If you had dined at the Grand Pacific Hotel in Chicago in 1880 for the Annual Game Dinner, you might have had a hard time choosing among the 50 species offered. If Ham of Black Bear didn’t tempt you, maybe Ragout of Squirrel à la Francaise was your jam. One would expect to be charmed by some anachronistic dishes (and rock bottom prices) at an exhibition of vintage menus. But there is much more than kitsch value to “A Century of Dining Out: The American Story in Menus, 1841–1941” and plenty of subtext between the appetizer and dessert sections.

The show, which opened in April at The Groiler Club in Manhattan and runs until July 29, lives up to its name. Free of charge and open to non-members, it idiosyncratically and chronologically tells the story of American gastronomy, and the young country itself—in menus. These include menus from restaurants, banquets, soup kitchens, private yachts, and even houses of ill repute.

An installation view of “A Century of Dining Out: The American Story in Menus, 1841-1941” in the ground floor gallery. Courtesy of The Groiler Club.

“It’s like a 15-degree slice of history,” said collector Henry Voigt, who adroitly curated the show and wrote the accompanying catalogue. “You’re looking from a different perspective. It’s not just what people were eating, but what they were doing, with whom they were doing it, and what they valued. It’s a mirror of society. Yes, it runs along class lines, but it represents all classes in various ways. They’re minor historic documents that reflect everyday life.”

On the Great Western Railway (ca. 1881), left, the fixed price for breakfast was 75 cents. The beverage list offered over three dozen Champagnes, clarets, and ales. The gilt-edge menu at right came from a social event catered by Louis Sherry (1855–1926) in New York City in 1884, a few months after he opened his confectionery and catering business, serving New York society’s highest echelons. Courtesy of the Henry Voigt Collection of American Menus.

He continued, “I reflect on not only just the upper classes, but women’s history, African American history, and what’s dubbed economic precarity, meaning people who have been pushed from a livable life by war and financial crisis. These menus are very rare. Who saved a menu from a soup kitchen, saying, ‘I wanna remember this evening for the rest of my life?’”

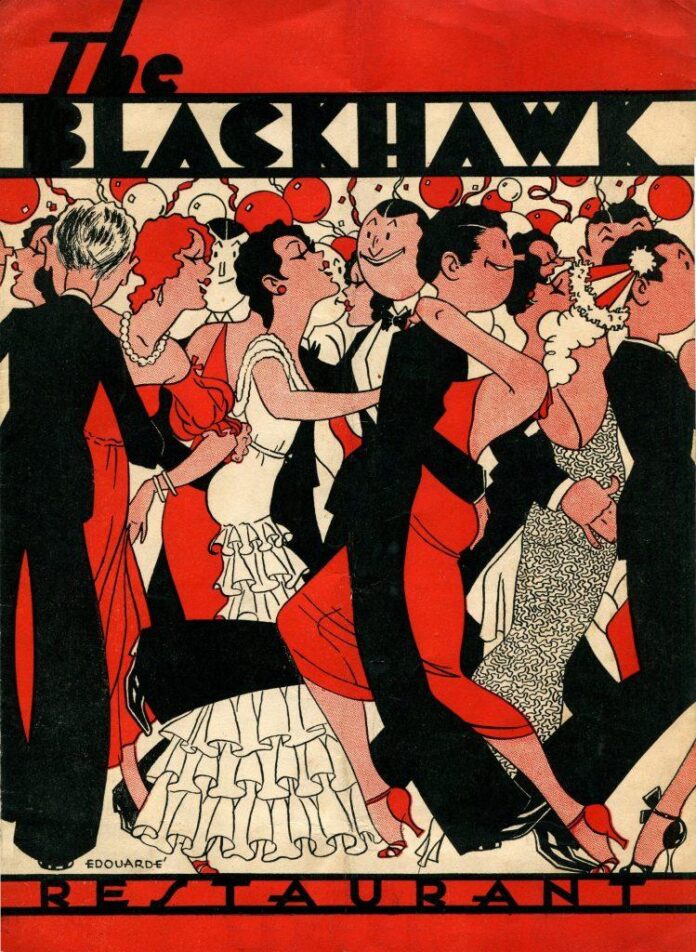

Major swaths of the American story are reflected in these menus. The show is divided into sections such as “The Great War and Onset of Prohibition,” “King Cotton and the Telegraph,” “Echoes of the Jazz Age,” and “The Great Depression and Recovery.”

Mark Twain’s 70th birthday party was national news. Delmonico’s (New York City, 1905) bill of fare is illustrated with comic sketches by cartoonist Leon Barritt (1852–1938) depicting the guest of honor in successive stages of his career. The dinner was hosted by George Harvey, the owner and editor of which published a special supplement with photographs of the 170 guests. Courtesy of the Henry Voigt Collection of American Menus.

Shortly after he had completed the show’s installation, Voigt—in a tie, blazer, and loafers—gave me a run-through of some of the 224 menus he’d selected for the exhibition. “Oh, this one makes me tear up,” he said. “A couple of them here make me lose it.” He pointed out an Emancipation Banquet menu from an African-American social club honoring Sojourner Truth. Nearby was the menu for Lincoln’s second inaugural ball; guests could munch on delicacies such as terrapin and tongue en gelée.

Voigt noted two other menus, saying, “These are the only two menus I know of from southern states under Confederate control, one from Lanier House in Macon, Georgia, in 1862 and the American Hotel in Richmond in 1864, which perished in a fire the following year during the fall of Richmond. There was a scarcity of food in the Confederacy.”

This menu is remarkably sparse. In the accompanying exhibition notes, Voigt wrote, “The lack of shipments from outside the region also caused the cuisine to be markedly local in character. The ham-and-greens dish was made with poke sallet weed, a poisonous wild plant popular in Appalachia and the South. The leaves must be boiled in water three times to make them safe to eat, even in the early spring when its toxins are at the lowest levels.”

The Palmer House (Chicago, 1886) opened on September 26, 1871, only 13 days before it burned to the ground in the Great Fire. The second Palmer House advertised itself as “thoroughly fire proof.” It hosted such famous guests as actress Sarah Bernhardt; writers Mark Twain and Oscar Wilde; and Presidents James Garfield, Ulysses S. Grant, and Grover Cleveland. Courtesy of the Henry Voigt Collection of American Menus.

An Ellis Island menu, typewritten on onion skin paper, is particularly moving. It offered boiled rice and milk, and bread and butter, to newly arrived children. “When poor immigrants arrived in the 19th century, they came in steerage and they were in a state of shock,” Voigt explained. “Read about the number of children that died on the island. So, the practice began to give them milk and bread.”

“Immigrants thought that America was welcoming them with food,” he added. “The food was paid for by the shipping lines, but they thought America was. And 50, 60, 70 years later, they had warm feelings. No, they’d never seen white bread before, but they knew they would be okay because food is symbolic. We welcomed them symbolically.”

The Gem (New Orleans, ca. 1913), left, operated in an old mansion on Royal Street from 1847 to 1919. The menu for Maxim’s (New York City, 1917), right, was designed in the Louis XIV style. Future silent-screen idol Rudolph Valentino began his career as a busboy at Murray’s and later landed at Maxim’s as a “taxi dancer,” a paid dance partner for lone women. Courtesy of the Henry Voigt Collection of American Menus.

The advent of modernism in the 1920s marked an invigorating aesthetic shift, but it would be short-lived given the simultaneous rise of Prohibition. “There was nothing cool about Prohibition,” Voigt said. “It was a disaster. People didn’t care about food anymore. The good restaurants were all closed. Speakeasies didn’t care about food. People no longer drank wine; they drank booze. Society collapsed and food did too, from an haute cuisine point of view.”

Voigt paused and continued thoughtfully, “Prohibition was repealed in December of 1933, but it took about 50 years to get over it. When do you think we got back on our feet gastronomically? The 1980s!”

The cuisine at the finer American hotels, such as the Winthrop House (Boston, 1852), might be described as “Frenchified English cooking,” as one British visitor put it, with an emphasis on wild game. The focal point of this dinner at its restaurant, Hasty Pudding Club, was provided by the seven varieties of game birds. Courtesy of the Henry Voigt Collection of American Menus.

Before embarking on menus, Voigt and his wife collected 17th- and 18th-century Dutch art. “It was a reflection of everyday life,” he said. “I’ve always been interested in everyday life. We were also interested in food and wine. Also interested in how food affects culture and societal patterns.” He sold off the paintings, keeping only prints and drawings. Menus became a focus when he retired at 60 as a senior executive at Dupont in the mid-1990s.

“It’s not just the art element,” Voigt said of his attraction to the milieu and explained what he looks for. “What’s the language of the menu? Who’s the intended audience? Is there evidence of race, gender, or class? All menus are seen through the prism of class. What about the typography? What about the graphic design? Who owned this menu? Why did they save it? Who was the printer? Who was the lithographer? Visual appeal is wonderful, but there’s a series of questions around a menu’s significance.”

The Cathay Tea Garden (Philadelphia, 1926), left, had a large dance floor and hosted a regular radio program. Four pages are divided between “American dishes” and “Chinese dishes.” After more than 50 years, the Cathay Tea Garden closed in 1973. The Fountain Room at the Hotel Pennsylvania (New York City, 1924), right, was the largest in the world when it opened on January 25, 1919, a few days before the 18th Amendment was ratified. When Prohibition went into effect, some hotel bars were turned into soda fountains. Courtesy of the Henry Voigt Collection of American Menus.

Voigt has now amassed about 12,000 menus and stores them in his home in Delaware. His wife doesn’t partake in his collecting. “I’m very interested in history, food, and wine,” he said. “And everyday life. It wasn’t an expensive hobby like owning a sailboat. It was an ignored field. It wasn’t like collecting art, where you needed to be a multi-billionaire to go to an auction and buy one thing. This was something that I could do.”

It’s not surprising that Voigt isn’t thrilled with today’s QR code dining culture, but he’s not trapped in the past. “I don’t pine for the old days when I look at the menus,” he said. “The old days are not as great as we think they were. Life is better now than it was then. Certainly for more people.”

Steinberg’s Dairy Restaurant (New York City, 1938) streamlined its Art Déco interior, mirrored in the cover design of this menu that offered Eastern European Jewish foods including salmon, borscht, vegetarian (mock) chopped liver, chopped herring, cabbage soup, potato latkes, cheese blintzes, and kreplach. Opened in 1931, Steinberg’s was one of several dairy restaurants on the Upper West Side. Courtesy of the Henry Voigt Collection of American Menus.