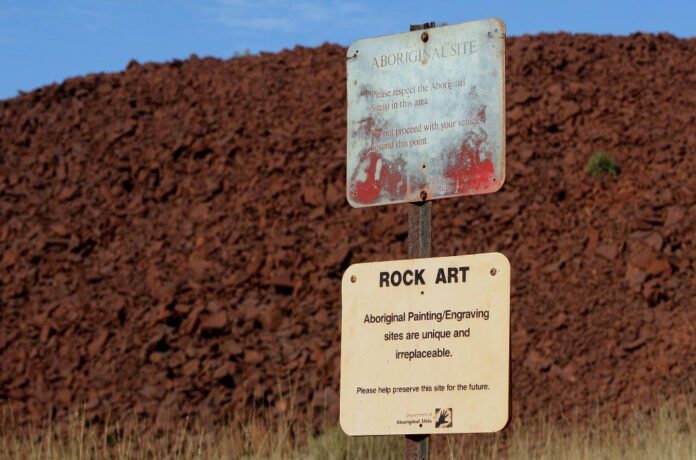

On Australia’s northwestern Burrup Peninsula, the unchecked emissions of the petrochemical industry are not only threatening the region’s natural environment, but also its rich cultural heritage.

The sliver of land is home to Murujuga rock art, a collection of around a million petroglyphs that depict human-like figures, a cornucopia of animals, and several extinct species. It’s also the site of a vast industrial complex including Australia’s largest gas producer, an ammonia plant, and a urea plant that broke ground in late April.

Development in the region began in the 1960s, but was supercharged following the discovery of offshore gas fields which led to the construction of Australia’s largest petrochemical complex and an ongoing battle between conservationists and industrialists. Although previously earmarked projects have been diverted elsewhere in Murujuga National Park, scientists and traditional custodians remain deeply concerned that the current levels of acidic emissions from the petrochemical complex are damaging the etchings made into the reddish brown rocks.

The ancient Aboriginal rock carving known as ‘Climbing Man,’ believed to be thousands of years old, on the Burrup Peninsula, in 2008. Photo: Greg Wood/AFP/Getty Images.

Industrialists operating on the Burrup Peninsula have long denied the impact of emissions on to Murujuga rock art, sometimes using flawed and misleading data to do so, but an investigative paper published by University of Western Australia researchers in in late 2022 makes the case fairly conclusive.

The study, titled “Monitoring Rock Art Decay: Archival Image Analysis of Petroglyphs on Murujuga, Western Australia,” compared 26 petroglyph photographs taken before industrialization and compared them with recent photographs. Half of the petroglyphs showed indications of change and a further two bore signs of substantial damage. With the exception of two petroglyphs, all were located close to the industrial area.

The paper cites three main ways in which industrial activity is damaging the the Murujuga rocks: mechanical removal during land clearances, acidic dust that when mixed with water erodes the rock surface, and the increased occurrences of graffiti, trampling, and theft.

Images comparing 1974 photo with 2021 photo shows damage to fish petroglyph, red arrows show flaking of rock varnish. Photo: Benjamin Smith “Monitoring Rock Art Decay”.

The presence of acidic chemicals emitted by industry is of particular concern to scientists and traditional custodians. The Murujuga rocks have a patina built up by mineralization, which Aboriginal artists scraped and scratched away to reveal the gray rock beneath and create their images. The paper warns that high acid concentrations may completely dissolve the outer veneer of these rocks.

“If emissions are reduced swiftly at Murujuga, the evidence presented in this paper suggests that damage to the rock art may be limited and this extraordinary place can remain largely intact for future generations,” the authors wrote.

The works of Murujuga rock art date back more 40,000 years, but stopped in 1868 when European colonists slaughtered the local Yaburara People in what is known the Flying Foam Massacre.

See more images from the study below.

Images comparing 1973 photo with 2021 photo shows damage to pattern petroglyph. Photo: Benjamin Smith “Monitoring Rock Art Decay.”

Images comparing 1988 photo with 2021 photo shows damage to petroglyph believed to be of lightening. Photo: Benjamin Smith “Monitoring Rock Art Decay.”

Images comparing 1970 photo with 2021 photo shows damage to petroglyph of bird. Photo: Benjamin Smith “Monitoring Rock Art Decay.”

More Trending Stories:

A Sculpture Depicting King Tut as a Black Man Is Sparking International Outrage