lovable? They exist just at the point where you have to project into them, and they shift states if you stay with them.

There’s a lot of control in holding all these levels of irresolution together at once in an artwork. And if you let yourself steep in Bruns’s show, it’s mind-expanding. (On view through August 26.)

Carol Bruns, (2021), (2022), (2022), and (2022). Photo by Ben Davis.

Carol Bruns, (2022), (2023), and (2021). Photo by Ben Davis.

Carol Bruns, (2023). Photo by Ben Davis.

SCRY Movie (and Paintings)

There’s more unsettled-ness in Rachel Rossin’s “SCRY” (through August 11 at Magenta Plains)—it’s almost like we live in a time where things feel really uneasy and unresolved!

The literal centerpiece of this show is , a LED tondo (part of a project also seen at the Whitney last year and, to crowds, in Berlin). Hung on the ceiling, it radiates a digital glow over everything, playing out a broken, elliptical narrative featuring fragments of an anime girl, animated diagrams, landscapes, and data clusters. The uneasy sense Rossin creates is something like a kind of cyborg consciousness either on the cusp of being born or in the throes of dying.

The suite of paintings hung around the gallery manifest shadowy figures that look alternatively like mechs and angels (or mecha-angels?), based, I gather, on Rossin’s childhood drawings. They capture a similar mood to the LED work, like some kind of sinister memory or liberating epiphany in formation. The miasmic quality of is mirrored in the shifting layers of the marks in the paint, as if the canvas was some kind of visual receiver that was being tuned, and alien transmissions were veering into focus through the static.

The painting-on-canvas and the digital-art parts of the show fit together a little unstably, but I realized that this is also part of the whole idea of “SCRY”: The space between the mediums was also the space between different forms of consciousness; it feels as if a new hybrid art is wrestling to be born, either drawing painting and digital-art together, or thwarted by the air-gap between them.

“Rachel Rossin: SCRY” at Magenta Plains. Photo by Ben Davis.

Rachel Rossin, (2022) at Magenta Plains. Photo by Ben Davis.

Rachel Rossin, (2023). Photo by Ben Davis.

The Weed Pot Avant-Garde

“No secret, just work.” So said the late art ceramicist Doyle Lane (1923–2002) when asked about the secret of his glazes, in an interview that was displayed in a vitrine near the entrance of David Kordansky for this show (which closed, lamentably, before I could get my act together to write this). His “Weed Pots” from the ’60 and ‘70s (no, not that kind of weed; it’s a term for a vessel meant to display a leaf of grass or a sprig of wheat or the like) are individually great. Each is a tiny, complete, confident thing, exploring color or texture.

But—credit where credit is due—the display of 100 Lane-made weed pots at Kordansky (including one that came from the collection of the great painter Charles White) by artist-curator Ricky Swallow was greater than the sum of its parts. It gave a sense, via the clarity of its juxtapositions, of how much delightful variation Lane was able to create within a sober, gimmick-free commitment to craft fundamentals.

Installation view of “Doyle Lane: Weed Pots” at David Kordansky Gallery. Photo by Ben Davis.

Installation view of “Doyle Lane: Weed Pots.” Photo by Ben Davis.

Display of material relating to the life of Doyle Lane at David Kordansky. Photo by Ben Davis.

The “Aesthetic Turn” Gathers Force…

The best thing to read of the last few weeks is definitely “On the Aesthetic Turn” by Anastasia Berg, the scene-setter for ’s summer issue on the question “What Is Beauty For?” (the issue also has a bunch of good essays in it). “The critical tide is turning, once again,” she wrote. In my own review of the mess that is “It’s Pablo-matic” at the Brooklyn Museum, I talked about how we were at an inflection point, where the “moralism” that has been dominant for the better part of a decade in culture writing was increasingly uncool. Berg’s “On the Aesthetic Turn” surveys the different types of positions people are taking as they respond to this shift, while also noting that what this “aesthetic turn” remains somewhat unsettled, more a negative rejection of a dominant style than a new consensus (for this reason, I would call the new style “anti-moralism” rather than an “aesthetic turn,” personally).

Berg’s essay inspires three (very-compressed) thoughts.

“The critics of self-righteousness and trauma mongering are for the most part not calling for a return to the amoral ironism that governed the Nineties and early Aughts—the sensibility that surely gave rise, at least in part, to the overgrowth of didacticism that followed,” Berg wrote. My first thought is that, yes, I think that’s true—but also, in part, there is definitely a contingent that wants a return to amoral ironism. So any argument for an “aesthetic turn” has to be centrally about distinguishing itself, not just from “moralism” but from “bad aestheticism.”

Second, the opposition between “moralism” and “aestheticism” is unstable. As Berg wrote, “In the very way we have posed the question—what is beauty ?—the magazine signals agreement in at least one regard with the moralizers about art: art and beatify must in some sense be salutary.” That is, arguments for the value of aesthetic complexity are often about acknowledging real human complexity, or taking a stand against the instrumentalization of art, or other goals that arrive at a moral or political project by another door. Meanwhile, there’s a coded aesthetic dimension to the “moral” lens on art too: Clear, direct, even overtly didactic art can feel and (aesthetic virtues) against the background of a lot of over-refined, deliberately obscure stuff, where it stands out as different (which, in turn, is part of where ideas about “performative activism” come from—essentially the accusation that a righteous cultural posture is ).

Third (and following from the second), critical insight has to be located at a level above the “moralism” versus “aesthetics” debate. You can’t actually pick a right side in that fight, because the sides have an elastic and overlapping relationship to one another. It is more a matter of local and specific calculations, and how different values are being put to work or combined at a given time and place than it is of right and wrong sides. Critics need specific historical arguments rather than overall theoretical defenses of “the aesthetic” or “activist art.” Framing the matter in terms of sides tends to feed the unhelpful polarization and oscillation between the two, where, for instance, what is really a rejection of sloppy, superficial moralizing becomes conflated with an attack on any moral claims on art, in general.

That’s my three cents on that.

The cover of , issue 30.

Holographic Media and Target Modernism

Two other things to read…

It’s a couple of months old now already, but I just caught this banger of an essay by Caroline Busta and Lil Internet (of New Models fame) on , “Holographic Media.” Looking at the evolution of media—art-based and otherwise—Busta/Internet offer a kind of combined manifesto and prophecy of what comes next, spinning out the implications of the increasing realization that authentic-feeling culture has to exist outside of the big tech platforms if it is to survive.

There’s a lot in their analysis, from their prognosis that “community itself becomes a form of media” to their prediction of the great “Voiding of the Mid”: “Younger generations are already suffering from Mid-exhaustion as endless culture-warring and grandstanding didacticism have made “?using ?your?voice” on social media seem extremely cringe.” It’s all worth chewing on.

Warhol-inspired products on view inside a pop-up Target. (Photo by Mark Von Holden/WireImage)

Finally, speaking of “the Mid”… check out Molly Osberg’s essay from July on art grads putting their skills to use in the alternate-universe art world dedicated to hotel and office art. Among other things, it gives you the telling transition towards “unique” experiences in design, and gives you the category of “Target modern” to think about. Above all, it’s a lot of fun:

These jobs are often to graft together art-world concepts—”modern,” “impressionistic”—and the kinds of adjectives brand managers favor like “gritty” or “airy” or “classic.” In less ambitious settings, the goal is to create something that telegraphs the idea of art without the potentially alienating qualities of an actual piece. Abstract works are popular for this reason: They communicate a vague sense of design history without much in the way of a specific point. Also, the piece has to complement a particular shade of paint.

La Grande Mistake

Just to see how it works, I’ve enabled Google’s A.I.-enabled Search queries—the giant corporation’s latest endeavor to slurp all the value of the internet into its own gullet, and leave as little as possible for anyone else. I find these A.I.-enabled little summaries mainly annoying.

But at least this query for Seurat’s informs me of this huge piece of recent art-market news that I have somehow missed.

Page of Google A.I.-enabled search results for “Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.”

A real loss for Chicago!

And even so, it looks like the Art Institute of Chicago got really ripped off. Because if I try again with Google’s A.I., it tells me that Seurat’s painting has been valued at a whopping $650 million!

Page of Google A.I.-enabled search results for “Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.”

The very-specific number for the almost certainly priceless painting comes from a light-hearted and unscientific thought experiment in a post by Evan Beard, speculating on what the uber-rich might pay for major masterpieces. It illustrates Google A.I.’s habit of yoinking sources and remixing them in its own language—in this case stealing Beard’s fun speculations while mangling the fact that they were either fun or speculative.