Four new exhibitions of light art this autumn—two in historic churches in London; two in locations purpose-built for immersive experiences and 21st-century technology—demonstrate both the blessing and the challenge that artists find in working with light using the latest technology, including algorithms written to manage ever more powerful, and efficiently packaged, arrays of light-emitting diodes (LEDs).

It is a combination that has allowed creatives to play with light—composing it with code—over the last two decades, with the related challenge that they may suffer the creative paralysis of (too much) choice. (The technology has also allowed the development of mega screens to show immersive light and video pieces, culminating with the recent opening of the 360ft-tall Sphere in Las Vegas.)

London Design Festival and Bloomberg Philanthropies commissioned the church pieces from two artists, Moritz Waldemeyer and Pablo Valbuena, to mark the 300th anniversary of the death of Christopher Wren—a giant of British architecture, master of light and mathematics, and creator of London landmarks including St Paul’s Cathedral and the Royal Hospital Chelsea.

On 27 September, Random International, a European collaborative studio founded in 2005 by Hannes Koch and Florian Ortkrass, opened a nine-month show of its immersive interactive work at the Nxt Museum in Amsterdam.

On 12 October, United Visual Artists (UVA), a London-based collective founded in 2003 by the British artist Matt Clark, opens the largest survey to date of its work, with eight site-specific immersive sound-and-light pieces at 180 Studios in central London, who are curating the show in collaboration with the cultural strategist Julia Kaganskiy.

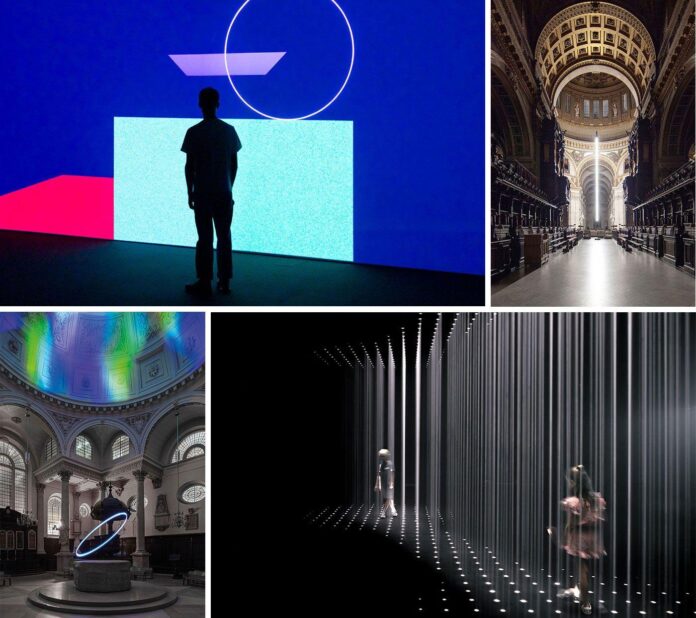

Moritz Waldemeyer’s light installation Halo, at St Stephen Walbrook, London © Ed Reeve

Waldemeyer, the London-based German artist and designer, devised Halo for St Stephen Walbrook (1672-79), the City of London church where Wren built the first dome in any British building. Waldemeyer’s piece is made up of a 20m-long pendulum, with an LED light source that moves up and down the cord from which it hangs in frequency with the rotation of its brass weight, sweeping low and meditatively over the rim of Henry Moore’s massive 1972 marble altar. Waldemeyer made use of a pre-packed tube of LEDs known as COB (chip on board) which he finds performs with a smooth, fluorescent effect similar to that of neon.

Pablo Valbuena’s Aura, hanging in the transept of St Paul’s Cathedral, London © Ed Reeve

Valbuena, the France-based, Spanish installation and light artist, created Aura for St Paul’s Cathedral (completed in 1710). Aura is suspended by a cord from the oculus at the centre of the building’s inner dome. The light sources, a series of hundreds of custom-made LEDs, are hung on a pencil-thin aluminium frame, 20m tall. The light piece in Aura is activated by sound, using an algorithm devised by Valbuena’s team. The audio is captured by the cathedral’s microphones, for spoken words, while additional devices are used to capture the singing of the choir or placed in the organ pipes.

As the sound varies in pitch, volume and intensity, so the patterns of light generated by Aura change. The higher the pitch the higher the light glows on the artwork’s frame. The greater the volume or intensity, the brighter and denser the light that Aura emits.

All the artists concerned have emerged on the light art scene in the past 20 years—paying homage variously to their living predecessors James Turrell and Robert Irwin and to the late Dan Flavin and Ingo Maurer—during the period in which LEDs have gone from being an electronic component for industry, to the equivalent of another group of pixels, in programmable digital art.

“I started out in the early 2000s,” Waldemeyer says. “The time that LEDs started this incredible journey from being an indicator light on your stereo to be an actual means of illumination.” An LED is an electronic component that works well, he explains, with a programmable controller: “[This] gives rise to infinite amounts of creativity.”

Musica Universalis (2023), by United Visual Artists, whose survey exhibition at 180 Studios opens on 12 October

For UVA the creative realisation came when Clark saw that with LEDs “you are sculpting a mass of tiny highly efficient light bulbs”. For its new show, Polyphony, UVA is showing a mixture of new commissions and a site-specific recreation of Our Time, a piece previously created for 180 Studios which examines our perception of time, with a score by the late electronic musician Mira Calix. For Clark, Synchronicity at 180 Studios is an opportunity to show “new interpretations of ongoing lines of inquiry. When working with specialists you get to dive into their world of expertise and knowledge, and we really wanted to revisit some of the highlights of our journey. But we did not want just to represent works that people had seen before, but to create new works.”

Clark describes one of the most complex pieces in the show, Polyphony—a work created with the soundscape ecologist Bernie Krause composed of 150 LED light columns that react to the rhythms of the sonic world of a natural habitat captured by Krause—as an “almost holographic floating volume of light. Like sitting inside a spectrogram [the tool that depicts sound in waveforms]”.

Using custom software, UVA deconstructed and reconstructed Krause’s work as a study in light of the rhythmical aspects of the sonic world found in a natural habitat. While working with Krause in Sonoma, California, Clark looked at Krause’s recordings and noticed a “very strange mark” on the spectrogram which turned out to be an aeroplane flying over, “silencing the natrual habitat”. Every installation is rooted in an idea, Clark says. “The tech supports the narrative and not the other way.”

“For me, the use of tech is interesting,” Valbuena says. “Am I allowed to speak from a more contemporary mode to questions that have been asked throughout human history?… I try to use the simplest way to do it with the available technology,” he says.

Interacting with a spatial intelligence: Living Room—Variation II (2023), Random International’s new version of a 2022 piece for its show at the Nxt Museum, Amsterdam Riccardo de Vecchi

Koch says that, at Nxt Museum, Random is recreating Living Room, a piece using light and fog launched at Art Basel in Miami Beach 2022, where users feel they are interacting with a spatial intelligence. To achieve this, Random’s R&D team developed narrow-beamed light sources using custom lenses strong enough to reach the ground from four metres up, combined with powerful Lidar sensors—as used in self-driving cars—to feed into an algorithmic environment that sometimes responds to a person’s presence and sometimes not.

Koch and Ortkrass have been “looking for past decade and a half at how our environment has developed in an increasingly sentient and increasingly responsive manner”, with smartphones and the growing use of sensors in daily life. Light, Koch says, is “a great medium to explore how that has happened”.

New technology “does not replace strong ideation, strong… intention,” Koch says. “What we are trying to do is to simplify things.” Random’s dramaturge, Héloïse Reynolds, has a counter to the fear of “feature creep” that comes when a medium reaches a state of creative facility such as has happened with programmable LEDs. It is an answer that might apply to all the artists under consideration. Her colleagues, Reynolds says, will “always find the hardest way if it means they are [as artists] doing the right thing ”.