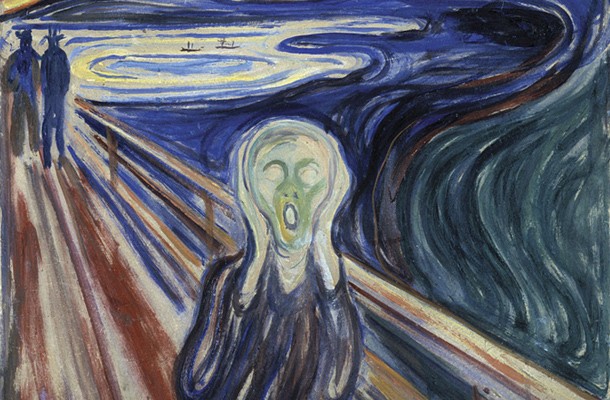

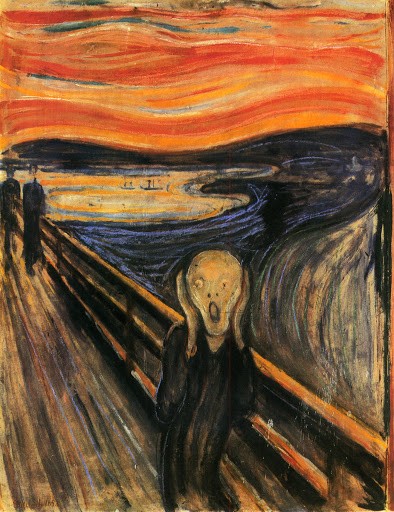

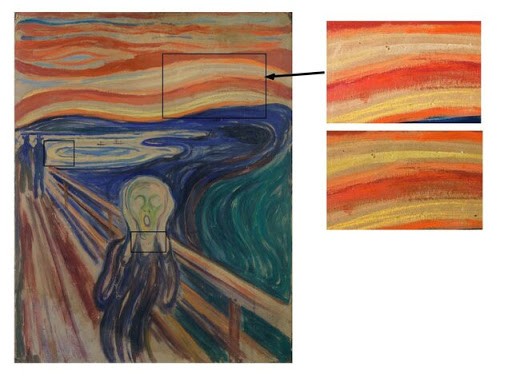

“The Scream” is fading. Scientists study tiny paint samples using advanced technology – X-rays, a laser beam and a powerful electron microscope. They are trying to find out why fragments of the famous painting by Edward Munch, painted in 1910, from bright orange-yellow to white as ivory.

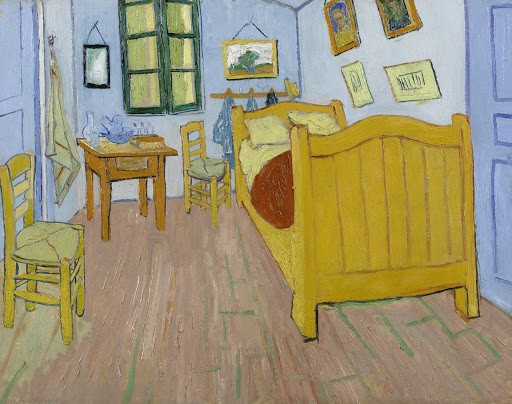

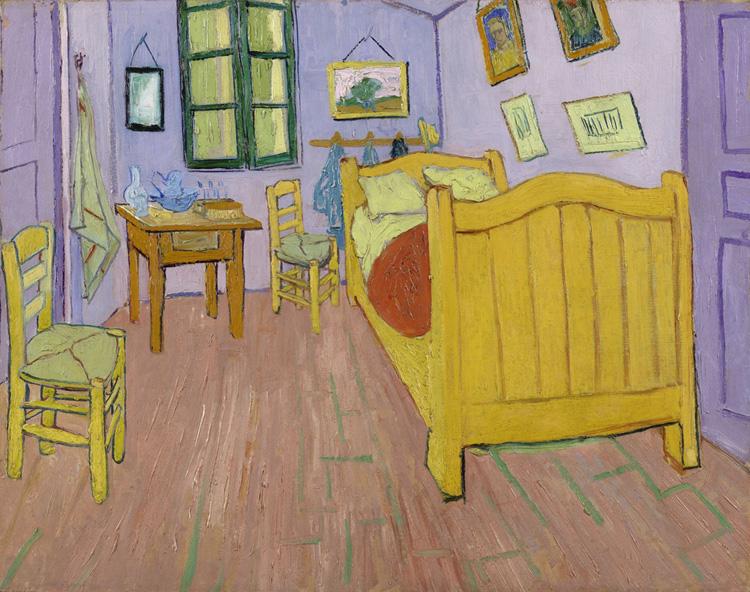

The art world is increasingly turning to the laboratory to find out what is happening to paintings of the late 19th and early 20th century. Yellow on Vincent van Gogh’s canvases has sometimes turned brown, and the purple shades have somewhere “gone” into blue. The Dutchman’s work has been widely studied, but less is known about Munch’s palette. Now scientists, using the latest technology and tools, are making new discoveries.

The team of the Laboratory for Scientific Analysis of Painting in Harlem, studying the “Scream” under the direction of Jennifer Mass, found that under a microscope the surface of the painting resembles a cluster of stalagmites. The nanocrystals growing on the canvas from the Munch Museum are clear evidence of the degradation of the colorful layer near the mouth of the central figure, in the sky and water.

Conservators and researchers at the Munch Museum contacted Dr. Mass because she studied cadmium yellow at the work of Henri Matisse and her laboratory has high-quality scientific instruments. The museum, which is moving into a new building later this year, needs to find out how best to exhibit the painting, taking into account both its conservation and viewing comfort.

The experts have analyzed the materials used by Munch more fully, and this spring they are going to reveal the detailed story of the Scream. Dr. Mass’s team was able to narrow down the selection of paints used by the artist by studying his tubes, about 1400 of which are kept in the Oslo museum. Over time, cadmium yellow sulfide oxidized into two white chemical compounds – cadmium sulfate and cadmium carbonate – under environmental influence.

According to Jennifer Mass, the analysis showed that similar phenomena are observed in 20 percent of impressionist and expressionist paintings created between 1880 and 1920. In fact, these problems can affect all the works whose authors used certain materials.

Colours in paintings of the end of XIX – beginning of XX century fade especially quickly due to changes in the technology of production of paints. Previously, they were made by grinding minerals extracted from the ground or dyes made from plants and insects. The industrial revolution led to the production of synthetic pigments such as cadmium or chrome yellow, which artists mixed with oil and fillers. Artists began experimenting with these synthetic pigments, which sometimes turned out randomly and were not tested for longevity, but were exceptionally bright and formed the shining palettes of Fauvism, postimpressionism and modernism.

At that time, many artists were abandoning traditional painting techniques, says Lena Stringari, chief restorer at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, who studied colour and pigment changes in Van Gogh’s work. “Many masters have worked in the open air and experimented with different theories of colours and colours,” she said. – It was an explosion of colour and a rejection of academism”.

It made the new pigments popular, but they were unpredictable, Dr. Mass stressed. “We can’t say, ‘Oh, it’s a tree, so we know the leaves will be green,'” she explained. – Because Matisse or Munch doesn’t have to, and here we have to rely on science.”

It is impossible to recreate these shades, but science can give us an idea. Cohen Janssens, a chemistry professor at the University of Antwerp who studied pigments by Van Gogh, Matisse and others, said: “The idea is to try to reverse time in some virtual way”.

Conservators will not use new pigments on canvases, but digital reconstructions can show how paintings looked in the past.

Dr. Mass predicts the use of augmented reality in the reconstructions, when it will be possible to bring a smartphone to a painting and see its previous colors.

Physics, organic chemistry and the art world have not always created a triple alliance. “Until recently, art historians were the main ones, they were the ones who insisted on keeping the last word,” explains Kilian Anheuser, chief researcher at Geneva Fine Art Analysis. – And now we have a lot of fake scandals where scientific research is dotted. This changes the situation somewhat.

Research has certainly changed the way art historians view some of Van Gogh’s works. The Artist’s Museum in Amsterdam and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York have in recent years organized exhibitions focusing on the vanishing shades in his paintings. “This is something that we’ve only really realized in the last 10 years. Our thinking has been influenced by research that has focused specifically on technical aspects,” admits Theo Medendorp, art historian and senior research fellow at the Van Gogh Museum.

Interestingly, Van Gogh himself was one of the artists who knew the pitfalls of the new pigments. “I just checked: all the colors that Impressionism made fashionable, unstable – he wrote to his brother Theo in 1888. – There’s no point in using them, time will only soften them more.”

“Paintings fade like flowers,” he remarked later.